미술관 속 비밀의 문이 열릴 때, 수장고를 마주하는 새로운 방식

Behind the Museum’s Hidden Doors, A New Way of Seeing the Storage Unfolds

Boiling Pot

Boiling Pot에는 기아 디자인 크리에이티브 철학 ‘오퍼짓 유나이티드(Opposites United)’가 뜻하는 상반된 개념의 창의적 융합을 바탕으로 정립된 문화적 특징들이 용광로 속 한 데 어우러져 녹아든 것과 같은, 정제되고 순도 높은 문화의 스토리를 다루고 있습니다. ‘공간’, ‘환경’, ‘예술’ 등의 사회·문화적 현상을 OU 관점에서 조명하여, 크리에이티브 철학을 새롭게 통찰할 수 있습니다.

Boiling Pot

Boiling Pot features stories of pure, refined cultures born from the creative fusion of opposites, embodying the essence of Kia Design’s creative philosophy, ‘Opposites United’. The social and cultural projects are examined from this perspective and offers readers new creative insights.

Editor’s Note

미술관은 우리에게 조용하게 말을 걸어옵니다. 벽에 걸린 작품 한 점, 좌대 위에 놓인 조각 하나에 커다란 세계가 응축되어 있습니다. 하지만 우리가 전시장에서 마주하는 작품은 미술관이 보유한 방대한 소장품 중 일부에 불과합니다. 대부분의 작품은 공개되지 않은 조용한 수장고 속에 머물고 있습니다. 수장고는 단지 보관의 장소를 넘어, 예술 작품이 가진 시간과 가치가 축적된 공간이기도 합니다. 그러나 최근, 이 보이지 않던 공간의 문이 서서히 열리고 있습니다. 수장고를 개방하고, 디지털 아카이빙을 통해 소장자료를 공유하면서 미술관은 전시장을 넘어 더 많은 관객들과 소통하기 위한 새로운 방식을 시도하고 있습니다. 관람객과의 거리를 좁히고, 예술적 경험을 다각화하려는 이 흐름은 지금 세계 여러 미술관에서 화두로 떠오르고 있습니다. 이제 미술관은 단순히 작품을 ‘보여주는’ 공간을 넘어, 예술이 존재하는 방식과 그 이면을 함께 사유하는 장소로 변화하고 있다는 이야기이기도 합니다. 《기아디자인매거진》에서는 ‘보이는 것과 보이지 않는 것’, ‘전시와 보존’이라는 상반된 키워드를 중심으로, 전통적인 수장고에서 개방형 수장고로 전환해 나가는 미술관과 박물관의 새로운 태도에 주목합니다. 작품의 이면과 과정을 드러내는 이 변화는, 예술과 관객 사이의 관계를 보다 투명하고 다층적으로 확장시키며, 오늘날 문화기관이 지향해야 할 소통의 방향을 다시금 묻고 있습니다.Editor’s Note

Museums speak to us in quiet ways. A single painting on the wall, a sculpture placed on a pedestal—each one holds a world within it. Yet what we see in the galleries is only a fraction of what a museum truly holds. Behind the scenes, countless artworks remain in silence, tucked away in storage. These spaces are not merely for safekeeping. They are time capsules where the value and history of art are preserved and layered over time. Lately, however, these hidden spaces have begun to open up. More museums are embracing transparency by revealing their storage areas, inviting the public into spaces once considered off-limits. Through open storage and digital archiving, institutions are creating new ways to connect with audiences beyond traditional exhibitions. This shift is more than a logistical change. It reflects a broader transformation in how museums define their role. Around the world, cultural institutions are rethinking how art is shared, experienced, and remembered. By narrowing the gap between preservation and presentation, they are crafting more intimate and multifaceted encounters with art. In this issue of Kia Design Magazine, we explore this evolving attitude. Focusing on the contrast between what is seen and what remains unseen, we look at how museums and archives are transitioning from closed, curated spaces to more open and reflective environments. As the walls of storage rooms become transparent, so too does the relationship between art and audience. These changes invite us to reconsider not just how we view art, but how we engage with its hidden stories, its quiet labor, and the time that sustains it.

About. 조아라 큐레이터

갤러리와 미술관, 박물관에서 10년 간 미술과 엮여 살아온 큐레이터 조아라. 그가 처음 미술에 매료된 순간은 한 점의 그림 앞에서 였습니다. 미술사를 공부하고 전시를 기획하며 보낸 시간들, 그리고 일상 속에서 예술 곁에 머물던 순간들 속에서 그는 때로는 위로를 건네고, 때로는 생각의 방향을 바꿔준 작품과 예술가들을 마주하며 오랜 시간을 지나왔습니다. 서울시립미술관 큐레이터 재직 시절부터 여러 전시를 기획하고 다양한 글을 써 온 그는, 미술에세이 <미술이 나를 붙잡을 때>를 펴내기도 했습니다.

