공공예술, 도시의 결을 잇는 언어

Public Art, a Language that Weaves the Texture of the City

Boiling Pot

Boiling Pot에는 기아 디자인 크리에이티브 철학 ‘오퍼짓 유나이티드(Opposites United)’가 뜻하는 상반된 개념의 창의적 융합을 바탕으로 정립된 문화적 특징들이 용광로 속 한 데 어우러져 녹아든 것과 같은, 정제되고 순도 높은 문화의 스토리를 다루고 있습니다. ‘공간’, ‘환경’, ‘예술’ 등의 사회·문화적 현상을 OU 관점에서 조명하여, 크리에이티브 철학을 새롭게 통찰할 수 있습니다.

Boiling Pot

Boiling Pot features stories of pure, refined cultures born from the creative fusion of opposites, embodying the essence of Kia Design’s creative philosophy, ‘Opposites United’. The social and cultural projects are examined from this perspective and offers readers new creative insights.

청계천의 물길을 따라 걷다 보면, 도시가 예술을 품는 방식이 얼마나 달라졌는지를 느낄 수 있습니다. 복원 20주년을 맞은 청계천은 이제 단순한 하천이 아니라, 예술이 도시의 리듬 속에 스며드는 장소가 되었습니다. 물결 위로 펼쳐진 빛과 설치, 그리고 사람들의 시선이 어우러지는 그 장면은 서울의 공공예술을 넘어, 오늘날 한국의 도시들이 예술을 받아들이는 방식을 보여주는 하나의 풍경입니다.

이제 예술은 서울만의 이야기가 아닙니다. 부산의 해안 산책로와 광주의 아시아문화전당, 제주와 강릉의 도시재생 구역까지 한국 곳곳의 도시들은 각자의 역사와 환경, 주민의 삶을 바탕으로 서로 다른 형태의 공공예술을 실험하고 있습니다. 한국의 공공예술은 늘 시대의 표정을 닮아 있습니다. 도시의 얼굴을 바꾸던 1980년대의 기념비적 조형물에서, 주민이 직접 참여하던 2000년대의 마을 프로젝트, 그리고 기술과 환경, 공동체가 함께 호흡하는 오늘의 예술로 이어져 왔습니다. 조형과 장식의 영역에 머물던 예술은 이제 도시를 작동시키는 시스템으로 자리 잡았고, 사람과 제도, 공간과 데이터가 얽혀 새로운 관계망을 만들어가고 있습니다.

예술과 도시는 더 이상 분리된 영역이 아닙니다. 도시의 기능과 예술의 감성이 충돌하고 융합하는 지점에서 우리는 삶의 질서를 새롭게 바라보고 그 틈에서 예상치 못한 아름다움을 발견합니다. 기아 디자인 철학 Opposites United가 말하듯 서로 다른 가치가 만나는 곳에서 진화는 시작됩니다. 《기아 디자인 매거진》 vol.16 ‘Boiling Pot’은 이 철학의 세 가지 문화적 특징인 문화의 선구자, 창의적 모험가, 지치지 않는 혁신가가 도시와 사회의 층위에서 서로를 가열하며 하나의 에너지로 응축되는 순간을 기록합니다. 이번 호는 이러한 관점에서 공공예술을 통해 우리가 사는 도시가 어떤 방식으로 움직이는지 살펴보고 그 속에서 예술과 디자인이 서로를 비추며 끓어오르는 힘으로 새로운 도시의 풍경을 어떻게 만들어내는지 새롭게 읽어내고자 합니다.As you walk alongside the Cheonggyecheon stream, you begin to sense the profound change in the city’s approach to art. Now marking its 20th year since restoration, Cheonggyecheon is no longer just a waterway. It has become a place where art flows naturally within the rhythm of the city. The lights and installations glimmering over the water, interwoven with the gaze of passersby, form a scene that reflects not only the evolution of Seoul’s public art but also how contemporary Korean cities are learning to live with art.

Art today is no longer a story unique to Seoul. From Busan’s seaside promenades and Gwangju’s Asia Culture Center to the urban regeneration districts of Jeju and Gangneung, cities across Korea are experimenting with public art in ways shaped by their histories, environments, and communities. Korean public art has always mirrored the spirit of its time, from the monumental sculptures that reshaped cityscapes in the 1980s to the community-driven village projects of the 2000s, and now to works that breathe together with technology, ecology, and the collective. Once confined to form and ornament, art has evolved into a living system that operates within the city, connecting people, institutions, spaces, and data into new relational networks.

Art and the city are no longer separate realms. At the point where civic function meets artistic sensibility, we discover new orders of life and unexpected beauty. Art becomes another language that moves the city, while the city, through that language, learns to expand its own senses Kia Design Magazine Vol.16, ‘Boiling Pot’, is inspired by this very energy of transformation. Amid the simmering tempo of the urban present, art and design reflect one another, inviting us to reconsider how the cities we inhabit truly move.

Author’s Note

왜 유럽만 가면 그렇게 걷고 싶을까.’

2년 전 방문했던 스위스 취리히와 영국 런던의 길거리가 떠오릅니다. 두 나라는 이미 아트로 유명한 곳이며, 지금의 ‘Art Basel’, ‘Frieze’라는 큰 아트 페어를 탄생시킨 나라의 주요 도시입니다. 또한 두 도시는 금융, 경제, 문화의 중심지이자, 공공예술이 도시 곳곳에 스며든 공간이기도 합니다.

그 거리에서 만난 공공예술은 사람들의 일상 속 접점을 통해 소통하며, 공공의 예술성을 띠고 시민들에게 경험과 실천을 아우르는 개념으로 자리매김하고 있습니다. 조형물, 가로수, 주변의 벤치, 어린이 놀이터의 시설, 지역의 표지판과 안내판까지 어느 하나에서도 눈을 뗄 수 없었습니다. 그때 ‘공공예술’이란 작은 안내판에서부터 우리가 인식하기 쉬운 기념비나 상징적인 조형물, 미디어 파사드까지를 모두 포함하는 것이라는 생각이 들었습니다. 공공예술은 이처럼 일상 속에서 크고 작게 공공의 허브를 구축하며, 지역사회의 특색에 맞게 작용하여 그 지역만의 커뮤니티를 형성하게 합니다. 그렇다면 도시적 관점에서 공공예술을 바라보았을 때, 한국의 ‘공공예술’은 어떠한 모습으로 나타났고 발전해 왔으며, 어떻게 서울이라는 도시의 이야기를 이어 나가고 있을까요. 《기아 디자인 매거진》 vol.16 ‘Boiling Pot’에서는 바로 그 질문에 대한 탐구를 시작합니다. 서울이라는 거대 도시의 일상 속에서 ‘공공예술’이 어떤 방식으로 시민과 관계 맺고, 또 도시의 정체성을 새롭게 만들어가는지를 조명합니다.

