익숙함을 낯섦으로 평범함을 이국적으로 이방인이 담은 한국의 집 – 잉고 바움가르텐

Familiarity transformed into the unfamiliar, The ordinary perceived through the exotic eyes, A foreigner’s portrait of a Korean house - Ingo Baumgarten

Localler

새롭게 떠오르는 문화를 발견해 융합해 나가는 ‘문화의 선구자 Culture Vanguard’ 역시 기아 디자인 크리에이티브 철학의 문화적 특징 중 하나입니다. 기아디자인매거진은 Localler라는 메뉴를 통해 ‘문화의 선구자 Culture Vanguard’라는 타이틀로 한국에서 살고 있는 현지 외국인, 외국에서 살고 있는 현지 한국인들의 경계 없는 스토리를 보여줍니다.

Localler

As a Culture Vanguard, who discovers and integrates emerging culture, is another feature of Kia Design’s creative philosophy. In the Localler menu, Kia Design Magazine presents stories about foreigners living in Korea, as well as Koreans living abroad, under the title ‘Culture Vanguard’.

풍경이 익숙해지면 우리는 그것에 큰 감흥을 느끼지 못한 채 스쳐 지나친다. 하지만 익숙한 듯한 풍경 속에서도 섬세한 관찰을 통해 익숙한 것을 낯설게, 평범한 것을 아름답게 화폭에 풀어내는 이가 있다. 바로 독일 화가 잉고 바움가르텐(이하 잉고). 일상에서 건축의 구조, 소재 등을 탐구하며, 자신만의 상상을 스토리텔링 하여 잉고만의 시선을 만들어 낸다. 잉고의 그림을 마주하면 마치 ‘이상한 나라 앨리스’로 빨려가듯 새로운 세상이 눈앞에 펼쳐진다. 그래서 우리는 무심코 스쳐 지나갔던 풍경을 다시금 돌아보게 된다. 16년째 한국에 살면서 서울을 관찰하며, 한국의 주택과 건물을 자신만의 해석으로 그리며 한국인들과 상호작용을 하는 잉고의 이야기가 시작된다.

When we become familiar with a landscape, we often pass by it without much thought or feeling. Yet, there are those who, through careful observation, manage to transform the familiar into the unfamiliar and the ordinary into the beautiful, expressing it through drawing. One such individual is the German painter Ingo Baumgarten. He explores the structures and materials of architecture in everyday life, weaving his unique imagination into a distinct storytelling style. Encountering Ingo’s artwork feels like being drawn into a new world, much like being pulled into “Alice in Wonderland.” This prompts us to revisit the landscapes we once overlooked. And this is the beginning of the story of Ingo, who has been observing Seoul after living in Korea for 16 years and interpreting its houses and buildings in his own way, and engaging with the local people.

“마치 두 손을 모으고 기도하는 느낌이 들지 않나요?”

-잉고 바움가르텐“Doesn’t it resemble hands clasped in prayer?”

-Ingo Baumgarten

독일의 서부 하노버 교외 작은 마을에서 태어나 그곳에서 학창 시절을 보냈다. 그 학생은 풍부한 문화가 있는 대도시를 동경했고, 미술학도이자 젊은 예술가가 되고자 파리로 떠났다. 독일에서 학업을 마친 후 ‘파리 시각예술고등예술원 Institute of Higher Studies in Visual Arts Paris’에 합격하여 초대받은 것. 그곳에서만 머물지 않고, 대만, 일본, 한국으로 유랑해왔다. 다문화적 관점을 견지한 잉고는 2008년 홍익대학교 교수가 되어 학생들을 가르치고, 1970년에서 1990년 사이에 지어진 콘크리트 주택에 매료되어 한국의 집과 건물을 화폭에 담고 있다.

Born in Hanover, West Germany, later raised up in a small town close to Düsseldorf, Ingo spent his school days there. He always longed for the rich culture of the big cities and set off for Paris to pursue his dream of becoming an art student and a young artist. After ending his studies in Germany, Ingo was accepted and invited to the Institute of Higher Studies in Visual Arts Paris to study. Not limiting himself to Paris, he also traveled to Taiwan, Japan, and Korea. Embracing a multicultural perspective, Ingo settled in Korea in 2008, becoming a professor at Hongik University to teach fine art. Captivated by the concrete houses built between the 1970s and 1990s, he brings Korean homes and architecture to life on canvas.

잉고 바움가르텐이 한국의 주택에 매료된 데에는 유럽에서 나고 자란 환경이 한몫했다. 대부분의 유럽은 일률적으로 집을 짓는다. 지붕의 규격, 방의 구조 등 하나하나 정해진 법규가 있고, 집을 보수하기 위해서는 20년 정도가 흘러야 한다. 반면, 한국의 주택은 전통과 현대의 대비가 뚜렷하면서도 주택의 구조나 형식이 저마다 다르다. 이 대비 속에서 한국인들의 개성이 묻어 있는 저마다의 스토리가 잉고의 시선을 끌었다. 그런 잉고는 한국인이라면 무심코 지나쳤을 지붕을 보고 영감을 얻었다. “마치 두 손을 모으고 기도하는 모습처럼 느껴졌어요.” 이방인 시선에서 한국 주택은 영감의 원천이었고, 한국 주택이나 건물의 한 단면을 극대화하여, 자신만의 상상을 더해갔다. 《기아 디자인 매거진》은 한국적이면서도 한국적이지 않은 잉고 바움가르텐만의 세계가 궁금했다. 한국에서 어떤 매력을 느끼는지, 그 매력을 어떻게 그려내는지 등 한국을 바라보는 잉고의 관점이.