About Jo Ara, Curator

For over a decade, Jo Ara has lived alongside art—moving between galleries, museums, and cultural institutions. Her journey began with a single moment of wonder in front of a painting. Since then, she has studied art history, curated exhibitions, and remained close to the presence of art in everyday life. Throughout the years, she has encountered works and artists that offered comfort, challenged her perspective, and quietly shaped her thinking. From her time as a curator at the Seoul Museum of Art to her many projects since, she has dedicated herself to making space for art to speak to people in meaningful ways. Jo Ara is also the author of When Art Holds Me Still, a collection of personal essays that reflect her deep engagement with art—not just as a professional, but as someone who believes in its power to connect, to question, and to heal.

보이지 않았던 미술관, 수장고

The Invisible Side of the Museum: The Art of Storage

수장고(收藏庫)는 단순한 ‘창고’가 아닙니다. 이곳은 단지 작품을 보관하는 장소를 넘어, 미술관의 본질을 가장 밀도 높게 품고 있는 공간이라 할 수 있습니다. 적정 온도와 습도, 조명과 보안 등 작품의 생애 주기를 지탱하는 모든 조건이 정밀하게 설계되어야 하며, 보존처리와의 연계 속에서 끊임없이 관리되는 살아 있는 시스템이기 때문입니다. 또한 수장고는 미술관의 정체성과 큐레이션 방향을 고스란히 드러내는 거울이기도 한데, 이는 어떤 작품을, 어떤 맥락 속에서 수집하고 보존하는가에 따라 미술관이 추구하는 철학과 관점이 드러나기 때문입니다.

그렇기에 수장고는 부수적인 시설이 아니라, 미술관의 심장부라 불러도 과언이 아닙니다. 전시와 교육, 수집과 보존이라는 미술관의 네 가지 핵심 기능 중 후자, 즉 ‘수집과 보존’을 담당하는 이 공간은 관람객의 눈에는 보이지 않지만, 모든 전시와 교육 활동의 기저를 형성합니다. 이처럼 치밀하게 관리되는 수장고는 오랫동안 외부와 단절된 ‘비공개 공간’으로 존재해왔습니다. 전시장의 화려한 조명 뒤에서, 수장고는 말 그대로 무대 뒤편의 백스테이지였습니다. 작품을 보관하고, 상태를 점검하고, 복원을 준비하는 실무 중심의 공간으로만 여겨져 온 것입니다.

그리고 그 안에는 미처 조명을 받지 못한 작품들, 보존을 기다리는 문화적 기록들이 조용히 쌓여왔습니다. 전통적으로 미술관은 이 공간에 대한 보안을 철저히 했고, 관객은 그 벽 너머에 무엇이 있는지 알기 어려웠습니다. 그렇기에 수장고는 철저히 ‘기능’의 공간으로 정의되었고, ‘이야기’는 오직 전시장에서만 허락되었습니다. 그러나 이제, 그 벽이 흔들리기 시작했습니다. 아직 모두에게 펼쳐지지 않은 수많은 이야기와 가능성이 잠들어 있다는 사실 때문입니다.

A museum’s storage room is far more than a simple warehouse. It is a quiet yet essential space that embodies the museum’s very purpose. Beyond its practical role of holding artworks, it must be meticulously designed to ensure optimal conditions for preservation—controlling temperature, humidity, lighting, and security. It functions as a living, responsive system, deeply intertwined with the work of conservation.

Storage also speaks to a museum’s identity. What is collected, how it is stored, and what is prioritized reflect the institution’s values and curatorial vision. In this sense, storage is not a hidden support facility, but the very foundation from which exhibitions and narratives emerge.

Although rarely seen by the public, the storage room is central to two of the museum’s most vital roles: collection and preservation. These quiet functions underpin everything the audience experiences in the gallery. Yet for much of museum history, storage has remained behind the scenes—a backstage realm devoted to the care, inspection, and restoration of artworks.

Within these spaces, countless works rest in silence, their stories paused rather than forgotten. For decades, the storage room was kept closed, its existence defined by necessity, not imagination. While exhibitions told the museum’s story in public, storage remained a silent partner in the wings.

Today, that narrative is beginning to shift. Museums around the world are opening the doors to these once-hidden rooms, recognizing that within them lie stories as rich and compelling as those on display. The art of storage is becoming a new form of storytelling—one that invites visitors to see not only what is shown, but also what is preserved, protected, and patiently waiting.

숨김과 드러냄의 통합, 열린수장고

Blurring the Line Between Hidden and Seen: The Rise of Open Storage

더 이상 특정 관계자뿐만 아니라, 누구나 미술관의 안과 밖을 들여다볼 수 있어야 한다는 미술관 운영 패러다임의 전환 속에서 ‘개방형 수장고(Open Storage)’라는 새로운 시도가 시작되었습니다. 이는 전통적으로 닫혀 있던 수장 공간을 관람객에게 드러내면서, ‘숨김’과 ‘공개’라는 상반된 태도 사이에서 닫힌 것 속에 열린 가능성을 발굴하는 공간적 메타포라고 할 수 있습니다. 관람객에게 감춰져 있던 수장고를 열어 보여주겠다는 이 실험은, 단순한 ‘공간’의 공개가 아니라 미술관의 권위 구조를 재편하려는 움직임 중 하나이며, 작품을 바라보는 방식 자체를 바꾸려는 시도였습니다. 또한 전시는 큐레이터의 선택과 배제의 결과이기도 하기 때문에, 무엇이 전시장에 놓이고 무엇이 보이지 않는가에 따라 미술관이 추구하는 방향이 드러나기 마련입니다. 개방형 수장고는 이러한 이분법을 흔들고, 전시를 통한 선별을 거치지 않은 더 많은 작품과의 만남을 가능하게 하는 통로이자 수집, 보존, 전시의 기능을 통합한 새로운 형식의 공간이자 담론의 장이라고 할 수 있습니다.