Author’s Note

Why is it that we feel the urge to walk endlessly when we are in Europe? I recall the streets of Zurich and London, which I visited two years ago. Both are cities long celebrated for their art and are home to two of the world’s most influential art fairs, Art Basel and Frieze. They are also global centers of finance, economy, and culture, where public art permeates the cityscape at every turn.

The public art I encountered there communicated through points of contact in everyday life. It carried a shared sense of artistry that invited citizens to experience and participate. From sculptures and street trees to benches, playgrounds, and even signs and wayfinding systems, everything seemed part of one coherent aesthetic. At that moment, I realized that public art encompasses much more than monuments or symbolic sculptures. It extends to even the smallest signpost or a flicker of digital light.

In this way, public art builds networks of connection throughout daily life, reflecting the character of each region and nurturing its own community identity. From an urban perspective, how has Korean public art taken shape, evolved, and contributed to the ongoing story of Seoul?

Kia Design Magazine Vol. 16, ‘Boiling Pot’, begins its exploration with this very question. Within the daily rhythm of Seoul, the magazine examines how public art engages with its citizens and how it continues to redefine the city’s identity.

- 1980–1990년대

도시가 예술을 입다, 공공예술의 첫 장 - 2000–2010년대

공공예술, 도시와 사람을 잇다 - 2010년대 중반

도시의 숨결을 품은 공공예술 - 오늘날의 공공예술

‘보이는 것’을 넘어 도시를 움직이다

- 1980s–1990s

When the City Wore Art: The First Chapter of Public Art - 2000s–2010s

Public Art Connecting Cities and People - Mid-2010s

Public Art Breathing with the City - Public Art Today

Beyond What Is Seen, Moving the City

Chapter 01.

1980–1990년대

도시가 예술을 입다, 공공예술의 첫 장

Chapter 01.

1980s–1990s

When the City Wore Art: The First Chapter of Public Art

한국에서 공공예술이 본격적으로 주목받기 시작한 시기는 1988년 ‘서울올림픽’ 무렵입니다. ‘문화올림픽’을 표방하며 서울을 국제도시로 발전시키려는 움직임 속에서 다양한 도시 프로젝트가 추진되었습니다. 환경 정비와 교통 인프라 확충, 조경 사업 등 국가 단위의 도시 환경 개선이 빠르게 이루어졌고, 도시 곳곳이 새롭게 단장되었습니다.

이 시기 조각공원 사업이 문화정책의 일환으로 활발히 진행되면서, 서울의 미관과 이미지를 바꾸는 상징적인 전환점이 마련되었습니다. 1988년 올림픽공원에 조성된 조각공원은 그 시대의 열망과 상징을 고스란히 담은 대표적인 사례로 꼽힙니다. 대형 조형물이 즐비한 풍경은 ‘보이는 예술’이 도시의 얼굴을 새롭게 정의하던 시대의 단면이기도 합니다.

Public art in Korea began to draw real attention around 1988, during the period of the Seoul Olympic Games. Under the banner of a “Cultural Olympics,” the city embarked on numerous urban projects aimed at transforming Seoul into an international metropolis. National-level initiatives such as environmental restoration, transportation infrastructure, and large-scale landscaping were carried out at remarkable speed, giving the city a renewed appearance.

During this time, the sculpture park movement flourished as part of broader cultural policy, marking a symbolic turning point that reshaped Seoul’s aesthetic and identity. The sculpture park created in Olympic Park in 1988 remains one of the most representative examples of that era’s ambition and spirit. The sight of monumental sculptures scattered across the landscape captured the essence of an age when “visible art” came to define the very face of the city.

1980년대 후반 ‘아시안게임’과 ‘서울올림픽’을 전후로 다양한 공공예술 심포지엄과 국제초대전이 열리며, 공공예술은 도시정책의 중요한 축으로 자리 잡았습니다. 1972년 제정된 ‘문화예술진흥법’에 ‘건축물 미술장식’ 조항이 신설되면서 일정 규모 이상의 건물에는 예술작품을 설치해야 하는 ‘퍼센트 포 아트(Percent for Art)’ 제도가 도입되었습니다. 미술관과 화랑의 경계를 넘어, 예술이 일상 속으로 스며드는 첫걸음이었습니다.

이 제도는 비인간적인 도시 환경을 문화적으로 치유하고, 사람과 공간이 공존하는 도시를 만들기 위한 시도로 평가받습니다. 그러나 시행 과정에서는 작가 선정의 불투명성, 공간과의 맥락 부족, 이해관계의 충돌 등 여러 한계도 드러났습니다. 도시 미관 개선과 예술의 공공성 확대라는 성과를 남겼지만, 작품의 지속가능성과 의미에 대한 성찰은 부족했습니다.

그럼에도 이 시기의 공공예술은 한국 도시가 예술과 만나는 첫 실험의 장이었습니다. 도시가 예술을 통해 자신을 표현하기 시작한 순간이자, 예술이 도시의 일부로 살아 움직이기 시작한 시기였습니다. 이후 이러한 흐름은 제도와 철학의 전환을 거쳐, 더 깊고 참여적인 형태로 확장되어 나갑니다.

By the late 1980s when the Asian Games and the Seoul Olympics were taking place, numerous public art symposiums and international exhibitions were held, establishing public art as a central element of urban policy. With the amendment of the Culture and Arts Promotion Act in 1972 to include a “building art decoration” clause, Korea adopted a percent for art system that required large-scale buildings to incorporate artworks. This marked the first step in bringing art beyond museums and galleries and into the flow of everyday life.

The policy was viewed as an effort to culturally heal the impersonal urban environment and to create cities where people and spaces could coexist harmoniously. Yet, the implementation revealed several limitations, including opaque artist selection processes, weak contextual integration with architectural spaces, and conflicts of interest. While the initiative succeeded in improving the urban landscape and expanding the public presence of art, it often lacked deeper reflection on the sustainability and meaning of the works themselves.

Even so, this period served as the first experimental stage in Korea’s encounter between art and the city. It was the moment when the city began to express itself through art, and when art began to live and move as part of the city. In the years that followed, this current evolved through shifts in policy and philosophy, developing into more participatory and community-centered forms of public art.

Scene 1.