Ingo Baumgarten’s fascination with Korean houses can be traced back to his upbringing in Europe. In most parts of Europe, houses are built uniformly, with specific regulations governing aspects like roof dimensions and room layouts. There are strict laws in place, and houses typically require about 20 years to undergo renovations. In contrast, Korea displays a stark contrast between tradition and modernity, with each home having a unique structure and design. This contrast and unique features of each house caught Ingo’s eyes. And he was inspired by the roof, something many Koreans might pass by without a second thought. “It felt like hands clasped together in prayer,” he remarked. From the foreigner’s point of view, Korean homes were a source of inspiration. By magnifying particular elements of Korean houses and buildings, and blending them with his own imagination, he portrayed the landscapes of Korea in his art. was curious about Ingo Baumgarten’s unique world, one that feels both distinctly Korean and yet not, through the eyes of a foreigner. What was it about Korea that attracted him? How did he translate that allure into his work? And how does Ingo perceive the country?

#한국

블레이드 러너, 한국 영감의 원천

#Korea

Blade Runner, the source of inspiration in Korea

1993년. 대전엑스포를 관람하며 한국과 첫 인연을 맺은 잉고 바움가르텐. 잉고는 경제와 문화가 역동적으로 발전하는 한국의 모습에 깊은 인상을 받았다. ‘파리 시각예술고등예술원’에서 ‘1993 대전엑스포’의 미술품 전시를 기획하던 중 한국의 예술과 문화 탐방을 하는 ‘스쿨 트립(School Trip)’ 프로그램이 함께 기획되었다. 잉고는 그 프로그램에 선발되면서 처음 한국을 방문하면서 ‘역동적인 한국’을 마주했다.

“1993년 여행 중 오래된 전통과 거대한 현대화의 큰 대비가 저에게 깊은 인상을 받았습니다. 한쪽에는 인왕산에는 무당들이 있었고, 다른 한쪽에는 현대식 고층 아파트 건물로 지평선을 이루고 있었죠. 또 동대문 시장에는 다양한 상품과 제품, 서비스가 한곳에 모여 있다는 점이 놀라웠어요. 당시만 해도 지금보다 훨씬 컸던 시장의 규모는 압도적이었고, 벽면 가득 채워진 컬러 TV, 개고기와 새고기까지… 온갖 종류의 직물 사이에서 길을 잃고 헤맸던 기억도 있어요. 그때를 돌이켜보면 영화 <블레이드 러너>의 세트장에 온 듯한 기분이었습니다.”

2008년 한국으로 다시 돌아온 잉고는 전통과 현대의 대조적인 한국의 인상을 찾아 골목을 거닐었다. 그 순간 한국 주택의 모습이 잉고의 눈에 들어왔다.

1993 – the year when Ingo Baumgarten first encountered Korea while visiting Daejeon Expo. He was especially impressed by the country and its dynamic developments in economy and culture. Because the director of the Institute of Higher Studies in Visual Arts Paris had organized the art-exhibition of the Expo ‘93 in Daejeon, organizing a “school trip” to explore Korean art and culture. And that’s how Ingo first came to the country and witnessed the ‘dynamic Korea.’

“During the trip in 1993, I was deeply struck by the stark contrast of old traditions and massive modernization. On one side, there were mudang cults at Inwangsan, and on the other side, the horizon filled with modern high-rise apartment buildings. Dongdaemun Market amazed me with its large variety of goods, products, and services all gathered in one place. The sheer size of the market, which was much larger back then than today, and I remember that I got lost between walls of color TVs, various food stands offering also meat of dogs and baby birds, and textiles of all kind so that I felt like I was in the set of the movie ‘Blade Runner.’”

When Ingo returned to Korea in 2008, he wandered through alleys in search of the contrasting impressions of tradition and modernity he had once experienced. At that moment, the sight of Korean houses caught his eye.

#영감

전통과 현대의 조화를 시도한 집합체

#Inspiration

A collective attempt to harmonize tradition and modernity

Q1.

한국에 정착하게 된 특별한 이유가 있었나요?

Q1.

Was there a special reason

you decided to settle down in Korea?

특별한 계기는 아니었어요. 2008년에 홍익대학교에서 일을 시작하면서 서울에 정착하게 되었습니다. 지금까지 머무르게 된 것도 자연스럽게 흘러왔습니다. 학교에서 학생들에게 미술을 가르치는 것도 좋고, 저의 작업에 한국은 여전히 영감을 주기 때문이죠.

There wasn’t any particular reason. I settled in Seoul in 2008, when I started my work at Hongik University. Staying here until now has just happened naturally. Teaching fine art at an important school is nice, and Seoul and Korea continue to be a source of inspiration for me. My work was also one of the reasons to stay on.

Q2.

작업은 한국 주택을 오브제로 하는 것을 말씀하시는 걸까요?

한국 주택에 매료된 이유는 무엇인가요?

Q2.

Are you referring to your works

with Korean houses as motifs?