그렇다면, ‘개방형 수장고’의 시작은 언제, 어느 곳에서 시작이 되었을까요? 1976년, 캐나다 브리티시컬럼비아 대학교 인류학박물관(Museum of Anthropology at UBC, MoA)이 그 시작입니다. 기존의 미술관 운영 방식에 의미 있는 전환점을 마련한 MoA는 전시장과 별도로 존재하던 수장고의 일부를 관람객에게 공개함으로써, 관람의 대상이 아니었던 내부 공간을 시각적으로 ‘열어 보이는’ 실험을 처음으로 시도한 것입니다. 이는 단순한 공간 활용을 넘어, 미술관의 작동 방식과 권위 구조에 대한 재해석을 담은 첫 개방형 수장고 사례로 평가를 받고 있습니다.

MoA는 전통적인 수장고와 달리, 일부 수장고 공간을 유리벽과 개방형 진열장을 통해 시각적으로 관람객에게 공개했습니다. 진열장 속 유물들은 단순히 전시된 것이 아니라, 여전히 연구·보존 중인 상태로 존재하며 ‘살아 있는 수장고’로 기능했습니다. 이러한 경우 관람객은 이 과정을 있는 그대로 들여다보며, 유물과의 ‘대면’이 아닌 ‘관찰’이라는 새로운 관람 경험을 하게 됩니다. 이는 미술관이 전시 작품을 일방적으로 선별해 보여주는 권위 있는 공간이라는 인식을 넘어서, 수많은 유물들이 동등하게 존재하고 있다는 사실을 공유하는 장으로 전환한 것입니다. 특히 주목할 점은, MoA가 이 같은 공간 디자인을 통해 원주민 공동체의 관점과 목소리를 수장고 안으로 끌어들였다는 점입니다. 단순히 유물을 보관하고 진열하는 데 그치지 않고, 그 유물의 문화적 맥락과 공동체의 기억까지 함께 보존하는 구조를 지향한 것인데요, 이는 수장고를 단순한 보관창고에서 ‘문화적 대화의 장소’로 확장시킨 혁신적인 시도였습니다.

A quiet yet profound shift is underway in how museums define their role. The traditional model—where only select works are presented in curated exhibitions while the majority remain concealed in storage—is being reexamined. At the heart of this rethinking lies a new concept: open storage.

More than a novel display strategy, open storage represents a philosophical transformation. It opens spaces that were once reserved for curators, conservators, and specialists to the public, breaking down the wall between institutional authority and audience access. By exposing what was once hidden, open storage invites viewers to consider what lies behind the scenes—not just physically, but ideologically. It is a spatial metaphor that reveals the tension between concealment and transparency, order and possibility.

Traditionally, exhibitions are shaped by curatorial selection—what is included, what is excluded, and how stories are told. Open storage disrupts this binary. It offers a raw, unfiltered look into the museum’s collection, creating new forms of encounter not mediated by narrative framing. It is a space where collecting, preserving, and displaying converge, forming a hybrid zone of access and inquiry.

The origins of open storage can be traced to a pivotal moment in 1976, when the Museum of Anthropology (MoA) at the University of British Columbia in Canada introduced a bold new spatial concept. MoA became the first institution to make parts of its storage facilities visible to the public. By replacing opaque walls with glass and placing objects in open-view cases, the museum invited visitors into the behind-the-scenes world of conservation and research.

But this was more than a clever design solution. MoA’s approach fundamentally challenged how museums function. Objects were no longer merely curated relics; many remained in ongoing states of study or preservation. The museum thus transformed from a stage of completed narratives to a site of active observation. Visitors were no longer passive recipients of curated meaning—they became witnesses to the life of objects in flux.

Equally significant was MoA’s commitment to honoring Indigenous perspectives. The museum did not simply display cultural artifacts. It sought to preserve their histories and living relationships. By making storage visible and inclusive of community voices, MoA reframed the storage room as a site of cultural dialogue rather than static containment. Open storage, then, is not just an architectural gesture. It is a curatorial and ethical one. It invites us to reconsider not only what we see, but how we see. It asks us to acknowledge the vastness of what remains unseen, and to imagine museums not as vaults of authority, but as evolving spaces of transparency, care, and shared memory.

