손끝으로 짓는 울림 외국인 최초 가야금 이수자 – 조세린

Resonance at Her Fingertips Jocelyn Clark, the First Foreign Heir of Gayageum Sanjo

Localler

새롭게 떠오르는 문화를 발견해 융합해 나가는 ‘문화의 선구자 Culture Vanguard’ 역시 기아 디자인 크리에이티브 철학의 문화적 특징 중 하나입니다. 기아디자인매거진은 Localler라는 메뉴를 통해 ‘문화의 선구자 Culture Vanguard’라는 타이틀로 한국에서 살고 있는 현지 외국인, 외국에서 살고 있는 현지 한국인들의 경계 없는 스토리를 보여줍니다.

Localler

As a Culture Vanguard, who discovers and integrates emerging culture, is another feature of Kia Design’s creative philosophy. In the Localler menu, Kia Design Magazine presents stories about foreigners living in Korea, as well as Koreans living abroad, under the title ‘Culture Vanguard’.

한국에 처음 온 한 외국인이 가야금의 첫 줄을 튕기던 순간, 말보다 먼저 울림이 번졌습니다. 그녀와 한국 사이에는 새로운 언어가 피어났고, 그 시작은 설렘이었지만 시간이 흐르며 숙명이 되었습니다. 긴 세월 끝에 그녀는 ‘가야금 산조’ 무형문화재 이수자가 되었습니다. 단순히 자격을 얻었다고 말하기에는, 그 과정이 담고 있는 이야기가 너무 깊습니다. 그녀는 몸으로 장단을 익히고, 감정으로 음을 새기며 한국 문화 속에 천천히 스며들었습니다. 배움을 넘어, 이제는 한국의 일부가 된 사람의 기록은 오늘도 조용히 이어집니다. 《기아 디자인 매거진》 VOL.15 ‘Localler’에서는 전통이 과거에 머무는 것이 아니라, 지금도 살아 숨 쉬며 미래로 이어질 수 있음을 보여주는 조세린 교수의 이야기를 전합니다.

When a foreigner in Korea plucked the first string of a gayageum, sound traveled before words could. Between her and Korea, a new language began to bloom. At first it was simple wonder, but over time it became destiny. After many years she was recognized as a bearer of the sanjo tradition, inheriting the lineage of intangible cultural heritage. To call it merely a qualification would overlook the depth of her journey. She learned rhythm with her body, carved tones with emotion, and gradually immersed herself in Korean culture. Beyond learning, she has become part of Korea itself, and her record continues quietly today. In Kia Design Magazine Vol.15 Localler, we share the story of Professor Jocelyn, whose path shows that tradition does not remain in the past but lives on in the present and carries forward into the future.

- 이수자의 도전,

자신이 걸어온 길을 증명하다 - 가사 없는 판소리,

가야금 소리의 맛을 깨닫다 - 전통문화는

마르지 않는 우물이다 - 이수자로서의 사명감을

지키기 위한

- An Heir’s Challenge,

Affirming the Journey She Has Made Her Own - Pansori Without Words,

Awakening to the Gayageum - Tradition Flows

From a Well That Never Runs Dry - The Responsibility of an Heir

to Tradition

Editor’s Note

익숙한 탓에 우리가 놓치고 지낸 아름다움을, 전혀 다른 자리에서 발견해 자신만의 언어로 이어가는 이들이 있습니다. 조세린 교수가 바로 그중 한 사람입니다. 1992년, 낯선 땅에 발을 디딘 그녀는 처음 들은 가야금 소리에 감흥을 느끼지 못했다고 합니다.

아직 귀가 열리지 않았던 탓이죠. 그러나 손끝으로 장단을 익히고, 몸으로 음을 새기는 시간이 쌓이면서 가야금의 소리는 서서히 그녀 마음속에 스며들었습니다.

그녀의 연주는 단순한 소리의 구분을 넘어, 문화를 받아들이는 태도이자 마음 깊은 곳에서 우러난 진심의 표현입니다. 전통은 그저 이어받는 것이 아니라, 오랜 시간과 애정을 쌓아야 비로소 ‘내 것’이 됩니다. 그 길 위에서 국적은 아무런 장벽이 되지 않습니다. 조세린 교수의 여정은 외국인의 특별한 경험을 넘어, 우리가 익숙함 속에서 잊고 지냈던 한국의 또 다른 얼굴을 비춥니다. 그녀의 손끝에서 되살아난 가야금의 소리는, 어쩌면 우리가 가장 순수하게 지켜야 할 한국의 소리일지도 모릅니다.