What attracted you to Korean houses?

그렇습니다. 1993년 처음 서울을 방문했을 때 서울의 도시 풍경은 콘크리트로 만든 하얀 수평 구조의 붉은 벽돌로 지은 집들이 언덕을 가득 메우고 있었어요. 저에겐 꽤 인상적이었습니다. 제가 살던 독일이나 유럽과는 다른 풍경이기 때문이죠. 그런 주택들은 동대문이나 이태원 일부 지역에 남아 있는데, 도시 재개발이 진행 중이거나 최소한 리모델링으로 곧 사라지게 될 것 같습니다.

Yes, that’s correct. When I first visited Seoul in 1993, the cityscape was dominated in many areas by hills full of houses, made with red brick, with white horizontal structures from concrete. It was quite striking to me because it was so different from the landscape in Germany or Europe where I lived. Now there are just some of those areas left with such houses, like Dongdaemun or Itaewon, but it seems they will also soon disappear due to urban restructuring or at least through remodeling.

Q3.

한국의 주택의 어떤 부분이 다르게 다가왔는지요?

Q3.

What aspects of Korean houses

seemed different to you?

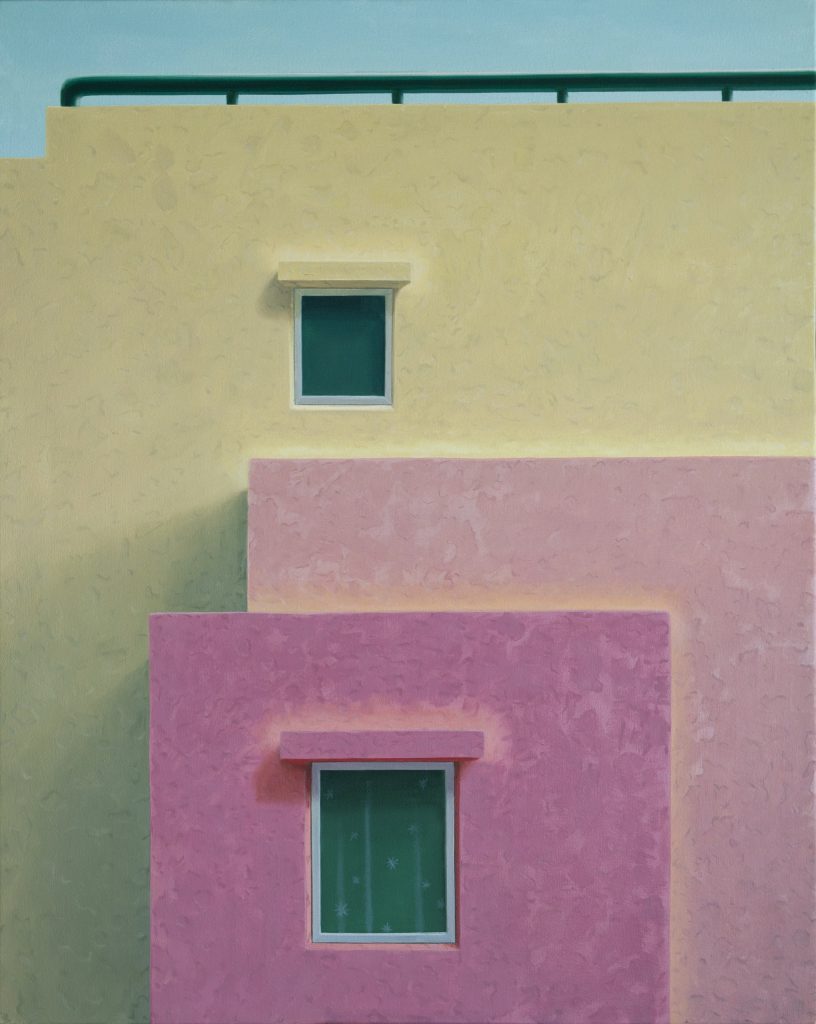

한국에 정착하면서 도시와 주택을 좀 더 자세히 들여다보기 시작했는데요. 제가 살던 지역(서교동, 연남동, 연희동)을 예로 들면 집이나 건물들이 서양과 동양의 아이디어가 융합된 모습이라는 생각을 하게 되었습니다. 미국 주택의 창시자인 프랭크 로이드 라이트 Frank Lloyd Wright의 프레리 스타일* 기법과 닮아 있었죠. 한국의 주택은 현대적인 서양 재료와 건축 기술을 사용한 동시에 대문간이 있는 정원, 확장된 베란다 공간 등 한국의 전통 방식을 적용해 그것이 융합되었다는 걸 알 수 있었습니다. 특히 장식적 요소가 콘크리트로 구현되었지만, 전통적인 목조 건축의 형태에서 영감을 받은 것이라 생각이 됩니다.

* 프레리 스타일 경사가 완만한 지붕과 지붕 바로 밑으로 슬레브 구조가 밖으로 나오게 한 2층의 베란다식의 건축법

After I settled in Korea, I began to take a closer look at the city and its houses. In the areas where I lived, such as Seogyo-dong, Yeonnam-dong, and Yeonhui-dong for example, I was fascinated by the fusion of Western and Eastern ideas and concepts of the houses and buildings. It resembled the Prairie Style* techniques of Frank Lloyd Wright, the founder of American housing. Korean houses used modern Western materials and construction techniques while incorporating traditional Korean methods such as gated gardens and extended veranda spaces. Many decorative elements were executed in concrete but inspired by forms of traditional wooden constructions.