백스테이지의 모든 과정을 공유하다

Revealing the Backstage: When Museums Share the Whole Process

이러한 흐름은 다양한 형태로 전 세계 미술관과 박물관에 영향을 미쳤습니다. 런던의 빅토리아 앤 앨버트 박물관(Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A)은 소장품 중 일부를 진열장 형태로 구성하여 ‘보이는 수장고(Visible Storage)’로 상시 공개를 하기 시작했습니다. 일반 전시와 달리, 큐레이터의 선별 과정 없이 작품 다수를 압축적으로 보여주는 방식으로, 이곳의 세라믹 갤러리는 여러 시대와 대륙의 도자 컬렉션 26,500여 점을 층층이 쌓아 올린 진열장을 통해 전시와 보관을 겸하고 있으며, 소장품 간의 상호 관계와 연대기적 맥락을 관객 스스로 발견하게끔 유도합니다. 미국 로스앤젤레스의 더 브로드(The Broad) 경우 미술관 중앙부에 위치한 수장고 벽면에 유리창을 설치해, 관람객이 내부의 작품 보관 상태를 엿볼 수 있도록 설계함으로써 관람자는 이 유리 너머로 아직 전시되지 않은 작품의 존재를 인식하게 되며, 전시라는 행위 이면의 시간과 과정을 상상할 수 있게 됩니다.

This shift toward openness is shaping museums and galleries across the world in new and meaningful ways. One notable example is the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London. Departing from traditional curatorial models, the museum has introduced visible storage displays that present large numbers of objects without the usual process of selection and interpretation. In its Ceramic Galleries, over 26,500 pieces spanning eras and continents are arranged densely in open cases. These vitrines serve both as storage and exhibition, encouraging visitors to discover connections and historical patterns on their own.

Across the Atlantic, The Broad in Los Angeles offers another innovative approach. At the heart of the museum lies a glass wall that reveals part of its storage facility. Visitors are given a glimpse into the vast collection that has yet to be displayed. This architectural transparency allows them to sense the presence of artworks still resting in the shadows—awaiting their moment in the spotlight. In doing so, it invites us to imagine the unseen rhythms behind exhibition: the time, the decisions, the quiet life of objects not yet on view.

By pulling back the curtain, these institutions are transforming the visitor experience. What was once backstage is now part of the narrative, fostering a more inclusive and layered understanding of how museums work, and what stories remain to be told.

‘보이는 수장고’ 개념을 확장한 형태로, ‘수장형 박물관(Storage Museum)’의 대표적 사례인 샤울라거(Schaulager)가 있습니다. 이 기관은 2003년 스위스 바젤 인근 뮌헨슈타인(Münchenstein)에 개관하였으며, 로렌츠 재단(Laurenz Foundation)의 소장품을 중심으로 구성되었습니다. 샤울라거는 전통적인 미술관과 아카이브의 경계를 허문 공간으로 평가받으며, 연구자와 대중 모두에게 개방된 하이브리드 수장고로 기능합니다. 건축은 헤르조그 & 드 뫼롱(Herzog & de Meuron) 건축사무소가 맡아, ‘기능성과 미학의 융합’을 공간으로 실현하였습니다. 샤울라거는 전통적인 미술관, 보존실, 아카이브의 경계를 허물고 작품의 연구·보존·전시가 한 흐름 안에서 이루어지는 공간으로 구성되어 있습니다. 일반 대중에게 상시 개방되지는 않지만, 연구자나 예술 전문가에게는 작품 보존 상태와 설치 조건까지 접근이 가능하도록 하여, 작품이 어떻게 보관되고 관리되는지에 대한 투명성을 높이는 데에 집중합니다. 특히, 불규칙한 규모와 형태의 전시 공간을 다수 갖추고 있어 대형 설치미술이나 복합 매체 작품도 원형 그대로 보존하고 전시할 수 있다는 것이 큰 장점입니다. 샤울라거는 단순히 관람의 대상이 아닌, 작품이 ‘존재하는 방식’ 자체를 교육하고 연구하는 플랫폼으로 기능합니다. 이들의 소장품은 특정 전시를 위한 역할에 국한되지 않고, 큐레이터, 복원가, 예술가의 장기적 협업 속에서 ‘살아 있는 아카이브’로 지속적으로 해석되고 활용됩니다.

Expanding on the concept of visible storage, the storage museum is emerging as a radical rethinking of how museums engage with space, collection, and the public. One of the most pioneering examples is Schaulager, located in Münchenstein near Basel, Switzerland. Opened in 2003 by the Laurenz Foundation, Schaulager redefines the boundaries between archive, research facility, and exhibition space. It serves both specialists and the public, functioning as a hybrid model of access and inquiry.

Designed by Herzog & de Meuron, the architecture of Schaulager embodies a seamless fusion of functionality and aesthetic intention. The facility breaks down the silos of the traditional museum—display galleries, conservation rooms, and storage areas—to form a unified ecosystem where artworks can be studied, preserved, and occasionally exhibited in a single flow.

While not open to the general public on a daily basis, Schaulager provides unprecedented access to researchers and art professionals. They are able to examine how artworks are stored, conserved, and even installed, bringing transparency to the processes usually hidden behind museum walls. The facility includes large, adaptable spaces that can accommodate monumental installations and complex media works without compromising their original form. Schaulager is not merely a place to see art—it is a place to understand how art exists. Its collection is activated continuously through collaboration among curators, conservators, and artists, transforming it into a living archive that evolves through long-term dialogue.