《기아 디자인 매거진》 VOL.15 ‘Localler’에서는 조세린 교수와 가야금이 함께 걸어온 시간을 따라가며, 전통을 대하는 우리의 태도에 대해 다시금 깊이 생각해봅니다.

Editor’s Note

Some rediscover the beauty we take for granted,giving it new life in a language uniquely their own. When she Jocelyn first set in Korea in 1992, the sound of the gayageum did not move her. Her ears were not open yet. But as time passed, as she practiced rhythm through her fingertips and absorbed melody with her body, the sound of the instrument slowly settled into her heart. Her playing is more than the arrangement of notes. It is an attitude toward a way of receiving culture, an expression of sincerity that rises from deep within. Tradition is never something one inherits passively. It becomes one’s own only after years of devotion and care. On that path, nationality holds no barrier.

Jocelyn’s journey is not simply a foreigner’s unusual encounter. It reflects back to us another face of Korea, one we may have forgotten in the comfort of our own familiarity. The sound of the gayageum revived in her hands may well be the very sound of Korea we must preserve in its purest form. In Kia Design Magazine Vol.15 Localler, we follow the journey of Professor Jocelyn and the gayageum, and reflect on what it means to truly embrace tradition.

Chapter 01.

이수자의 도전, 자신이 걸어온 길을 증명하다

Chapter 01.

An Heir’s Challenge, Affirming the Journey She Has Made Her Own

2025년 봄, 조세린 교수가 전라북도 무형문화재 제41호 ‘가야금 산조’ 부문 이수자로 선정되었다. 외국인으로서는 처음 있는 일이었다. 그러나 그녀는 ‘최초’라는 말보다 이 자리에 닿기까지의 시간과 마음에 더 큰 의미를 둔다. “정말 오랜 시간이 걸렸습니다. 돌이켜보면, 제게는 삶의 한 시기를 고스란히 바친 결과였습니다.” 처음부터 가야금에 마음을 뺏긴 건 아니었다. 가야금 연주를 들었지만 마음은 움직이지 않았다. “그때는 제 귀가 아직 닫혀 있었던 거예요. 그냥 낯설고 생소한 소리였어요.” 가야금의 매력을 알지 못했던 그녀가 한국을 떠나지 않고 배움을 이어간 데에는 탐구 정신이 자리했다. 중국의 쟁과 일본의 고토クトゥ를 배운 경험이 있었기에, 세 악기의 차이점이 궁금했던 것. 그러다 장단을 손끝으로 익히고, 감정을 몸으로 새기며 낯설었던 소리의 깊이를 차츰 알게 되었다.

그렇게 깨달은 가야금의 매력은 결국 이수자 시험 도전으로 이어졌다. 그러나 그 시험은 단순한 기량만으로는 넘기 어려운 벽이었다. 일곱 가지 장단을 즉흥적으로 엮어 연주해야 했고, 해석과 이론까지 종합적으로 평가받아야 했다. 그녀는 그 시간을 “전통을 나만의 언어로 다시 쓰는 과정”이었다고 말한다.

In the spring of 2025, Professor Jocelyn was named a designated trainee (isunja) in the Gayageum Sanjo category, the 41st Cultural Property of Jeollabuk-do. She was the first foreigner to receive such recognition. Yet for her, the meaning lay less in being the “first” and more in the years of devotion it had taken to reach at this point.

“It took a very long time,” she recalls. “Looking back, it feels as though I gave an entire season of my life to this journey.” It was not love at first sound. When she first encountered the gayageum, her heart remained unmoved.

“My ears simply weren’t open yet. To me it was only an unfamiliar, foreign sound.”

What kept her in Korea, continuing to learn despite that distance, was her spirit of inquiry. Having studied the Chinese zheng and the Japanese koto, she was curious about how the three instruments differed. Gradually, as her fingertips absorbed the rhythms and her body imprinted the emotion of each note, she began to sense the depth within what once seemed alien. That realization eventually led her to take on the challenge of the official isunja examination. But the test was a formidable barrier, one that demanded far more than technical skill. She had to weave together seven rhythmic cycles in improvisation, while also demonstrating mastery of interpretation and theory. For her, the process became, as she describes it, “a way of rewriting tradition in my own language.”

“정해진 곡을 그대로 연주하는 것이 아니라, 제가 살아온 방식으로 장단을 풀어내야 했습니다. 그 안에서 제가 어떤 감각을 품고 살아왔는지를 마주하게 되었죠.” 시험장에 들어서는 순간, 수십 번의 무대보다 더 깊은 긴장감이 밀려왔다. 그 자리는 한국에서 보낸 30년이 자신 안에 얼마나 살아 있는지를 확인하는 시간이었고, 그동안 배운 것들이 진짜였는지를 조용히 묻는 자리이기도 했다. 시험이 끝난 뒤 찾아온 기다림은 의외로 고요했고, 마음 한켠은 평화로웠다.