기념비가 된 공원, 그 빛과 그림자

올림픽조각공원의 양면

서울 송파구 올림픽공원에 자리한 조각공원은 1988년 서울올림픽과 함께 탄생한 상징적인 공간입니다. ‘문화올림픽’이라는 비전 아래, 스포츠와 예술이 공존하는 도시의 풍경을 구현하기 위해 조성되었습니다. 이곳은 단순한 전시장이 아니라 도시와 자연, 그리고 인간의 감각이 함께 호흡하는 살아 있는 예술의 장으로 자리 잡았습니다.

공원에는 국내외 작가의 조각 200여 점이 설치되어 있습니다. 작품들은 1980년대 세계 조각의 흐름을 반영하며, 기하학적 형태와 단순화된 인체, 재료의 물성을 중심으로 한 다양한 조형 언어를 보여줍니다. 잔디와 하늘, 바람 사이에서 작품은 주변 풍경과 섞이며 스스로의 표정을 바꿉니다.

방글라데시 작가 하미두자만 칸 Hamiduzzaman Khan의 ‘Steps’(1988)은 구리 재질의 4m 구조물로, 인간의 자유와 진보를 상징합니다. 위로 향하는 리듬과 확장의 형태가 조각적 긴장감을 만들어내며, 표면에 반사되는 햇빛은 시간의 흐름에 따라 또 하나의 작품처럼 변주됩니다. 프랑스 작가 미셸 가이 미셸 Michel Guy Michel의 ‘Dialogue’는 두 개의 곡선이 서로를 마주보는 형상으로, 인간 관계의 긴장과 조화를 시각화합니다. 관람자가 그 사이를 걸어 들어가면 작품의 일부가 되며, ‘공간 속의 대화’라는 주제를 직접 체험하게 됩니다. 한국 작가 김정원의 ‘꿈꾸는 새’는 흰 대리석으로 만들어진 유려한 곡선의 조형물입니다. 하늘로 날아오르려는 새의 형상은 인간의 희망과 생명력을 상징하며, 바람과 햇살, 그림자의 움직임 속에서 고요히 변화합니다. 작품은 시간의 결을 따라 살아 있는 유기체처럼 호흡합니다.

이곳에서 예술은 감상의 대상이 아니라 체험의 풍경으로 존재합니다. 작품과 사람, 빛과 그림자, 계절의 변화가 함께 엮이며 하나의 장면을 만듭니다. 관람자는 작품을 ‘보는’ 것이 아니라 그 속을 ‘걷는’ 존재가 됩니다. 조각이 도시의 배경이 아닌 일상의 일부가 되는 순간, 예술은 공간과 삶의 경계를 허물며 또 하나의 공공성을 만들어냅니다.

물론 한계도 있습니다. 조성 당시 국제 작가 초청 중심으로 진행되면서 일부 작품은 장소적 맥락과의 연결이 부족했습니다. 관리와 보존의 문제 또한 꾸준히 제기되어 왔습니다. 그러나 여전히 이 공간이 가진 예술적 가치는 유효합니다. 도심 속에서 조각이 바람과 빛, 사람의 발걸음과 함께 살아 숨 쉬는 장소라는 점에서, 올림픽공원 조각공원은 ‘예술이 도시를 어떻게 품을 수 있는가’라는 질문에 가장 아름다운 답을 들려줍니다.

Scene 1.

A Park of Monuments: Its Light and Shadow

The Two Faces of the Olympic Sculpture Park

Located in Songpa-gu, Seoul, the Olympic Sculpture Park is a symbolic site born alongside the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Under the vision of a “Cultural Olympics,” it was created to embody a cityscape where sports and art coexist. More than a simple exhibition venue, the park has become a living field of art where the city, nature, and human sensibility breathe together.

Around 200 sculptures by Korean and international artists are installed throughout the park. These works reflect the global sculptural trends of the 1980s, expressing diverse formal languages through geometric structures, simplified human figures, and an exploration of materiality. Amid the grass, sky, and wind, each piece merges with its surroundings, changing its expression with light and time.

Steps (1988) by Bangladeshi artist Hamiduzzaman Khan is a four-meter copper structure symbolizing human freedom and progress. Its upward rhythm and expanding form create sculptural tension, while the light reflected on its surface transforms with the passing hours. French artist Michel Guy Michel’s Dialogue depicts two facing curves that visualize both harmony and tension in human relationships. As visitors walk between them, they become part of the artwork itself, experiencing the “dialogue within space.” Korean sculptor Kim Jung-won’s Dreaming Bird, carved from white marble, presents a graceful form of ascent. The image of a bird poised to take flight embodies human hope and vitality, changing quietly with the movements of light, wind, and shadow. Each piece breathes like a living organism that moves with time.

Here, art exists not merely as an object of appreciation but as a landscape of experience. Works, people, light, shadow, and the changing seasons weave together to create a single scene. Visitors do not simply look at the sculptures; they walk through them. At the moment when sculpture becomes part of everyday life rather than a backdrop to the city, art dissolves the boundary between space and living, creating a new sense of public intimacy.

Of course, there are limitations. At the time of its creation, the project largely focused on inviting international artists, and some works lacked contextual connection with their surroundings. Issues of maintenance and preservation have also persisted. Yet the artistic significance of this space remains undeniable. As a place where sculpture continues to breathe with the wind, light, and footsteps of people in the heart of the city, the Olympic Sculpture Park offers one of the most eloquent answers to the question: How can art embrace the city?

Chapter 02.

2000–2010년대

공공예술, 도시와 사람을 잇다

Chapter 02.

2000s–2010s

Public Art Connecting Cities and People

‘공공예술’은 2000년대에 접어들며 그 흐름이 눈에 띄게 달라집니다. 조각이나 구조물처럼 형태로 존재하던 예술이 ‘과정’과 ‘관계’에 주목하기 시작했습니다. 이 시기부터 예술은 지역성과 참여, 사회적 메시지를 품으며, 도시와 사람 사이의 새로운 관계를 설계하는 언어로 확장되었습니다.

2005년 시작된 안양공공예술프로젝트(Anyang Public Art Project, APAP)는 그 전환의 방향을 가장 뚜렷하게 보여주는 사례였습니다.

“공공예술은 단순한 조형물이 아니라 도시와 시민의 관계를 설계하는 과정이다.”

이 선언은 예술이 더 이상 관람의 대상이 아니라, 도시의 구조와 일상의 방식을 바꾸는 힘이 될 수 있음을 보여주었습니다. 당시 낙후된 안양유원지는 예술가와 건축가, 디자이너, 시민이 함께 만들어낸 ‘예술적 도시공원’으로 다시 태어났습니다. 공공예술이 공간을 꾸미는 장식이 아니라, 도시가 스스로를 새롭게 정의하는 과정이 된 것입니다.