보이만스 판 뵈닝언은 미술관 전체가 열린 수장고로 되어 있다.

Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen ©shutterstock

여기에서 한 발 더 나아간 네덜란드의 데포 보이만스 판 뵈닝언(Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen)은 기획 단계부터 ‘전면 개방형’ 수장고를 표방한 곳으로 기존의 보이만스 판 뵈닝언 미술관의 수장 공간이었던 영역을 관람객에게 온전히 개방한 덕분에 약 15만 점에 달하는 소장품을 14구역으로 나누어 보관하면서, 관람객이 실제 수장고 내부를 이동하며 감상할 수 있도록 설계되었습니다. 이곳의 특징은 보관 중인 작품뿐 아니라 작품 운반, 보존 처리, 연구 등 ‘백스테이지’의 모든 과정을 관람객에게 공개한다는 점입니다. 각 구역은 온습도 조건에 따라 분류되어 있기에 미술품의 재료별 보관 원칙 또한 확인할 수 있습니다. 관람객은 안내 경로를 따라 이동하면서, 유리창 너머로 복원가들이 작업 중인 모습을 볼 수 있고, 작품이 실제로 포장되고 운송되는 과정까지 경험하게 됩니다. 이는 단순히 결과물로서의 ‘작품’을 감상하는 기존의 방식에서 벗어나, 미술관 운영의 비가시적 영역 전체를 ‘콘텐츠화’하는 새로운 시도라고 할 수 있습니다. 또한 데포는 민간기업과 시민의 후원으로 운영되는 공공 프로젝트로, 미술관과 지역 사회의 ‘공유 자산’으로 기능합니다. 일부 공간은 일반 시민도 대여할 수 있고, 옥상 정원과 레스토랑은 지역민을 위한 커뮤니티 허브 역할까지 겸하고 있습니다. 이처럼 데포는 미술관의 투명성, 공공성, 지속가능성을 극대화한 21세기형 수장고 모델로 평가받고 있으며, 2023년에는 유럽 박물관 포럼(European Museum of the Year Awards, EMYA)에서 특별상을 수상하며 예술, 대중, 컬렉션 보존을 결합한 혁신적인 접근 방식으로 찬사를 받기도 했습니다.

Pushing this vision even further, the Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam has taken the idea of openness to a new level. Developed as an extension of the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, the Depot was designed from the outset to be fully accessible to the public. With over 150,000 objects housed in 14 climate-controlled zones, the building invites visitors to walk through the very spaces where artworks are stored, transported, and cared for.

What sets the Depot apart is its radical transparency. Visitors can observe every stage of the collection’s backstage life—from restoration and conservation to packing and transport. Along carefully guided paths, they peer through glass walls to watch conservators at work, offering a rare glimpse into the daily labor that sustains museum collections. This approach transforms what was once invisible infrastructure into active content, allowing audiences to engage not just with finished artworks but with the systems that preserve them.

The Depot is also a model of public-private partnership, funded through a mix of municipal support, private donors, and corporate sponsorship. It positions itself as a shared cultural asset, with certain areas available for public use. Its rooftop garden and restaurant serve as community spaces, blending the roles of museum and civic center.

This 21st-century storage model has received widespread acclaim. In 2023, the Depot was awarded a special prize at the European Museum of the Year Awards (EMYA) for its innovative integration of art, public access, and collection care. It exemplifies how transparency, sustainability, and public value can converge within museum practice, offering a glimpse into a future where the museum’s hidden core becomes its most vital point of connection.k.

전시형 수장고가 자리 잡기 시작한 국내 미술관과 박물관

Visible Storage in Korea: Turning the Museum Inside Out

한국에서도 개방형 수장고에 대한 관심은 점차 높아지고 있습니다. 그 중심에는 2018년 개관한 국립현대미술관 청주관이 있습니다. 청주관은 국립현대미술관의 첫 지역 분관으로, ‘저장소가 곧 전시장이 되는 공간’이라는 개념을 바탕으로 기획되었습니다. 단순히 보관 기능만을 수행하던 기존 수장고와 달리, ‘전시형 수장고’이라는 혁신적인 모델을 제시하며, 소장품 보존·연구·교육·전시 기능을 통합한 복합 플랫폼으로 설계되었습니다.

관람객은 수장형 전시실뿐 아니라, 유리창 너머 수장고 내부에 정돈된 상태로 배치된 수많은 작품들을 관람할 수 있습니다. 회화, 조각, 설치미술 등 다양한 장르의 작품이 소재, 크기, 시기 등에 따라 체계적으로 정리되어 있으며, 미술관의 내부 작동 방식이 투명하게 드러납니다. 또한 복원 전문가들이 실제로 작업을 수행하는 보존처리실의 모습도 공개되어, 미술품이 전시되기까지의 과학적, 물리적 과정까지 함께 체험할 수 있도록 구성되어 있습니다. 이처럼 청주관은 미술관의 ‘백스테이지’를 새로운 콘텐츠로 전환시켜, 관람객의 이해와 몰입을 확장하는 시각 교육의 장으로 활용하고 있습니다.