“기다림조차 연주의 일부처럼 느껴졌어요. 산조의 장단은 긴장과 이완이 교차하며, 그 흐름 속에서 완성되거든요. 제 삶도 그와 비슷했던 것 같아요.”

조급함 대신 흐름을, 불안 대신 리듬을 떠올리며 시간을 보냈고, 마침내 ‘이수자’라는 타이틀을 얻었다. 그것은 단순한 자격이 아니라, 자신이 이 음악을 얼마나 사랑해왔는지를 증명하는 일이었다. “이수자라는 말 안에는 그 소리를 지켜가겠다는 다짐이 담겨 있어요.”

그녀에게 이수자 도전은 어쩌면 너무도 자연스러운 선택이었다. 0여 년간 가야금과 함께하며 한국 전통음악의 깊이를 파고들었고, 그 울림 속에서 자신만의 길을 다져왔다. 이처럼 조세린 교수는 외국인이라는 경계를 넘어 진정한 실력을 입증하고, 자신만의 정체성과 여정을 확립하기 위해 이수자 시험에 도전한 것이다. 이수자로 선정된 그녀는 외국인도 한국 문화에 진정으로 스며들 수 있음을, 자신의 삶과 연주로 증명해 보였다.

“It was not about performing a set piece exactly as written. I had to unfold the rhythms in the way I had lived, to face the sensibilities I have carried within me.”

The moment she entered the examination room, a tension deeper than dozens of performances washed over her. It was not only a test but a reckoning, a time to see how much of her thirty years in Korea had truly become part of her, and whether all she had learned was real. When it was over, the waiting that followed felt unexpectedly calm, almost peaceful.

“Even the waiting felt like part of the performance. Sanjo is completed through a flow of tension and release, and my life has been much the same.” She remembered not impatience but flow, not anxiety but rhythm. In the end she earned the title of designated trainee. For her, it was not simply a qualification but a testament to how deeply she had come to love this music.

“Within the word isunja lies a vow to preserve the sound.”

For Jocelyn, becoming an isunja was a natural step. After decades with the gayageum, immersing herself in the depth of Korean traditional music, she had built her own path within its resonance. By taking the examination, she not only proved her skill beyond the boundary of being a foreigner but also affirmed her own identity and journey. Her recognition as an isunja stands as proof that even those from outside Korea can truly become part of its culture, both in life and in performance.

Chapter 02.

가사 없는 판소리, 가야금 소리의 맛을 깨닫다

Chapter 02.

Pansori Without Words, Awakening to the Gayageum

1992년, 조세린이 서울에 처음 도착했을 때, 한국은 낯설고 불편했다. 언어만 조금 배운 채였고, 어떤 나라인지, 어떤 문화가 있는지, 어떻게 살아가야 하는지도 알지 못했다.

“한국이 지금처럼 K-팝이나 드라마로 알려진 시대가 아니었어요. 가야금을 배우겠다고 마음먹고 왔지만, 막상 와보니 머무를 곳조차 없었어요. 월세, 전세 같은 개념도 이해하지 못했었죠.”

When Jocelyn first arrived in Seoul in 1992, Korea istant and disorienting She knew a little of the language, andalmost nothing about the country, its culture, or daily life.

“Korea was not yet known through K-pop or dramas the way it is today. I came with the intention of studying the gayageum, but once I arrived, I realized I did not even have a place to stay. I could not understand the concepts of monthly rent or jeonse at all.”

그렇게 시작한 한국 생활은 서울대학교에서 박칼린을 알게 되면서, 안정을 찾아갔다. 이후 조세린 교수는 학교에서 민요와 정악, 병창 등을 익히며 전통음악의 기반을 다져갔다. 정악은 김천흥 선생에게, 병창은 이은관 선생에게, 가야금 산조는 전라북도 무형문화재 제41호 보유자인 강정숙 명인에게 사사했다. 그 배움의 시작에는 분명 “한국 생활이 어려웠다”고 말하던 낯섦이 있었지만, 그 시간을 지나며 그녀는 점차 소리에 마음을 기댈 수 있게 되었다고 말한다.

“손에 피가 나기도 했어요. 박자도 익숙하지 않았습니다. 서양 음악은 대부분 4박인데 한국 장단은 3박 위주라 처음에는 어렵게 느껴졌죠.”