Public art in Korea underwent a striking transformation in the 2000s. What had once existed as tangible forms such as sculptures, monuments, or structures began to focus instead on process and relationship. Art started to embrace locality, participation, and social meaning, evolving into a language that redefined the connections between cities and their inhabitants.

Launched in 2005, the Anyang Public Art Project (APAP) became the clearest embodiment of this shift. Its declaration, “Public art is not a static object but a process of designing relationships between the city and its citizens,” redefined the essence of what public art could be. It suggested that art could move beyond being an object of appreciation to become an active force capable of reshaping the structures and rhythms of everyday urban life.

At the time, the aging Anyang Amusement Park was transformed into an “artistic city park,” created through collaboration among artists, architects, designers, and local residents. The project demonstrated that public art could no longer be confined to decoration or visual enhancement. It had become a process through which a city reimagines and reconstructs its own identity.

이 흐름은 2006년 ‘도시와 미술 프로젝트’와 2009년 ‘마을미술프로젝트’로 이어지며 전국으로 확산되었습니다.

도시환경 개선을 목표로 출발했지만, 곧 주민이 직접 참여하는 사회적 예술로 방향이 바뀌었습니다.

낡은 골목이 예술을 통해 다시 태어나고, 벽화와 마을길이 공동체의 기억을 이어주는 공간이 되었습니다. 이 과정에서 예술은 지역의 정체성을 되살리고, 잊혀진 관계를 회복하는 매개로 기능했습니다. 특히 2006년 ‘도시와 미술 프로젝트’ 이전인 2005년에 시작된 ‘안양공공예술프로젝트(Anyang Public Art Project, APAP)’는 한국 공공예술의 전환점을 보여주는 대표적인 사례입니다.

This movement continued to expand nationwide through the “City and Art Project” in 2006 and the “Village Art Project” in 2009. Initially launched to improve the urban environment, these projects soon evolved into forms of social art that encouraged direct participation from local residents. Old alleyways were reborn through art, and murals and village paths became spaces that preserved the collective memory of their communities.

Through these processes, art served as a medium to revive local identity and restore forgotten relationships. Among these initiatives, the Anyang Public Art Project (APAP), which began in 2005 and preceded the City and Art Project, stands as a defining example of Korea’s turning point in public art, illustrating how art can reshape the dialogue between people and the city.

물론 그 길이 언제나 순탄했던 것은 아닙니다. 관 주도의 사업 구조, 주민 참여의 한계, 설치 이후의 유지관리 문제 등 현실적인 벽도 존재했습니다. 그러나 이러한 시행착오들은 공공예술이 무엇을 위해, 누구와 함께 존재해야 하는가에 대한 중요한 질문을 남겼습니다. 결국 2000년대의 공공예술은 ‘기념비의 시대’를 지나 ‘과정의 시대’로 나아갔습니다. 예술은 더 이상 높은 단상 위에서 도시를 내려다보지 않습니다. 사람들의 일상 속에서, 함께 걷고 말하고 만들어가는 시간 속에서 스스로의 의미를 찾아갑니다. 그 변화는 예술이 도시를 치유하고, 사회의 결을 잇는 가장 인간적인 방식이 될 수 있음을 보여주었습니다.

Of course, it was not always plain sailing. There were real challenges, including government-driven project structures, limited community participation, and difficulties in maintaining works after installation. Yet these trials raised essential questions about the purpose of public art and the people it should serve.

Ultimately, the public art of the 2000s moved beyond the era of monuments into an era of process. Art no longer stood on a pedestal overlooking the city. It began to find meaning within everyday life, walking, speaking, and creating alongside people. This transformation showed that art could become one of the most human ways to heal the city and weave together the texture of society.

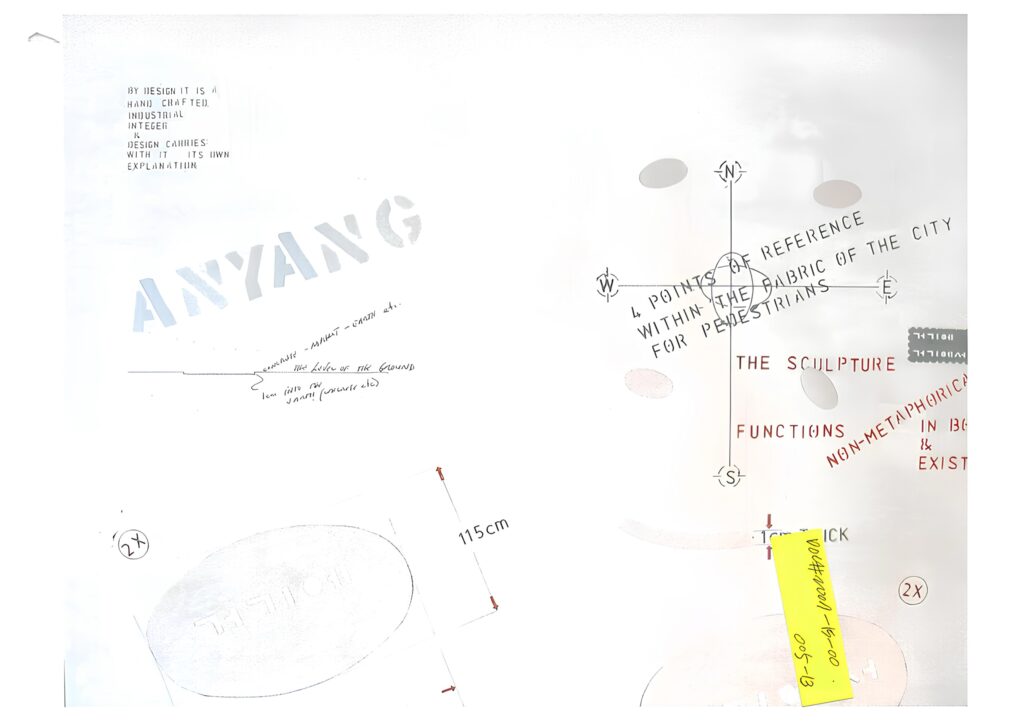

Scene 2.

도시와 예술이 만나는 법,

APAP의 실험

안양공공예술프로젝트(Anyang Public Art Project, APAP)는 도시 전체를 하나의 미술관으로 확장하려는 실험에서 출발했습니다. 2005년 시작된 이 프로젝트는 “공공예술은 단순한 조형물이 아니라 도시와 시민의 관계를 설계하는 과정이다”라는 새로운 인식을 제시하며, 한국 공공미술의 방향을 바꾼 중요한 계기가 되었습니다.