이후 국립민속박물관 역시 이러한 흐름에 동참하며 개방형 수장고를 적극 도입하였습니다. 2021년, 100만여 점에 달하는 소장 유물 중 일부를 공개하는 개방형 아카이브 공간을 새롭게 조성하였으며, 관람객 누구나 큐레이션의 틀 없이 민속 자료를 열람할 수 있는 구조로 설계하였습니다. 도자기, 농기구, 의복, 공예품 등 한국인의 삶과 밀접한 생활유물이 다수 포함되어 있어, 전시장을 벗어난 민속유물의 친숙함과 정서를 더욱 가까이 느낄 수 있게 합니다. 특히 이곳에서는 보관 과정, 분류 체계, 연구 노트 등을 함께 노출함으로써 관람객의 이해도를 높이고, 박물관과 관람객 사이의 거리감을 줄이는 정서적 소통의 계기를 마련합니다.

또 하나의 주목할 만한 사례는 서울공예박물관입니다. 안국동에 위치한 이 박물관은, 공예의 예술성과 실용성 모두를 체감할 수 있도록 구성된 장르 특화형 박물관으로, ‘보이는 수장고’를 전략적으로 운영하고 있습니다. 일부 직물 및 섬유 공예 소장품은 유리창을 통해 공개되어 있으며, 섬세한 자수나 염색 기법이 그대로 드러나는 보관 방식 덕분에, 관람객은 일반 전시에서는 보기 어려운 소재의 촉감과 제작 방식에 대한 감각적 이해를 얻을 수 있습니다. 더불어 복원 작업이나 보존처리 과정을 일부 주기적으로 공개함으로써, 공예품이 가진 특유의 물성(物性)과 그것의 보존가치에 대한 학습의 장을 제공합니다.

In recent years, Korean museums have increasingly embraced the concept of open and visible storage, reshaping how collections are experienced by the public. At the forefront of this shift is the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Cheongju, which opened in 2018 as the institution’s first regional branch. Built on the radical premise that a museum’s storage space could itself become a site of exhibition, Cheongju has redefined the boundaries between preservation and display. Rather than hiding its stored collections behind closed doors, the museum has designed its facilities as a hybrid platform for conservation, research, education, and exhibition. Visitors can explore the storage galleries directly or view the neatly organized collection through transparent glass walls. Paintings, sculptures, and installations are systematically arranged by medium, size, and era, offering a glimpse into the museum’s internal operations. Even the conservation labs—where experts restore and examine artworks—are open to view, transforming the backstage processes of the museum into part of the public experience.

This pioneering model has since inspired other institutions. In 2021, the National Folk Museum of Korea followed suit, establishing an open archive space that allows visitors to freely browse parts of its vast collection of over one million artifacts. This area breaks away from conventional curatorial frameworks, allowing for direct encounters with everyday cultural objects—ceramics, tools, clothing, and crafts—that reflect the lived history of the Korean people. By revealing not only the objects themselves but also their classification systems, storage methods, and research notes, the museum fosters emotional and intellectual connection, narrowing the distance between institution and audience. Another noteworthy example is the Seoul Museum of Craft Art, located in the historic Anguk-dong neighborhood. As a museum dedicated entirely to the artistry and functionality of craft, it has strategically implemented visible storage as part of its design philosophy. Certain textile and fiber-based works are stored behind glass walls, allowing visitors to closely observe intricate techniques such as embroidery and natural dyeing. This sensory proximity to materials rarely spotlighted in traditional galleries offers new ways of seeing and understanding. In addition, periodic public demonstrations of restoration and conservation provide valuable insight into the material integrity of crafts and the delicate processes required to preserve them. Across these institutions, the storage room is no longer a hidden, utilitarian space. It is becoming a transparent, educational, and emotionally resonant part of the museum’s mission. By making the unseen visible, Korean museums are creating a new kind of cultural encounter—one where preservation is not only a backstage task, but a story worth sharing in its own right.