*Prairie Style refers to a construction method where a gently sloping roof with slab structures, protruding just below the roof, extends out to create a veranda-like space on the second floor.

#관찰

시각인류학 관점에서 접근

#Observation

Approach from the perspective of visual anthropology

Q4.

한국 주택의 지붕, 난간이나 옥상의 테라스 등

일상적 공간에 관심이 많은 것 같은데요.

그 부분들이 동양과 서양의 융합으로 해석되는 걸까요?

Q4.

It seems like you are very interested in everyday things of

Korean houses, like the roof, railing, and terrace.

Do you interpret those elements

as a fusion of Eastern and Western styles?

맞습니다. 건축물은 사회의 문화와 정서가 집약되어 있다고 보기 때문에 구성과 색채, 비례 등을 재구성해 평범한 공간에 새로운 미학적 가치를 부여하고자 합니다. 제가 ‘시각인류학’이라는 관점에서 작업에 접근하는 이유도 이 때문입니다. 2002년경 독일 대학교 홈페이지에 올라와 있던 용어인데요. 사회의 구성원이면서 동시에 일정한 거리를 두고 참여적인 관찰을 통해 일상과 문화, 사회를 탐구하고 그 결과를 이미지화하는 것을 말합니다.

Yes, that’s correct. Since architecture embodies the culture and sentiment of a society, I aim to reimagine composition, color, and proportion to bring new aesthetic value to ordinary spaces. This is why I approach my work from a “visual anthropology” perspective. This is the term I first encountered around 2002 on the website of a German university. It refers to the practice of exploring daily life, culture, and society through continuous observation while maintaining a certain distance, and translating them into expressions.

Q5.

시각인류학에 대해

조금 더 구체적으로 설명해주시면 좋을 것 같습니다.

Q5.

Please elaborate a bit more

on visual anthropology.

유럽에서는 집을 ‘영원’의 개념으로 보고 그에 따른 사회적, 문화적인 양상이 나타납니다. 즉, 집이라는 공간에서 사회, 문화를 탐구하는 것이라 할 수 있습니다. 아래 그림을 예로 들면 두 개의 집이 연결되어 있습니다. 오른쪽 건물은 1970년대 지어진 것으로 추정되고, 왼쪽 건물은 비교적 현대에 지어진 것 같습니다. 이 두 다른 건물을 아케이트로 연결했다는 점을 탐구하기 시작했어요. 독특한 구조가 어떻게 탄생하게 된 것인지, 이 구조에서 살아가는 사람들의 이야기를요. 이처럼 관찰을 통해 탐구하고 저만의 관점에서 초점을 맞추어, 저만의 해석이나 스토리를 만들어가는 것, 그것이 시각인류학이라고 볼 수 있습니다.

In Europe, the concept of a “house” is something for ‘eternity,’ which reflects the associated social and cultural aspects. In other words, the home becomes a lens through which society and culture can be explored. For example, in the image below, there are two connected houses. The building on the right is estimated to be built in the 1970s, while the one on the left appears to be more modern. I began to investigate why these two different buildings are connected by an arcade. I looked into how this unique structure came to be and the stories of the people living inside. This process of exploration through observation, focusing on my perspective, and creating my own interpretations or narratives is what I would consider visual anthropology.

Q6.

선생님의 작업은 관찰에서 출발하는 것 같습니다.

관찰을 후의 과정은 어떻게 되나요?

Q6.

It seems that your work begins with observation.

What comes after that?