당시 낙후되어 있던 안양유원지는 세계 각국의 예술가와 건축가들이 참여하면서 ‘예술적 도시공원’으로 재탄생했습니다. 포르투갈의 건축가 알바로 시자Álvaro Siza가 설계한 Anyang Pavilion은 그 상징적인 출발점이었습니다. 이 건축물은 단순한 전시관이 아니라, 시민이 내부를 거닐며 도시 풍경을 새롭게 인식하게 하는 ‘공공의 공간’으로 설계되었습니다. 도미니크 페로Dominique Perrault의 Anyang Pavilion 2는 금속 재질의 구조물 속에 하늘과 빛을 반사시켜, 도심 속에서 ‘열린 건축’의 개념을 구현했습니다.

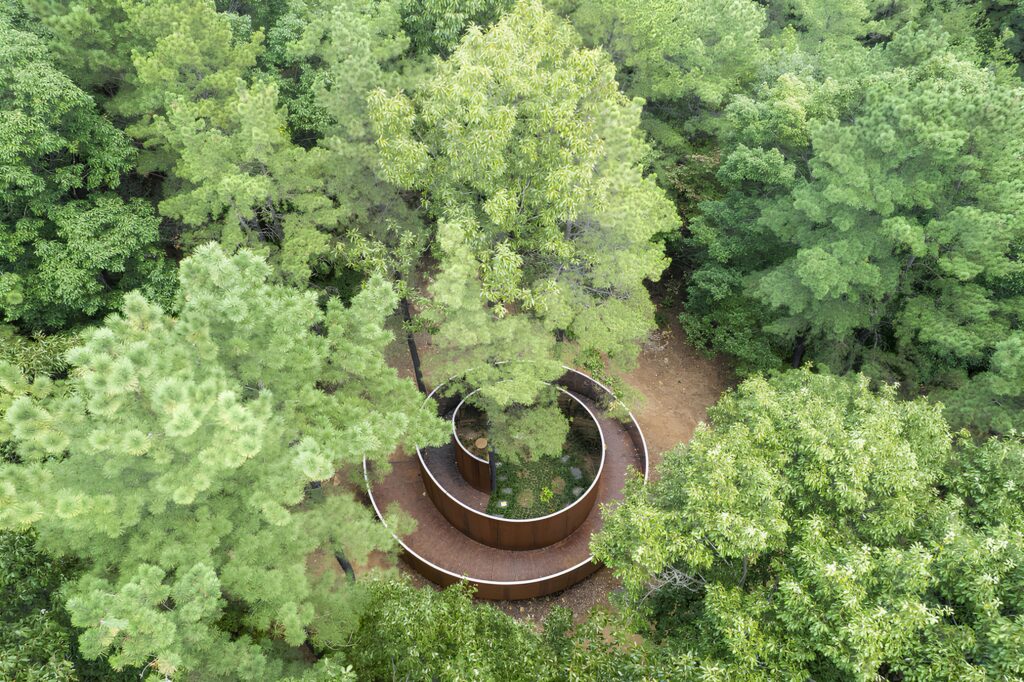

프로젝트는 매회 다른 주제로 확장되었습니다. 2016년에는 아르헨티나 작가 아드리안 비야 로하스Adrián Villar Rojas의 Brick Farm이 등장했습니다. 도심 속 버려진 공간을 흙과 식물로 채우며, 조각과 생태, 도시 재생의 경계를 허문 이 작품은 ‘도시 속 생명의 순환’을 시각적으로 보여주었습니다. 최근에는 네덜란드 건축 그룹 넥스트 아키텍츠NEXT Architects의 Secret Forest Pavilion이 숲과 건축, 인간의 감각을 연결하는 형태로 설치되어, 방문자가 숲과 도시의 경계를 오가며 자연과 공간의 관계를 새롭게 체험할 수 있도록 했습니다.

이처럼 APAP는 건축, 조각, 사운드, 미디어, 사회학 등이 융합된 복합 예술로 발전해왔습니다. 작품이 단지 설치되어 있는 ‘오브제’가 아니라, 그 공간에서 시민이 어떤 경험을 하고 어떻게 관계를 맺는지가 핵심이 되었습니다. 예술은 도시의 일상 속으로 들어왔고, 시민의 동선과 감정의 리듬 속에서 살아 움직이기 시작했습니다.

그러나 이 프로젝트가 남긴 과제도 분명합니다. 국제 작가 중심의 기획으로 인해 작품이 지역 맥락과 어긋나거나, 주민과의 공감대 형성이 부족했다는 지적이 있었습니다. 또한 대형 설치물 중심의 프로젝트가 시간이 지나면서 관리의 어려움과 의미의 퇴색이라는 문제를 겪기도 했습니다. 그럼에도 안양공공예술프로젝트는 한국 공공예술의 지형을 바꾼 실험으로 평가됩니다. 조형물의 시대를 지나 과정의 예술로 확장하며, 예술이 도시와 사람을 연결하는 새로운 언어가 될 수 있음을 보여주었기 때문입니다.

Scene 2.

How Cities and Art Meet,

The Experiment of APAP

The Anyang Public Art Project (APAP) began as an experiment to expand an entire city into an open-air museum. Launched in 2005, it introduced a new understanding of public art: “Public art is not a static object but a process of designing relationships between the city and its citizens.” This marked a turning point in the direction of Korean public art.

The formerly declining Anyang Amusement Park was reborn as an “artistic city park” through the participation of artists and architects from around the world. Portuguese architect Álvaro Siza’s Anyang Pavilion marked this symbolic beginning. Designed as more than an exhibition hall, it invited citizens to walk inside and perceive the cityscape anew, functioning as a “public space” for reflection and movement. French architect Dominique Perrault’s Anyang Pavilion 2 followed, using metallic structures that captured and reflected the sky and light to embody the concept of “open architecture” within the city.

The project continued to expand, with each edition featuring new themes. In 2016, Argentine artist Adrián Villar Rojas presented Brick Farm, transforming an abandoned urban site into a living installation of soil and plants. Blurring the boundaries between sculpture, ecology, and urban renewal, the work offered a striking visual metaphor for the cycle of life within the city. More recently, the Dutch architectural group NEXT Architects introduced the Secret Forest Pavilion, a structure connecting forest, architecture, and human perception. Visitors moving through it experience a shifting boundary between city and nature, engaging with the space in new sensory ways.

Through such works, APAP has evolved into a multidimensional art platform that integrates architecture, sculpture, sound, media, and sociology. The focus lies not on the artwork as an object but on the experience—how citizens interact with the space and what kind of relationships they build within it. Art has entered the flow of everyday urban life, moving in rhythm with people’s paths, emotions, and time.