시공간의 경계를 넘나드는 디지털 스토리지로 만나다

Digital Storage Beyond Time and Space: Museums in the Age of Open Access

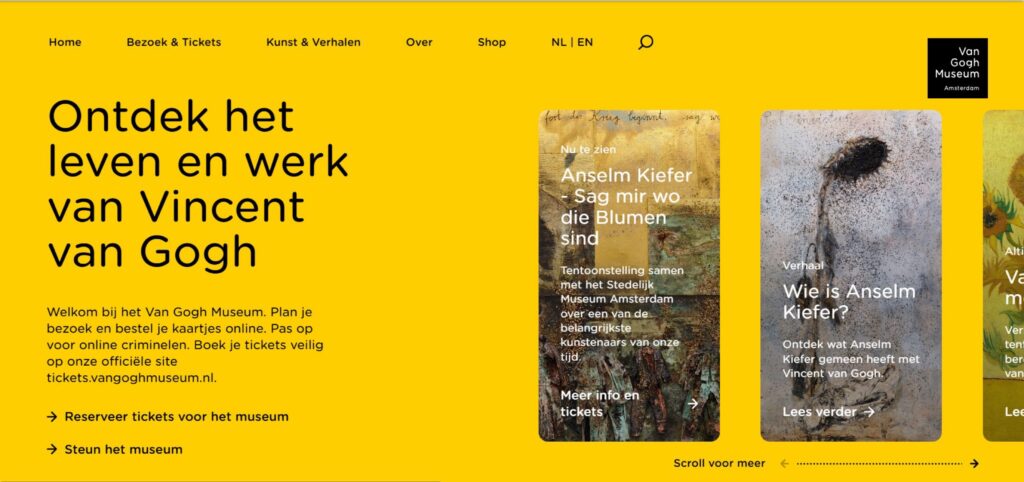

열린 수장고는 보존과 전시의 경계를 허물며 세계 주요 미술관들이 ‘보이는 수장고’나 ‘수장형 박물관’, ‘아카이브 센터’ 등으로 확장되더니, 이젠 시간·공간을 넘나들기 시작했습니다. 물리적 개방에 머무르지 않고, 디지털화를 통한 또 하나의 ‘열린 수장고’를 관람객에게 공유하기 시작한 것이죠. 대표적으로 뉴욕의 브루클린 뮤지엄과 암스테르담의 반 고흐 뮤지엄이 이 분야에서 선도적인 사례로 꼽히고 있습니다. 브루클린 뮤지엄은 자체 홈페이지를 통해 소장품의 다양한 이미지(정면, 측면, 세부 컷 등)는 물론, 시대, 재료, 색상 등을 기반으로 한 연관 작품까지 함께 제시함으로써 관람객의 자발적인 탐색과 학습을 유도합니다. 또한 사용자로부터 받은 질문에 직접 응답하고 그 내용을 공유하는 등 상호적인 소통 구조를 마련해, 단순한 정보 제공을 넘어 디지털 플랫폼으로서의 미술관 기능을 강화하고 있습니다.

반 고흐 뮤지엄 역시 ‘Art & Stories’라는 섹션을 통해 작품에 얽힌 이야기와 작가의 삶을 주제별 콘텐츠로 재구성하며, 대중의 흥미와 이해도를 높이고 있습니다. 이러한 노력은 웹 콘텐츠의 우수성을 평가하는 국제 어워드인 ‘웨비 어워즈(Webby Awards)’에서 두 차례 수상이라는 성과로 이어졌습니다.

이 같은 흐름은 뉴욕 현대미술관(MoMA)에서도 뚜렷하게 나타납니다. MoMA는 1929년 개관 이래의 전시 기록을 디지털 아카이브에 포함시켜, 전시 연표와 작품 이미지, 도록 PDF, 큐레이터 기록 등 방대한 과거 활동 자료를 온라인에서 열람할 수 있도록 했습니다. 이를 통해 MoMA는 단순한 열람 기능을 넘어 연구자와 일반 관람객 모두에게 동등한 접근성을 제공하며, 미술관이 ‘지식 자원으로서의 공공플랫폼’으로 기능할 수 있는 가능성을 보여주고 있습니다.

이처럼 주요 미술관들이 구현하는 디지털 수장고는 단순한 이미지의 나열에 그치지 않습니다. 정보와 이야기, 경험이 유기적으로 연결되는 구조를 지향하며, 미술관의 역할을 물리적 공간을 넘어선 확장된 문화 플랫폼으로 관람객들을 만나고 있습니다.

The idea of the open storage room—once rooted in physical access and transparency—is evolving into something far more expansive. As museums around the world adopt visible storage displays, storage-centered museum models, and hybrid archive spaces, a new frontier is emerging: the digital storage room.

This next chapter moves beyond the architectural, crossing the boundaries of time and space through digital platforms. Leading the way are institutions like the Brooklyn Museum in New York and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, both of which have pioneered new ways to share their collections online.

The Brooklyn Museum offers a dynamic digital archive that goes well beyond standard catalog entries. Its website allows visitors to explore high-resolution images of its collections from multiple angles—front, side, and detail views—while also suggesting related works through filters like era, material, and color. This design encourages self-directed exploration and learning. In addition, the museum answers visitor-submitted questions and publicly shares those exchanges, establishing an interactive model of engagement that transforms its digital presence into a true extension of the museum experience.

Similarly, the Van Gogh Museum’s Art & Stories section invites audiences to dive deeper into the artist’s life and works through thematic narratives. This approach not only enhances understanding but also connects emotionally with visitors by weaving together context, biography, and visual experience. These efforts have not gone unnoticed—the museum has twice been recognized by the Webby Awards for excellence in digital content.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York demonstrates the scholarly potential of digital storage even more explicitly. MoMA has digitized its entire exhibition history since its founding in 1929, providing access to exhibition timelines, artwork images, catalog PDFs, and curatorial notes. This resource serves both the academic and general public, positioning the museum as a public knowledge platform and a model of institutional transparency.