그녀는 민요로 시작해 정악, 산조까지 배우며 음악의 스펙트럼을 확장해 갔다. 단순히 기술을 익히는 것이 아니라, 전통음악이 가진 ‘맛’을 알아가는 과정이었다. 정악은 마음을 다잡고 절제된 자세로 연주해야 했고, 산조는 흘러가는 감정을 그대로 실어내야 했다. 악보로 배운 정악과 다르게 산조는 녹음을 통한 구슬 수업이 중심이었고, 그 차이에서도 전통의 깊이를 느낄 수 있었다고 회상했다.

이쯤 되니, 왜 그녀가 가야금에 그토록 몰두하는지 궁금해진다. 처음부터 그 소리에 매료된 것은 아니었다. 그러나 어느 순간부터 가야금이 내는 ‘소리의 맛’을 알아버렸다. 그녀를 사로잡은 건 가야금만의 공명이었다. 줄 하나하나에서 울려 퍼지는 소리가 겹겹이 번져나가며 마음 깊은 곳을 흔들었다. 이전에는 어떤 악기에서도 느껴보지 못했던 경험이기 때문이다. 그 맛이 어떤 것이냐는 질문에, 그녀는 먼저 자신이 배웠던 고토와 쟁을 꺼내 비교해 이야기해줬다. 세 악기는 줄의 수, 음계, 연주 방식에서 다르다. 고토와 쟁은 피크를 써서 손톱을 대지 않고 연주하지만, 가야금은 손가락으로 직접 줄을 튕겨야 한다.

“고토나 쟁은 음량이 크고 직선적인 선율을 가지고 있어요. 반면 가야금은 줄 하나를 울리기 위해 나머지 줄을 막아야 해요. 그만큼 소리의 섬세함이 담기죠.”

“고토나 쟁은 음량이 크고 선율이 직선적으로 뻗어나가요. 하지만 가야금은 한 줄을 울리기 위해 다른 줄을 막아야 하죠. 그만큼 소리에 섬세함이 스며듭니다.”

가야금은 손과 줄이 직접 맞닿는 악기입니다. 도구 없이 맨손으로 소리를 내기에, 연주자는 줄의 떨림 속에서 감정을 고스란히 느끼게 됩니다.

“그래서 저는 가야금을 ‘가사 없는 판소리’라고 부릅니다.”

가야금의 음역은 사람의 목소리와 닮았습니다. 높은 음에서 낮은 음까지 자연스럽게 이어지며, 기쁨과 슬픔을 모두 품어낼 수 있죠. 웃는 듯, 우는 듯, 그 사이를 오가는 표현의 폭이 바로 가야금의 매력입니다. 그러나 그녀는 가야금의 진짜 어려움은 따로 있다고 말한다.

“한 번 낸 소리를 끝까지 지켜야 해요. 정확한 울림을 만들기 위해 다른 줄을 막고, 손끝의 떨림으로 마지막까지 소리를 내보내야 하죠.”

그 한 음을 완성하기까지의 집중과 감정. 그녀는 그 과정을 수십 년 동안 몸으로 익혀왔다.

Her life in Korea began to find stability when she met Park Kalin at Seoul National University. There, she laid her foundation in traditional music, studying folk songs, jeongak (court music), and byeongchang (singing with gayageum accompaniment). She trained in jeongak under Kim Chun-heung, in byeongchang under Lee Eun-gwan, and in gayageum sanjo (improvised solo instrumental music) with Kang Jung-sook, the official holder of Jeollabuk-do Intangible Cultural Property No. 41.

Though she often described those early years as “difficult,” she recalls that, over time, sound itself became a place where her heart could rest.

“My hands would sometimes bleed. The rhythms were unfamiliar. Western music is mostly in four beats, but Korean jangdan often flow in three, which was difficult for me at first.”

From folk songs to jeongak and then to sanjo, she steadily expanded her musical spectrum. It was not simply about learning technique but about discovering the flavor of traditional music. Jeongak required discipline and restraint, while sanjo equired the unfiltered flow of emotion. Unlike jeongak, learned through scores, sanjo was passed down orally through recordings, and in that contrast she sensed the depth of tradition.

Why then did she become so devoted to the gayageum? admits it was not fascination at first sound. But at some point she discovered what she calls “the taste of its sound.” What captivated her was its resonance: the way each string sent vibrations rippling outward in layers that shook something deep inside her, an experience she had never felt with any other instrument.

Asked to explain, she compared the gayageum with instruments she had studied before, the Japanese koto and the Chinese zheng. The three differ in the number of strings, tonal range, and playing technique. The koto and zheng are played with picks, while the gayageum is plucked directly with the fingers.

“The koto and zheng produce a larger volume and more linear melodies. The gayageum, however, requires you to mute the other strings for one to resonate, and that delicacy becomes part of its sound.”