Yet the project also revealed challenges. Some works, created under an internationally focused curatorial structure, lacked local context or community resonance. Large-scale installations faced difficulties in maintenance and loss of meaning over time. Still, APAP remains one of the most influential experiments in the landscape of Korean public art. By moving beyond the age of monuments and into the age of processes, it demonstrated that art can become a new language connecting cities and people.

Chapter 03.

2010년대 중반

도시의 숨결을 품은 공공예술

Chapter 03.

Mid-2010s

Public Art Breathing with the City

2010년대 중반 이후, 공공예술은 다시 한번 변곡점을 맞이합니다. 참여형 프로젝트를 넘어 기술의 발달과 미디어의 진화, 커뮤니티의 활성화가 맞물리며 예술의 경험 자체가 달라지기 시작했습니다. 기술과 예술의 경계가 허물어지면서 ‘공공예술’은 이제 ‘미디어+아트’, ‘퍼포먼스+아트’, ‘온라인+아트’ 등 복합적이고 다층적인 형태로 확장됩니다.

이 시기의 공공예술은 복합성을 핵심으로 삼으며 형태적 실험을 이어갑니다. DDP, 경복궁 등 주요 건축물의 입면을 활용한 미디어아트 전시는 공공예술의 가능성을 도시의 규모로 확장시키며, 도시 이미지를 새롭게 쓰는 대형 프로젝트로 발전합니다. 이 과정에서 건축물은 단순한 배경이 아니라 예술의 캔버스이자 관람의 무대가 됩니다. DDP에서는 매년 ‘Seoul Light DDP’를 개최해 건물의 내외부를 빛과 영상으로 채우며, 도시의 얼굴을 새롭게 비춥니다.

Since the mid-2010s, public art in Korea has once again reached a point of transformation. Beyond participatory projects, advances in technology, the evolution of media, and the activation of local communities began to change the very experience of art itself. As the boundaries between technology and art grew increasingly fluid, public art expanded into complex and multi-layered forms such as media + art, performance + art, and online + art.

Public art of this era took complexity as its core and continued to experiment with form. Media-art exhibitions using the façades of major architectural landmarks such as DDP and Gyeongbokgung Palace broadened the scale of public art to that of the city itself, evolving into large-scale projects that rewrote the visual identity of urban spaces. In this process, architecture became not merely a backdrop but both a canvas for art and a stage for spectatorship.

At DDP, the recurring event “Seoul Light DDP” fills the building’s interior and exterior with light and moving images each year, presenting a renewed face of the city and showing how art can illuminate the rhythm of urban life.

또한 각 지자체는 지역의 정체성과 환경에 어울리는 다양한 형태의 공공예술을 시도합니다. 미디어 파사드, 대형 퍼포먼스, 온·오프라인이 연계된 인터랙티브 프로젝트 등 기술 기반의 예술이 활발히 펼쳐집니다. 디지털 기술을 이용한 실시간 반응형 설치나 데이터 시각화 작업은 관람자와 작품의 경계를 허물고, 예술을 살아 있는 시스템으로 변화시킵니다.

이제 예술은 감상의 대상이 아니라 시민이 함께 참여하고 체험하는 장으로 확장됩니다. 이러한 흐름은 도시재생의 담론과 맞물리며 ‘공공예술의 지속가능성’이라는 새로운 화두를 만들어냅니다. 낙후된 지역을 예술로 되살리는 프로젝트가 전국으로 확산되고, 도시 공간 개선을 목표로 한 공공디자인과 결합하면서 예술은 도시의 운영체제 속으로 들어옵니다. ‘예술로 지역을 살린다’는 구호 아래, 예술인 마을과 창작 스튜디오, 문화거점 공간이 조성되고, 일부 지자체는 예술을 기반으로 한 도시 운영 모델을 실험하고 있습니다.

이 변화는 공공예술이 더 이상 도시의 외형을 장식하는 수단이 아니라, 사회적 가치와 도시 전략이 만나는 접점으로 자리 잡았음을 보여줍니다. 기술과 예술, 시민의 참여가 얽히며 만들어낸 새로운 공공예술의 풍경 속에서 예술은 다시 도시를 호흡하게 합니다. 빛과 화면, 사람과 데이터가 하나의 장면 안에서 만나며, 예술은 이제 도시의 언어로 말하고 있습니다.

Local governments across Korea have also begun exploring new forms of public art suited to their unique identities and environments. Media façades, large-scale performances, and interactive projects that link online and offline spaces have become increasingly common, showcasing the vitality of technology-based art. Real-time responsive installations and data visualization works using digital technology blur the line between viewer and artwork, transforming art into a living, dynamic system.

Art is no longer a passive object of appreciation but an open field for participation and shared experience. This shift aligns with the broader discourse of urban regeneration, introducing a new agenda of “sustainability in public art.” Projects that revitalize declining neighborhoods through art have spread nationwide, combining with public design initiatives aimed at improving urban spaces. Under the vision of “reviving communities through art,” artist villages, creative studios, and cultural hubs have been established, while some municipalities have begun experimenting with city management models rooted in art and culture.

This transformation shows that public art has evolved beyond decorating the city’s exterior. It now occupies the intersection where social values meet urban strategy. Within this new landscape where technology, art, and civic participation are deeply intertwined, art once again allows the city to breathe. Light, screens, people, and data come together in a single shared scene, and art now speaks in the language of the city itself.

Scene 3.

DDP의 빛, 경복궁의 그림자

도시가 예술이 되는 밤

기술의 발전과 미디어의 확장은 공공예술의 얼굴을 완전히 바꾸어 놓았습니다. 예술은 더 이상 조각이나 벽화로 머물지 않습니다. 도시의 건축물과 거리, 사람의 일상 속으로 스며들며, 기술과 예술이 만나는 경계에서 새로운 감각을 만들어냅니다. ‘미디어+아트’, ‘퍼포먼스+아트’, ‘온라인+아트’로 진화한 공공예술은 도시를 하나의 거대한 플랫폼이자 살아 있는 무대로 변화시켰습니다.

그 중심에는 동대문디자인플라자(DDP)가 있습니다. 곡선으로 흐르는 금속 외피는 밤이 되면 수천 개의 빛으로 깨어나며 예술과 기술이 만나는 실험의 장이 됩니다. 2025년 가을 열린 ‘서울라이트 DDP’에서는 건물 전체가 하나의 스크린으로 변했습니다. 파사드 위로 빔프로젝션과 레이저, 디지털 설치 작품이 펼쳐졌고, 그 빛의 파동이 서울의 밤을 감싸 안았습니다. 도시의 건축이 예술의 캔버스가 되고, 시민의 시선이 그 위를 스치며 하나의 공연이 완성되는 순간이었습니다.