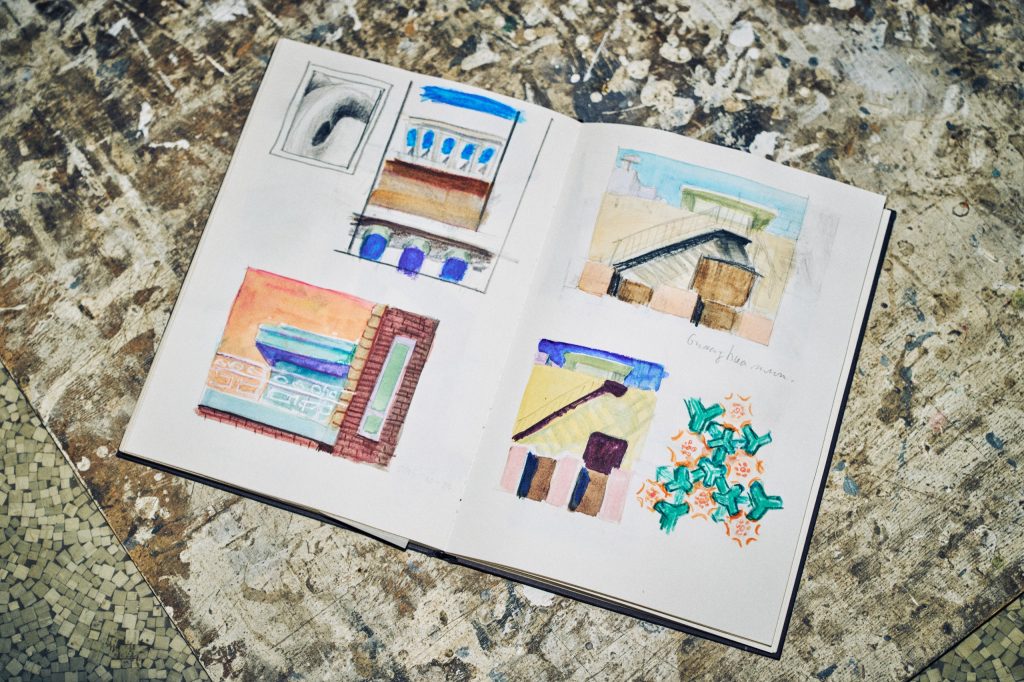

동네 산책을 하며 주택과 건물을 둘러보는데 제 눈길이 닿는 곳의 건물을 발견하면 사진을 찍거나 즉석에서 스케치를 하는 방식으로 자료를 수집합니다. 스케치에서 이미 저의 심미안을 자극하는 포인트를 부각시키죠. 비대칭의 구조나 다양한 건축자재, 색감 등에 초점을 맞춥니다. 작업을 하기 전 실제적 동기가 준 인상이 출발점입니다. 스케치를 바탕으로 이 건축 스타일이 나오게 된 배경을 생각하고, 심미적 표피 속에 숨겨진 의미를 찾는 과정을 거치죠. 두 번째로는 미적 자율성이 구현되는 그림을 그리려고 노력합니다. 물론 스케치를 바탕으로 하지만 그림에서 특정 미적 효과를 얻기 위해 구도와 이미지 디자인의 형식적 아이디어에 따라 비율과 색상 등 세부 사항을 조정하면서 작업을 하지요.

As I walk around neighborhoods, observing houses and buildings, I gather data by taking photos or making quick sketches on the spot when I come across a building that catches my eye. In these sketches, I emphasize elements that stimulate my aesthetic sense, focusing on asymmetrical structures, diverse construction materials, and the color scheme. When I decide to paint a motive, the impression the real motive gave me is the starting point. From these sketches, I begin to think about the background that led to the creation of this architectural style and search for the meanings hidden beneath the aesthetic surface. Second, I try to produce a painting with a certain aesthetic autonomy. While based on my sketches, in order to achieve certain aesthetic effects in my paintings I adjust the proportions, the colors, and the details to the formal ideas of composition and image design.

Q7.

선생님의 그림을 보면 따뜻한 색감이 유독 눈에 띕니다.

색상을 선정하는 기준이 있을까요?

Q7.

Your paintings often feature warm colors that stand out.

Do you have a specific criterion for selecting colors?

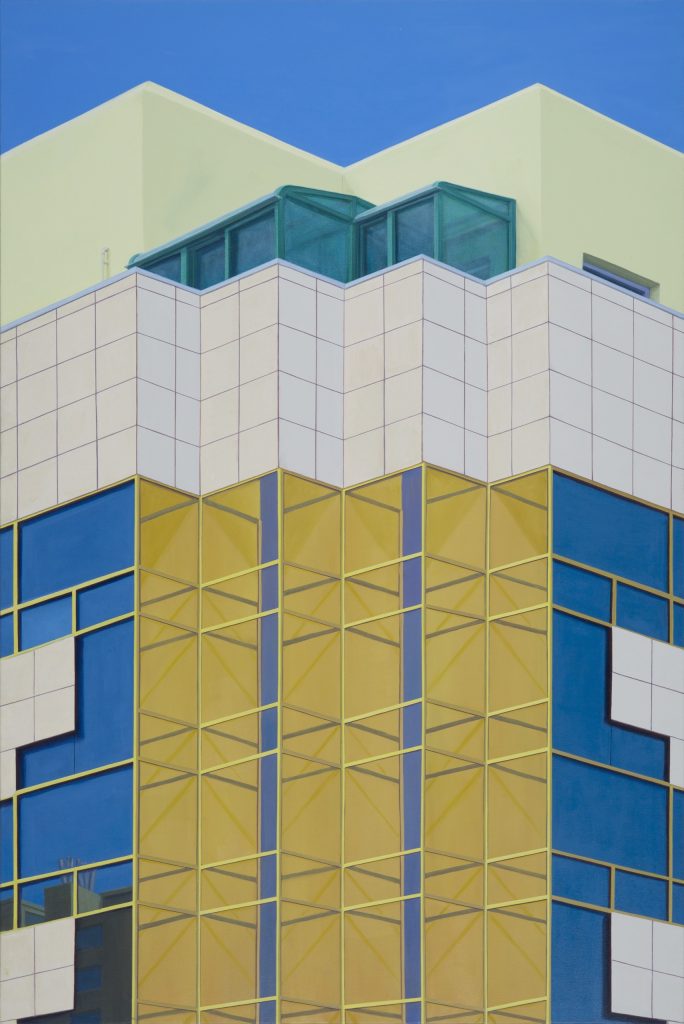

기본적으로 한국의 색을 기반으로 합니다. 한국의 전통적인 색상인 청록색이나 민트, 그린 등이라고 볼 수 있습니다. 한국의 사찰에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 색상인데요. 이 색은 현대 건축 디자인에 여전히 사용되고 있습니다. 제가 본 것을 기반으로 하지만 창작 과정에서 조정되고 수정되어 독자적인 미적 감각을 보여줄 수 있도록 하는 편입니다. 익숙하지만 낯설어 보이는 점을 색상을 통해 찾았을 때 관객들의 몰입도는 극대화됩니다.