Because the gayageum is played with bare hands, every vibration is felt directly through the fingertips.

“That is why I call the gayageum a pansori without words,” she says.

The instrument’s range resembles the human voice, flowing naturally from high to low, able to carry both joy and sorrow. It can laugh, it can weep, and it can dwell in the subtle space in between. Yet she notes that the real challenge of the gayageum lies elsewhere.

“You must sustain each note until its very end. To create a pure resonance, you dampen the surrounding strings and let the sound carry through the tremor of your fingertips.”

The concentration, the emotion contained in a single note—she has spent decades learning this through her body.

Chapter 03.

전통문화는 마르지 않는 우물이다

Chapter 03.

Tradition Flows From a Well That Never Runs Dry

조세린 교수는 현재 배재대학교 주시경교양대학에 소속되어 있다. 학생들에게 한국어와 한국 문화를 가르치면서 연주자이자 기획자로서의 길을 멈추지 않고 걸어왔다.

“공연을 많이 하지는 못했지만 쉬지는 않았어요. 주말이나 방학에는 무대에 서려고 노력했어요.”

가야금 병창, 산조, 정악 등 다양한 레퍼토리를 바탕으로 독주회와 협연 무대를 꾸준히 이어왔으며, 문화센터와 공공기관 등에서 워크숍도 활발하게 열었다. 낯선 이방인의 손끝에서 울려 나오는 전통음악은, 오히려 많은 이들에게 ‘익숙한 것의 새로움’을 선물했다.

“전통을 낯선 사람의 손에서 새롭게 듣는다는 반응이 많았어요. 전통이 꼭 익숙해야만 감동을 주는 건 아니더라고요.”

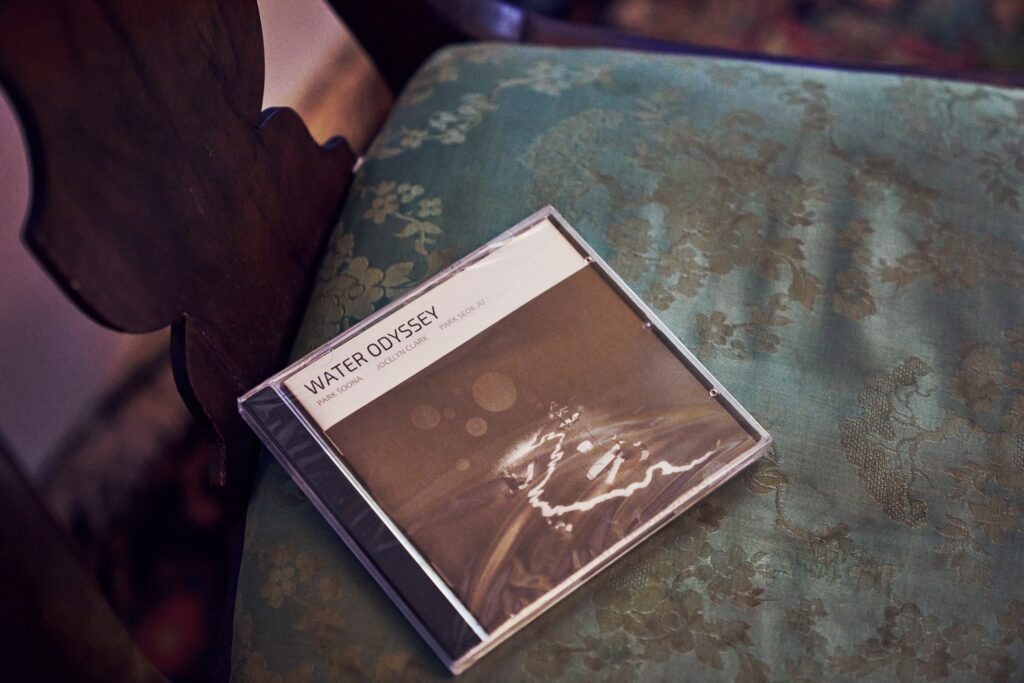

팬데믹 시기에도 그녀의 음악은 멈추지 않았다. 직접 관객을 마주하기 어려운 시기였지만, 오히려 그 시간은 새로운 형식을 시도하는 계기가 되었다. 그녀는 가야금 연주자 박순아, 기타리스트 박석주와 함께 ‘Water Odyssey(생명의 여정)’이라는 앨범을 제작했다. 즉흥 연주로 만든 5곡을 담았지만, 공연에서는 한 시간 동안 하나의 흐름으로 이어져 연주되었다. 그녀에게 이것은 전통을 실험하고 확장하는 새로운 자극이었다.