DDP 내부의 미디어 아트 갤러리는 디지털 아트가 일상과 맞닿는 공간입니다. 시민이 직접 체험하는 인터랙티브 작품을 통해 예술은 감상의 대상에서 살아 있는 시스템으로 작동합니다. 이러한 시도는 공공예술이 ‘보는 예술’에서 ‘참여하는 언어’로 변화하고 있음을 보여줍니다. 경복궁 일대에서 진행된 ‘미디어 아트 가든 프로젝트’ 역시 인상적인 실험입니다. 자연과 빛, 생명을 주제로 한 설치 작품이 고궁의 정적인 풍경과 어우러지며 시간의 결이 중첩된 새로운 감각의 공간을 만들어냅니다.

과거와 현재, 정적과 동적이 한 장면 안에서 공존하는 순간, 공공예술은 도시와 시대를 잇는 언어가 됩니다.

이러한 변화는 도시재생의 흐름과 결합하며 ‘공공예술의 지속가능성’이라는 새로운 개념으로 확장되었습니다.

예술은 낙후된 지역을 되살리고, 도시의 생활 구조 속에서 새로운 가치를 만들어내는 힘이 되었습니다.

전국 곳곳에 창작 스튜디오와 예술인 마을, 문화거점 공간이 생겨나며, 예술은 도시의 맥박 속으로 들어와 다시 호흡하기 시작했습니다. 이 흐름 속에서 기아의 미디어아트는 기술과 철학, 그리고 도시의 감성을 하나로 묶은 상징적 장면으로 남습니다.

2022년 서울라이트 DDP에서 공개된 기아의 작품은 브랜드의 디자인 철학 ‘오퍼짓 유나이티드(Opposites United)’를 미디어아트로 구현했습니다. 서로 다른 성질이 만나 새로운 아름다움을 창조한다는 철학 아래, ‘Technology for Life’, ‘Bold for Nature’, ‘Joy for Reason’, ‘Power to Progress’, ‘Tension for Serenity’의 다섯 가지 원칙이 DDP 외벽 위에서 빛과 음향으로 펼쳐졌습니다.

작품은 ‘우주적 삶’을 주제로, 마음속 작은 우주에서 피어나는 감정과 통찰을 빛으로 표현하며 미래 도시와 예술의 공존을 상징했습니다. 이처럼 2010년대 중반 이후의 공공예술은 단순한 조형물의 시대를 넘어, 기술과 시민, 환경이 맞물리는 복합적 현상으로 진화하고 있습니다. 도시의 벽은 캔버스가 되고, 광장은 스크린이 되며, 시민의 움직임은 예술의 일부가 됩니다. 공공예술은 그렇게 우리가 사는 도시를 하나의 살아 있는 예술로 만들어가고 있습니다.

Scene 3.

Light at DDP, Shadows of Gyeongbokgung

The Night When the City Becomes Art

Advances in technology and the expansion of media have completely transformed the face of public art. Art no longer remains as sculpture or mural; it now seeps into the city’s architecture, streets, and daily life, creating new sensory experiences at the boundary where technology and art converge. Evolving into forms such as media + art, performance + art, and online + art, public art has turned the city into a vast platform and a living stage.

At the heart of this transformation stands the Dongdaemun Design Plaza (DDP). Its flowing metallic curves awaken at night in thousands of lights, becoming a site for experimentation where art and technology meet. During Seoul Light DDP 2025 (Autumn Edition), the entire building became a screen. Beam projections, lasers, and digital installations filled the façade, enveloping Seoul’s night in waves of light. It was a moment when architecture became a canvas, citizens’ gazes became brushstrokes, and a collective performance came to life.

Inside, DDP’s media art gallery connects digital art to everyday experience. Interactive installations allow visitors to engage directly, transforming art from an object of observation into a living system. These experiments show how public art is evolving from something to see into a language to participate in.

The Media Art Garden Project around Gyeongbokgung Palace offers another memorable example. Installations themed around nature, light, and life blend with the palace’s tranquil scenery, layering the dimensions of time to create a space of overlapping sensations. In that coexistence of past and present, stillness and motion, public art becomes a language linking city and era.

This evolution has merged with urban regeneration, expanding into a new concept of sustainability in public art. Art has become a force that revitalizes neglected neighborhoods and generates new value within the structure of urban life. Across the country, creative studios, artist villages, and cultural hubs have emerged, allowing art to enter the city’s bloodstream and breathe once again.

Within this flow, Kia’s media art remains a symbolic moment where technology, philosophy, and the city’s emotional pulse come together. Presented at Seoul Light DDP 2022, Kia’s installation visualized the brand’s design philosophy, Opposites United, through light and sound. Based on five principles—Technology for Life, Bold for Nature, Joy for Reason, Power to Progress, and Tension for Serenity—the work explored the harmony of contrasting forces, expressing the coexistence of future cities and art through the theme of “Cosmic Life.”

This new era of public art, emerging since the mid-2010s, transcends the age of static forms. It represents a complex convergence of technology, citizens, and the environment. City walls become canvases, plazas become screens, and the movements of people become part of the artwork. In this way, public art continues to transform the city we live in into a living work of art.

Chapter 04.

오늘날의 공공예술

‘보이는 것’을 넘어 도시를 움직이다

Chapter 04.

Public Art Today

Beyond What Is Seen, Moving the City

오늘날의 공공예술은 ‘보이는 것’을 넘어 ‘작동하는 예술’로 진화하고 있습니다. 예술은 더 이상 하나의 조형물이나 시각적 장식으로 머물지 않습니다. 도시의 흐름 속에서 사회적 기능과 제도, 기술적 운영 구조를 함께 설계하며, 하나의 시스템으로 작동하는 존재가 되었습니다. 이제 공공예술은 지역 공동체와 협의하고, 데이터를 읽으며, 제도와 재정을 설계하고, 사회적 갈등을 조정하는 복합적 기술이자 도시 운영의 일부로 기능합니다.

기술의 발전과 환경적 요구가 맞물리면서, 예술은 점점 더 구체적인 현실과 만납니다. 지역사회 협의, 데이터 기반 기획, 지속가능성을 고려한 설계가 예술의 새로운 기본 언어가 되었습니다.

서울 성북구의 ‘도시데이터 기반 예술지도 프로젝트’는 도시의 공공데이터를 시각화해 예술로 재해석한 장면을 보여줍니다. 세종시의 ‘스마트시티 아트 프로젝트’는 도시 인프라와 미디어아트를 결합해 시민과 도시가 실시간으로 소통하는 방식을 실험하고 있습니다. 부산의 ‘디지털 파사드 아트’는 건축물의 외피를 미디어 캔버스로 전환해 도시 경관을 변화시키는 동시에 에너지 절감과 환경 인식을 함께 구현합니다.