I primarily base my color choices on traditional Korean colors, such as turquoise, mint, and green. These are colors commonly seen in Korean temples, and they continue to be used in contemporary architectural designs. While the colors are based on what I see, they are adjusted and modified during the creative process, so that the paintings have their own independent aesthetic effect. And when spectators can recognize things which appear somehow unfamiliar, it is often this shift or difference that attracts and engages them.

#관점

제3자의 눈으로 바라본 한국

#Perspective

Korea seen through the eyes of the 3rd person

Q8.

선생님은 한국 주택에 어떤 한 부분에 초점을 맞춰서 작업을 하는데요.

그것에서 어떠한 미학을 느끼시나요?

Q8.

You focus on certain aspects of Korean houses in your work.

What kind of aesthetics do you find in that?

제가 본 주택이나 빌딩을 재구성하여 화폭에 옮기는 과정에서 유희적이고, 창조적인 아름다움을 즐길 수 있고, 그 과정에서 집의 변화를 포착하게 됩니다. 이 지점이 저에겐 한국의 주택과 빌딩의 미학으로 다가옵니다. 가령 발코니나 테라스 외부 공간을 실내 공간으로 들여놓는 방식이나, 주택의 소유자에 따라 여러 가구가 쪼개지거나 앞서 설명했듯 서로 다른 집이 연결되는 것들. 그러한 변화의 발견이 주는 미학이라고 말하고 싶어요.

For me, in the process of reconstructing the houses or buildings I’ve seen and transferring them onto the canvas, I enjoy a playful and creative beauty, while also capturing the changes that occur in the houses. This, for me, is the aesthetic of Korean houses and buildings. For instance, the way outdoor spaces, like balconies or terraces, are brought into the interior, or how multiple units within a house are divided depending on the inhabitant or as I mentioned earlier, how different homes are connected together. I would say it’s the aesthetics found in the discovery of such changes.

Q9.

선생님이 살았던 유럽과 한국의 문화적 차이는 당연할 것 같습니다.

건축학적인 관점에서 볼 때 어떤 차이점이 있을까요?

Q9.

There certainly must be cultural differences

between the Europe you lived in and Korea.

What are the differences from an architectural perspective?

독일도 전쟁으로 여러 집이 무너지면서 빌딩들을 많이 지었습니다. 그런데 한국과의 차이점이라면 독일에서 지은 빌딩은 한 번 지으면 평생 있어야 하는 관점에서 접근한다는 점이에요. 심지어 저희 가족이 살았던 집은 콜럼버스가 아메리카 대륙 항해를 나가기 2년 전에 지어진 집이었고, 제가 살았던 베를린의 집도 1906년도에 지어졌죠. 이러한 점 때문에 여러 규제가 생겨나고 건물을 허물거나 고치기 어려운 환경이 되었습니다. 주택이나 건물들의 역사적인 가치가 보존되는 반면 변화가 많지 않지요. 역동적인 변화가 많은 한국과 극명하게 대조되는 지점이에요.

Germany has also built many buildings due to the destruction of houses during the war. However, the difference with Korea is that in Germany, buildings are approached with the perspective that once they are constructed, they should be standing there forever. In fact, the house my family member lived in was built two years before Columbus set sail for the Americas, and the house I lived in Berlin was constructed in 1906. Because of this, numerous regulations have emerged, making it difficult to demolish or alter buildings. While the historical value of houses and buildings is preserved, there isn’t much change. This stands in sharp contrast to the dynamic changes taking place in Korea.

Q10.

한국의 역동적인 변화에 대해서

어떤 관점을 견지하고 계시나요?

Q10.

What perspective do you hold

regarding the dynamic changes in Korea?

한국도 독일 환경과 비슷합니다. 전쟁 등으로 건물들이 많이 파괴되었고, 건물을 다시 세우는 과정들이 있었습니다. 특히 저의 화폭에 담긴 주택들은 경제 부흥기 때 지어진 건물들인데요. 이 건물들은 시간이 지나면서 차츰 새로운 집과 빌딩들로 변화했어요. 이러한 역동성은 혁신과 발전을 가져오는 동시에 ‘새로운 것’에 공간을 제공하지만 오래된 미학이 파괴되는 양면성이 존재합니다. 거대한 변화가 사회적, 문화적 정체성의 뿌리가 훼손되는 부정적 측면이지요. 전통적인 부분, 혹은 역사의 흔적이 사라진다고 해야 할까요?

Korea is similar to the environment in Germany. Many buildings were destroyed due to wars, and there have been processes of rebuilding. The houses captured in my paintings were constructed during the period of economic revival, and over time, these buildings have gradually transformed into new houses and buildings. While this dynamism brings innovation and progress, providing space for the ‘new,’ it carries a duality where the old aesthetics is destroyed. A massive change acts as the negative aspect that undermines the roots of social and cultural identity. Perhaps we could say that traditional elements or traces of history are disappearing?

Q11.

변화라는 것에 양면성을 이야기하셨는데요.