“힘든 시기였지만, 오히려 우리 안에 깊이 잠겨 있던 소리를 정리하고 꺼내보는 시간이었어요. 장단을 맞추고, 해석을 나누고, 서로의 숨을 듣는 작업이었죠.”

2009년, 배재대학교 교수로 부임한 이후 그녀의 음악 여정에 또 하나의 전환점이 찾아왔다. 국악 전문 음반사 악당이반으로부터 가야금 산조 앨범 제작 제안을 받았다. 처음엔 대수롭지 않게 흘려보냈지만, 1년 뒤 다시 걸려온 전화. “준비하고 있나요?”라는 짧은 물음이 그녀의 마음을 단단히 붙잡았다. 그것은 단순한 제안이 아니라, 외국인인 그녀가 전통음악 속으로 더 깊숙이 뛰어들도록 등을 떠민 운명 같은 신호였다. 그 후 끊임없는 연습 끝에 조세린 교수는 9월에 산조 앨범 녹음을 앞두고 있다. 그녀가 사사한 강정숙 명인의 산조를 온전히 담아내는 이번 작업은 단순한 음원 기록이 아니라, 하나의 증명이다. 한국 전통의 맥을 이어받은 외국인 연주자가 남기는 ‘음악적 족보’이자, 그 진심을 증명하는 자리다.

왜 이런 시도를 하느냐는 물음에 그녀는 ‘전통의 우물’ 이야기를 꺼냈다.

“전통은 고여 있는 물이 아니라, 계속 길어 올려야 하는 깊은 우물이에요. 저는 그 우물에서 길어 올린 물을 제 방식으로 전하고 싶어요. 그리고 그 물이 다음 세대에게도 이어졌으면 합니다.”조세린 교수가 말하는 ‘전통의 우물’은 단순한 비유가 아니다. 그것은 그녀가 지난 수십 년간 몸으로 느끼고, 마음으로 체득해온 한국 전통문화에 대한 정의이기도 하다.

“사람들은 종종 전통이 고갈된 것처럼 느끼는 것 같아요. 하지만 그건 전통의 뿌리를 제대로 들여다보지 않기 때문이라고 생각해요. 전통은 마르지 않는 우물이에요. 우리가 자꾸 겉에서만 물을 퍼내려 하니까, 마르는 것처럼 보이는 거죠.”

Today, Professor Jocelyn teaches at Paichai University’s Joo Si-gyeong College of Liberal Arts, while continuing her path as both performer and curator.

“I haven’t been able to perform as often as I wished, but I never stopped. On weekends or during breaks, I always tried to step onto the stage.”

With a repertoire spanning byeongchang, sanjo, and jeongak, she has steadily presented solo recitals and collaborations, as well as workshops in cultural centers and public institutions. From the fingertips of a foreigner, traditional Korean music came alive in a way that felt unexpectedly new, gifting audiences with what she calls “the unfamiliarity of the familiar.”

“People often told me that hearing tradition through the hands of someone foreign made it feel new. Tradition does not need to be familiar to move us.”

Even during the pandemic her music did not stop. Though facing audiences in person was difficult, that time became an opportunity to experiment with new formats. Together with gayageum player Park Sun-a and guitarist Park Seok-joo, she produced Water Odyssey, an album of five improvised pieces performed in concert as a single continuous flow. For her, it was a powerful stimulus, a way to test and expand the boundaries of tradition.

“It was a hard time, but it gave us the chance to bring out sounds that had long been buried deep inside. We adjusted rhythms, shared interpretations, and listened for each other’s breath.”

Since joining Paichai University as a professor in 2009, another turning point arrived. The record label Akdang Iban, specializing in Korean traditional music, invited her to produce a gayageum sanjo album. At first she brushed it aside, but a year later the phone rang again with a simple question: “Are you preparing?” That brief call struck her like fate. urging a foreign musician to plunge even deeper into tradition. Now, after years of relentless practice, she is preparing to record the sanjo album this September. The work will faithfully embody the sanjo lineage of her teacher, master Kang Jung-sook, holder of Jeollabuk-do Intangible Cultural Property No. 41. But for Jocelyn it is not merely a recording. It is a testimony: a musical genealogy preserved by a foreign performer who has inherited the Korean tradition, and a proof of sincerity carried in sound.

When asked why she takes on such challenges, she returns to the image of a well.

“Tradition is not stagnant water. It is a deep well we must keep drawing from. I want to share the water I draw in my own way, and I hope it flows on to the next generation.”

For Jocelyn, this metaphor is no ornament It is the essence of a life lived with and within Korean traditional culture.

“People sometimes think tradition has dried up. But that is because they look only at the surface. Tradition is a well that never runs dry. If we keep drawing only from the shallow edges, it may seem empty. But the deeper we reach, the more inexhaustible it becomes.”