In each case, these museums are building more than just online databases. They are constructing digital ecosystems in which artworks, information, and storytelling are deeply interconnected. The digital storage room is not a flat archive but a living, growing interface—one that extends the museum’s reach, reshapes its public role, and reimagines how we engage with art. Through these efforts, museums are no longer defined by their physical walls. They are becoming fluid cultural platforms, capable of reaching wider and thinking deeper, meeting their audiences not just where they are, but wherever they may go.

미술관, 태도를 바꾸고자 하는 실천적 제안, 개방형 수장고

Open Storage: A Practical Proposal to Change Museum Attitudes

개방형 수장고는 단순히 많은 작품을 전시하는 공간이 아닙니다. 그것은 미술관이 자신이 무엇을 소장하고 있는지를 감추지 않고 드러내겠다는 하나의 선언이며, 관람객과 일정한 거리를 두던 문화기관의 태도를 바꾸고자 하는 실천적 제안입니다. 전통적으로 미술관은 일부 작품만을 전시하고 나머지는 비공개 수장고에 보관해 왔습니다. 하지만 개방형 수장고는 그 가려진 이면을 외부에 투명하게 공개함으로써, 미술관이 더 이상 닫힌 권위의 공간이 아니라 공유와 참여의 공공 플랫폼임을 드러냅니다. 이러한 변화는 관람 방식의 근본적인 전환을 이끕니다. 관람객은 단순히 완성된 전시 결과물을 감상하는 것을 넘어서, 작품이 어떻게 분류되고 보존되며 연구되는지까지 간접적으로 경험할 수 있습니다.

이는 미술관의 내부 작동 원리에 접근하는 방식으로, 관람객에게 새로운 차원의 이해를 제공합니다. 이 과정을 통해 관람자는 단순한 문화 소비자에서 지식의 공동 생산자로 나아가며, 미술관과의 관계 역시 보다 수평적이고 유기적인 방향으로 재편됩니다.

물론 이러한 시도에는 현실적인 제약도 따릅니다. 수장고는 본래 작품 보존을 최우선으로 고려하는 공간이기 때문에, 외부에 공개할 경우 보안 문제나 온습도 유지, 빛 노출 등에 있어 이상적인 조건을 유지하기 어려울 수 있습니다. 장기적으로는 이러한 환경이 작품 보존에 부담을 줄 수 있다는 우려도 제기됩니다. 개방성과 안정성 사이에서 균형을 찾는 일은 여전히 미술관 운영의 중요한 과제로 남아 있습니다.

그럼에도 불구하고 많은 미술관들은 수장고를 단순한 저장 공간이 아닌 ‘살아 있는 아카이브’로 만들고자 하는 의지를 놓지 않고 있습니다. 최근에는 물리적 공간의 개방을 넘어, 디지털 기술을 활용한 온라인 소장품 공개도 활발히 이루어지고 있습니다. 이를 통해 미술관은 전시 기관을 넘어 연구와 교육, 기록을 수행하는 지식 플랫폼으로 진화하고 있습니다. 개방형 수장고는 공간을 여는 것을 넘어, 미술관의 정체성과 역할을 근본적으로 다시 묻는 동시대적 실험입니다. 작품을 ‘가두는’ 것이 아니라 ‘살리는’ 방식으로 다루고, 관람객을 감상의 주체로 세우는 이 시도는 여전히 진행 중인 도전이자, 미술관의 공공성과 연구 기능을 아우르는 새로운 문화적 가능성의 장을 제시하고 있습니다.

Open storage is not merely a space to display more artworks. It represents a declaration by museums to no longer hide what they hold in their collections and is a practical proposal aimed at transforming the traditional distance between cultural institutions and their visitors. Traditionally, museums have exhibited only a fraction of their collections, keeping the rest locked away in closed storage. By transparently revealing these hidden spaces, open storage signals that museums are no longer closed, authoritative institutions but shared, participatory public platforms.

This shift leads to a fundamental change in how audiences engage with art. Visitors move beyond simply viewing finished exhibitions to indirectly experiencing how artworks are categorized, preserved, and studied. It offers a new dimension of understanding by providing insight into the museum’s internal operations. Through this process, visitors evolve from passive cultural consumers to co-producers of knowledge, and the relationship between museum and audience becomes more horizontal and organic.

Of course, such efforts come with practical challenges. Storage spaces prioritize the preservation of artworks, so opening them to the public raises concerns about security, maintaining ideal temperature and humidity, and exposure to light. Over time, these factors could threaten the safety of the collections. Balancing openness with conservation remains a critical ongoing challenge for museum management.

Nevertheless, many museums remain committed to transforming storage into “living archives” rather than mere repositories. Increasingly, this commitment extends beyond physical openness to actively sharing collections online through digital technologies. Museums are evolving into knowledge platforms that encompass research, education, and documentation, transcending their traditional exhibition roles. Open storage is more than just opening a space—it is a contemporary experiment that fundamentally reexamines a museum’s identity and role. It treats artworks not as locked-away objects but as living entities and positions visitors as active participants in appreciation. This ongoing challenge offers a new cultural possibility that integrates public access with the museum’s functions of research and stewardship.