변화가 어려운 유럽의 집과 한국의 집에 차이점은 무엇일까요?

Q11.

You’ve mentioned the duality of change.

What are the differences between houses in Europe,

where change is difficult, and those in Korea?

한국은 인구 밀집도가 높은 데다, 집값도 비싸기 때문에 주택으로 지어지기보다는 아파트로 편리성을 추구할 수밖에 없다고 생각합니다. 실제로 아파트의 구조가 편리하잖아요. 반대로 변화가 없는 유럽의 예를 들어 볼게요. 프랑스도 건물을 철거하려면 허가가 필요하기 때문에 대부분 내부적으로 리모델링을 많이 하는 편입니다. 그런데 파리에 거주하는 제 친구의 아파트는 문을 열면 안방이고, 그 안방을 통해 화장실과 주방으로 가는 독특한 구조로 되어 있습니다. 예전 건물을 그대로 놔두고 내부만 고치면서 일어난 폐해인 거죠.

In Korea, due to high population density and expensive housing prices, there is a tendency to pursue convenience through apartments rather than to build a house with a garden. The layout of apartments is indeed quite practical. On the other hand, let me give you an example from Europe, where change is minimal. In Paris / France the demolition of old buildings from 19th century and earlier is difficult because old buildings are seen as historical monuments as well. So it is quite common to remodel the interior of the building. For instance, my friend’s apartment in Paris has a unique layout where opening the door leads directly into the bedroom, from which you access the bathroom and the kitchen. This is the damage that occurred when the old building was left as is and only the interior was renovated.

Q12.

우리의 뿌리를 훼손시키는 측면이 있다고 말씀하셨는데,

한국의 이상적인 건축물을 꼽는다면 무엇이 있을까요?

Q12.

You said that there are aspects that undermine our roots.

If you were to name an ideal architectural structure in Korea,

what would it be?

이상적인 건축물을 꼽는다면 세종문화회관을 이야기하고 싶습니다. 한국의 근대화와 전통성을 절묘하게 조합했다고 생각하기 때문입니다. 이런 부분들이 잘 유지가 돼서 사라지지 않고 오래도록 보존되었으면 합니다. 저의 작은 바람이라면 한국의 재개발 등이 무에서 유를 창조하기보다는 유에서 유를 다시 창조하는 방식이길 바랍니다. 그렇다면 한국의 전통적인 측면을 유지하면서도 새로운 변화를 추구할 수 있지 않을까 해요.

I would name the Sejong Center for the Performing Arts. I think it exquisitely combines modernity and tradition in Korea. I hope that such aspects are well preserved and not lost over time. My small wish is for redevelopment in Korea to focus on recreating from what already exists rather than creating something entirely new. I believe this way, it will allow us to maintain our traditional aspects while still pursuing new changes.

#소통

시각적인 언어의 대화

#Communication

A conversation through visual language

Q13.

선생님은 한국의 양면성, 한국인이 캐치하지 못한 점들을

화폭에 담고 계시는데,

관객이 어떠한 부분에서 어떠한 점을 느꼈으면 하시나요?

Q13.

You capture the duality of Korea and aspects

that often go unnoticed by Koreans in your paintings.

What do you hope the audience feels

when viewing your work?

한국인이 제 그림을 볼 때 추억이나 경험을 떠올릴 것 같습니다. 주로 1970~1990년대 주택을 담고 있기 때문이죠. 하지만 제가 본 것을 그대로 담지 않기 때문에 제 작품을 감상하는 관객들이 먼저 색과 비율, 조화와 긴장감을 즐기고, 공유된 현실에 대한 저의 다른 시각을 인식하고 자신의 시각을 다시 돌아봤으면 합니다. 새로운 작품이 탄생할 때마다 예술가는 조금씩 성장하는데, 새로운 작품이 지식과 경험의 영역을 넓혀주기 때문입니다. 관객도 예술 작품을 감상하면서 지식과 경험의 영역이 확장될 수 있다고 생각해요. 이렇게 예술은 사회적 결속력과 문화적 정체성을 강화할 수 있습니다. 예술적 소통의 과정이 잘 작동하여 사회 발전에 긍정적인 영향을 미쳤으면 좋겠습니다.

When Koreans look at my paintings, I think they will be reminded of memories or experiences, especially since I often depict houses from the 1970s to 1990s. However, since I don’t replicate exactly what I see, I wish that spectators of my work first enjoy the colors and proportions, the harmony and the tensions of the composition and that then they become aware of my different view upon the shared reality and start rethinking their own views. With every new piece of art, the artist grows a little bit, because that new work is expanding his or her spheres of knowledge and experience. When spectators get engaged with artworks, their spheres of knowledge and experiences expand too, and this way, art can strengthen the social cohesion and cultural identity. I hope that those processes of artistic communication will function well and that they will have positive effects on the development of society.

Q14.

선생님이 말씀하신 이야기의 맥락을 짚어보면

시각적 언어를 통한 관객과의 소통이라고 봐도 될까요?

Q14.

Would it be appropriate to interpret your words

as communicating with the audience

through visual language?