그녀가 말하는 ‘겉’이란, 흉내 내듯 재현하는 연주, 기술로만 따라가는 음악, 또는 피상적인 이해에 머무는 태도다. 그런 접근만으로는 전통의 깊은 정서나 울림을 만날 수 없다. 그래서 조세린 교수는 더 깊이 내려가야 한다고 말한다. 마치 우물을 깊이 파야만 진짜 맑은 물을 만날 수 있는 것처럼.

“깊이 내려가면, 그 안에는 여전히 맑고 풍부한 물이 흐르고 있어요. 그 물은 지금도 생생하고, 지금 이 시대에도 충분히 마실 수 있는 물이에요. 전통도 그래요. 우리가 진심으로 다가가면, 전통이란 새로운 감각과 울림을 주죠.”

그녀의 산조 녹음은 깊은 우물에서 길어 올린 한 바가지의 물과 같다. 오래 고인 물이 아니라, 여전히 맑고 살아 있는 물. 과거의 소리가 아니라, 지금 이 순간 그녀의 손끝과 마음에서 다시 깨어난 전통의 숨결이다. 조세린 교수는 이 우물의 깊이를 믿으며, 그 안에 담긴 생명의 물을 다음 세대에게 건네고자 한다. 그리고 바로 이 우물이 있어야 전통의 대중화와 세계화가 가능하다고 믿는다.

What Jocelyn means by the “surface” is performance that only imitates, music bound technique alone, or an attitude fixed at a shallow level of understanding. Such approaches cannot touch the deep emotion or resonance of tradition. This is why, she insists, one must go further down just as clear water can only be found by digging deeper into a well.

“Once you descend, there is still pure, abundant water flowing within. That water is alive, and even today it can be drunk. Tradition is the same. When we approach it sincerely, tradition offers us new sensations and fresh resonance.”

Her upcoming sanjo recording is like a single bowl drawn from that well. It is not stagnant water but clear and living. It is not merely the sound of the past, but the breath of tradition reborn through her hands and her heart in this very moment. Jocelyn trusts in the depth of this well and seeks to pass its living water on to the next generation. For her, it is only by drawing from this depth that tradition can continue to flow outward, shared with the world.

Chapter 04.

이수자로서의 사명감을 지키기 위한

Chapter 04.

The Responsibility of an Heir to Tradition

오늘날 가야금은 다양한 변화를 겪고 있다. 25현금과 같은 새로운 시도가 가능했던 것도 그 중심에 변하지 않는 전통이 있었기 때문이다. 조세린 교수는 이를 누구보다 잘 안다. 그래서 그녀가 해야 할 가장 중요한 일은 이수자로서 전통을 보여주고, 그 본래의 울림을 잊히지 않게 하는 것이다. 대중화와 세계화는 그 위에서만 가능하다고 믿기 때문.

그래서 조세린 교수는 오늘의 관객과 나누기 위해 기회가 올 때마다 무대에 서고, 대중 앞에서 강연을 이어간다.

“한국의 젊은 세대가 국악을 외면하는 건 싫어서가 아니라, 좋은 소리를 접할 기회가 부족하기 때문이라고 생각해요. 그런데 저 같은 외국인이 가야금을 연주하면, 국악을 새롭게 바라보게 하는 작은 자극이 될 수 있다고 믿어요. 제가 특별히 잘해서가 아니라, 외국인이 연주하니 귀를 열고 들어주는 것 같아요.”

그녀는 안다. ‘외국인’이라는 이름에 따른 거리감, ‘전통’이라는 말에 깃든 경건함, 그리고 그 사이에서 생겨나는 오해들을. 하지만 조세린 교수는 외국인 최초 가야금 이수자로서 전통의 맥을 이어가는 책임을 일깨우기 위해 끊임없이 노력한다. 스승에게서 배운 것을 충실히 전하면서도, 시대와 청중이 요구하는 무대 위에서 가야금의 목소리를 살아 있게 하려 한다.

Today the gayageum is undergoing many changes. Innovations such as the 25-string gayageum were possible precisely because an unshaken core of tradition remains at the center. Jocelyn understands this better than most. For her, the most important task as an isunja is to embody tradition and keep its original resonance from being forgotten. She believes that only upon this foundation can sharing with the world become possible.

This is why she embraces every opportunity to perform and to lecture, seeking to connect with today’s listeners.

“I don’t think young Koreans avoid traditional music because they dislike it. Rather, they simply lack the chance to encounter good sound. When someone like me, a foreigner, plays the gayageum, I believe it can be a small spark that makes them look at tradition in a new way. Not because I play especially well, but because hearing a foreigner perform seems to open their ears.”