이러한 시도는 예술이 도시의 문제를 함께 고민하고, 현실을 움직이는 또 다른 시스템이 될 수 있음을 보여줍니다. 이제 예술가는 단순한 창작자가 아니라 도시의 이미지를 설계하고, 사람과 사람 사이의 관계를 조율하는 조정자가 되었습니다. 기업과 지자체, 국가 또한 예술을 사회적 혁신의 도구로 인식하며 공공예술을 새로운 실험의 장으로 확장하고 있습니다. 기술과 시민 참여가 결합된 융합적 시도 속에서 예술은 도시를 치유하고, 관계를 다시 잇는 언어로 살아납니다. 오늘의 공공예술은 ‘누가, 어떻게 함께 만드는가’라는 질문 속에 존재합니다. 특정 공간에 고정된 작품이 아니라, 협력의 언어로 이어지는 사회적 행동이며, 도시 문제를 풀기 위한 대화의 장이자 시민의 생각이 교차하는 열린 플랫폼입니다. ‘보이는 예술’에서 ‘작동하는 예술’로의 이 전환은, 결국 예술이 도시의 구조와 사람의 관계를 새롭게 설계하는 과정입니다. 예술은 더 이상 도시를 장식하지 않습니다. 그 자체로 도시를 움직이는 또 하나의 생명, 또 하나의 호흡이 되고 있습니다.

Since the mid-2010s, public art in Korea has evolved into what might be called “operating art.” It no longer exists simply as an object or visual ornament. Within the flows of the city, art now engages social functions, institutions, and technical systems, acting as one of the components that make the city itself work.

Today’s public art consults with local communities, reads data, designs institutional and financial structures, and mediates social conflict. With technological advancement and growing environmental awareness, art meets increasingly tangible realities. Community consultation, data-driven planning, and sustainability-oriented design have become the new common language of art.

Projects such as Seongbuk-gu’s Urban Data-Based Art Map visualize public data as artistic expression, reinterpreting the city through information. The Smart City Art Project in Sejong connects media art with urban infrastructure to enable real-time interaction between citizens and the city. In Busan, the Digital Façade Art project turns architectural surfaces into media canvases, reshaping the skyline while promoting energy efficiency and environmental awareness.

These initiatives show how art can engage directly with urban issues and operate as another civic system. Artists today are not merely creators but coordinators who design urban imagery and mediate relationships between people. Companies, municipalities, and national agencies increasingly recognize art as a tool for social innovation, expanding public art into a new arena of experimentation.

In these hybrid practices, where technology and civic participation intertwine, art becomes a living language that heals cities and reconnects communities. Contemporary public art exists in the question of who creates, and how we create together. It is no longer confined to fixed spaces but functions as a collaborative language, a form of social action, and a platform for dialogue and shared imagination.

The shift from visible art to operating art ultimately represents a new process of designing how cities and people relate to one another. Art no longer decorates the city; it becomes part of its life and motion another form of breath that keeps the city alive.

박명선

세종대학교 건축학과를 졸업한 그는 ‘공간을 만드는 일’을 삶의 중심에 두고 있다. 건축을 통해 배운 구조적 사고와 공간 감각을 토대로, 시각디자인과 출판, 매거진 기획까지 그 영역을 확장해왔다. 현재 신파출판의 설립자이자 I.M STUDIO 디자이너, 그리고 〈sophia.sel.mag〉의 디렉터로 활동하며, 공간과 시각, 텍스트가 교차하는 지점을 탐구하고 있다.

Park

Myung-sun

A graduate of the Department of Architecture at Sejong University, Park Myung-sun places the act of creating spaces at the center of her life and work. Building on the structural thinking and spatial sensitivity she gained through architecture, she has expanded her practice into visual design, publishing, and magazine curation.

She is the founder of Shinpa Publishing, a designer at I.M STUDIO, and the director of 〈sophia.sel.mag〉, where she explores the intersection of space, image, and text seeking new forms of dialogue between structure and sensibility.

Epilogue

어느 동네의 비어 있던 공터가 계절마다 쓰임을 바꾸며 ‘동네 허브’로 거듭납니다. 지역 작가들의 작품이 걸리고, 가로는 그 지역의 정체성에 맞게 조성됩니다. 그곳에서 아이들은 꿈을 공유하고 어른들은 커뮤니티를 형성합니다. 주말마다 미디어 전시, 공연, 영화 상영이 이어집니다. 이러한 관계를 설계하는 것이 바로 ‘공공예술’입니다. 앞으로의 ‘공공예술’은 지속가능한 시스템으로 발전하며, 운영 기반의 예술 생태계를 구축해야 합니다. 도시의 구조 속에서 예술은 일회성 이벤트가 아닌 도시의 ‘운영체제’로서 존재해야 합니다. 이제 공공예술이 향해야 할 길은 분명합니다. 눈에 보이는 결과보다 작동하는 과정으로, 일회적인 사건보다 지속 가능한 시스템으로, 개별 창작자의 세계보다 함께 살아가는 공동체의 이야기로 나아가야 합니다. 그것은 단순한 조형물에 머물지 않고, 여러 관계망 속에서 도시와 사람이 예술로 교류할 수 있는 작동 메커니즘을 품는 것을 의미합니다. 이제 ‘공공예술’은 사회 데이터를 기반으로 인간과 자연, 기술과 제도를 융합한 ‘작동하는 상상력의 장치’로 거듭나야 합니다.

Epilogue

An empty lot in a neighborhood transforms with each season, taking on new roles and becoming a true community hub. Local artists exhibit their works there, and the streetscape evolves to reflect the identity of the area. Children share their dreams, while adults build relationships and networks. On weekends, media exhibitions, performances, and film screenings fill the space with life. Designing these relationships is what public art is truly about.

The future of public art lies in developing sustainable systems and building an ecosystem that supports continuous artistic operation. Within the structure of the city, art should no longer exist as a one-time event but as part of the city’s operating system.

The direction of public art is now clear. It must move from visible outcomes to functioning processes, from temporary events to sustainable systems, and from the individual artist’s world to the shared stories of communities living together. This means going beyond the realm of sculpture or installation to create mechanisms through which people and cities can interact through art.

Public art must now become a device of operative imagination, a living system built on social data that integrates humans and nature, technology and institutions. In this way, art can evolve into a continuously functioning language that keeps the city and its people connected.