그럴 수 있을 것 같아요. 소통의 매개체는 언어인데, 저는 한국어를 잘하지 못하기 때문에 제가 그린 그림으로 소통한다고 볼 수 있습니다. 그런 측면에서 시각적 언어로 소통한다고 이야기할 수 있습니다. 그림을 그리는데도 한국어를 못하는 부분은 긍정적인 영향을 줍니다. 중간적인 입장을 견지하면서 사물을 바라볼 수 있기 때문이죠. 그런 면에서 한국인이 놓치는 것들을 중간적인 입장에서 관찰하고 발굴한다고 생각합니다.

Yes, I believe so. Language is the bridge for communication, but since my interaction with Koreans is limited due to my lack of language, I consider my paintings as my way of connecting with people. In that sense, it can indeed be described as communicating through visual language. Interestingly, my lack of fluency in Korean has had a positive influence on my creative process. It allows me to maintain a more neutral in-between perspective, giving me a unique vantage point to have a different view upon things. From this position, I believe I can discover and highlight aspects that Koreans themselves may overlook.

Q15.

앞으로 선생님은 어떠한 목표로 작업을 하며,

학생들에게는 무엇을 가르치실 계획인가요?

Q15.

What are your future goals for your work,

and what do you plan to teach your students?

학생 시절부터 저는 우리 모두가 공유하는 현실을 언급함으로써 제 작품이 저와 관객 사이에 연결고리를 만드는 것을 목표로 삼았어요. 그것은 제가 결코 포기하고 싶지 않은 목표입니다. 그 목표를 바탕으로 창의적인 과정을 즐기면서 계속 그림을 그리며 관객과 소통하고 싶습니다. 또한 학생들을 가르치는 일은 무척 흥미로운 일인데요. 창의적인 작업을 위한 기본이 되는 지적 능력, 손기술, 감각을 학생들이 개발하길 바라는 만큼 그 부분에서 집중하고 싶습니다.

Since my student days, I aimed to create a connection between me (my perception) and the spectators through my work by referring to the reality we all share. That is something I do not want ever to abandon. Based on that goal, I want to continue painting and communicating with my audience, all while enjoying the creative process. Teaching students is also something I find very exciting. In university, I want to focus on helping students to develop their intellectual, manual-technical and sensual skills, which are all basics for creative work.

잉고 바움가르텐 Ingo Baumgarten

1964년 독일 서부 하노버 출생하여 독일, 영국, 프랑스, 일본에서 미술 교육을 받았다. 독일, 포르투갈, 프랑스, 일본, 대만, 미국, 한국, 중국, 호주에서 전시 활동을 해왔으며, 2008년부터 서울에서 거주하면서 한국의 주택을 화폭에 담고, 홍익대학교에서 미술을 가르치고 있다. 《잉고 바움가르텐: just painting》 , 《住宅 (주택)》 등 다양한 전시를 진행하고 있다. 최근에는 2023년 전시를 개최한 바 있다.

Ingo Baumgarten

Born in 1964 in Hanover, West Germany, Ingo Baumgarten received art education in Germany, the UK, France, and Japan. He has exhibited his works in Germany, Portugal, France, Japan, Taiwan, the United States, Korea, China, and Australia. Since 2008, he has been living in Seoul, capturing Korean houses on canvas and teaching art at Hongik University. He has held various exhibitions, such as Ingo Baumgarten: Just Painting, Space & Color, Urban Details, and 住宅 (House). Recently, in 2023, he held the exhibition Compromises.

Epilogue

이날의 취재는 그의 교수실이자 작업실에서 이루어졌다. 언뜻 보기엔, 어느 대학에서나 볼 법한 교수실의 정사각형 구조다. 하지만 그의 그림을 보듯 익숙하면서도 낯선 풍경에 매료된다. 창문 한편을 차지한 식물들은 멋대로 뻗어 있었지만 자연스럽게 녹아들어있었고, 대형 캔버스와 형형색색의 물감이 담긴 팔레트와 칠하다 만 붓은 화가의 작업실을 연상케 했으며, 홍익대학교 연못에서 이사해 온 물고기와 두서없이 쌓인 책들, ‘프림’을 넣어서 먹는다는 커피와 커피메이커는 그의 취향을 짐작게 했다. 마치 한국 주택이 익숙하면서 낯선 구도로, 평범하지만 이국적인 색감으로 화폭에 담겨 있듯, 잉고 바움가르텐은 한국의 정형화된 교수실을 그의 관점에서 새롭게 해석해 놓았다. 그래서 이날 취재를 하며 ‘공간’이란 무엇을, 어떻게 담느냐에 따라 같지만 같지 않을 수 있음을 깨닫게 되었다.

Epilogue

The interview took place in his office and studio. At first glance, it had the square structure typical of any university professor’s office. Yet, much like his paintings, the space captivated me with a mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar. The plants occupying one corner of the window grew wildly, yet blended in naturally. The large canvases, palettes filled with vibrant paints, and brushes left mid-stroke evoked the atmosphere of an artist’s studio. Fish relocated from the pond at Hongik University, books piled haphazardly, and a coffee maker and coffee complemented by creamer, gave insight into his personal tastes. Just as Korean houses appear familiar yet foreign in his paintings, with their ordinary yet exotic color palettes, Ingo Baumgarten reinterpreted the conventional Korean professor’s office from his own perspective. This interview made me realize that a “space” can contain and express the same elements in ways that feel both similar and entirely different, depending on how it is presented.