She is fully aware of the distance that comes with the label “foreigner,” the reverence that surrounds the word “tradition,” and the misunderstandings that can arise between the two. Yet as the first foreign isunja of the gayageum, she continues to work tirelessly to awaken the sense of responsibility that comes with inheriting this lineage. By faithfully passing on what she learned from her teachers, while at the same time responding to the demands of the present moment and its audiences, Jocelyn strives to keep the voice of the gayageum alive on stage.

그렇게 조세린 교수는 오늘도 전통의 우물 곁에 서 있다. 25현금이든 즉흥 연주든, 혹은 낯선 이방인의 손끝이든, 어떤 방식으로든 그 물을 길어 올릴 수 있다면 기꺼이 그릇이 되고자 한다. 중요한 것은 형식이 아니라 마음이다. 그녀의 가야금을 향한 진심을 지켜보는 일, 그것이 곧 우리가 전통과 함께 호흡하는 또 다른 방법일 것이다.

Thus, Professor Jocelyn stands today beside the well of tradition. Whether through the 25-string gayageum, through improvisation, or through the hands of a foreigner, she is willing to become the vessel as long as the water can be drawn. What matters is not the form, but the heart. To witness her sincerity toward the gayageum is, in its own way, to breathe together with tradition.

조세린

조세린 교수는 미국 워싱턴 D.C.에서 태어나 알래스카 주 노에서 성장했으며, 하버드대학교에서 동아시아 언어 및 문명으로 석·박사 학위를 받았다. 현재 배재대학교 주시경 교양대학 교수로 재직 중이며, 가야금 산조와 병창 분야에서 외국인 최초로 전라북도 무형문화재 전수자로 인정받았다. 그는 어린 시절부터 음악과 친밀하게 지냈고, 이후 일본의 고토, 중국의 구쟁, 한국의 가야금 등 동양의 전통 악기를 배우며 학문적·예술적 기반을 다졌다. 미국과 일본, 중국을 넘나들며 전통음악과 문화에 대한 연구를 이어왔고, ‘CrossSound 현대음악 축제’를 설립하여 동서양 음악의 융합을 시도했다. 다수의 논문과 연구 결과를 발표하며 학자로서도 활발히 활동하고 있으며, ‘조세린 클라크의 문화산책’ 같은 칼럼을 통해 대중과 소통해 왔다. 국악의 전도자로서 한국 전통음악의 교육과 보급, 대중화를 위해 헌신하고 있으며, 특히 가야금을 매개로 한 문화 교류의 중심에서 활동하고 있다.

Jocelyn

Professor Jocelyn was born in Washington D.C. and grew up in Juneau, Alaska, later earning her M.A. and Ph.D. in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University. She is currently a professor at Pai Chai University’s Jusikyung College of Liberal Arts and is recognized as the first foreigner to be designated a trainee in the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Gayageum Sanjo and Byeongchang in Jeollabuk-do. From an early age she was immersed in music and later studied East Asian instruments such as the Japanese koto, the Chinese guzheng, and the Korean gayageum. She has pursued research on traditional music and culture across the U.S., Japan, and China, and founded the CrossSound New Music Festival to explore fusion between Western and Eastern traditions. Clark has published numerous scholarly articles and engages in public discourse through her column “Cultural Stroll with Jocelyn Clark.” As a cultural ambassador and educator, she continues to dedicate herself to teaching and popularizing Korean traditional music, particularly through the gayageum, while fostering cross-cultural dialogue.

Epilogue

조세린 교수는 가야금 병창을 주제로 하버드대학교에서 박사 논문을 썼다. 단순히 연주에 그치지 않고, 노래 속 언어를 풀어 읽고 역사적 배경을 하나씩 살펴보는 긴 여정이었다. 처음에는 그저 병창을 연주하고 싶었던 그녀는, 자신의 나라 사람들에게 이 소리를 들려주기 위해 가사 번역을 시작했다. 그러다 판소리의 언어와 문화를 하나씩 이해하고 풀어가야 했다.

“판소리는 재미있어요. 서민의 입말과 중국 고전의 언어가 한 곡 안에 함께 있어요. 그런 언어는 흔치 않죠.”

서로 다른 말들이 한 곡 안에서 뒤섞여 흐르는 그 속에서, 그녀는 한국의 정서를 느꼈고 그 감정을 전하고 싶었다. 논문도 자연스럽게 동리 신재효가 어떤 시를 판소리에 담았는지를 분석하고, 당시 유행한 문학을 살피는 연구로 이어졌다.

이번 취재에서 우리는 연주자 조세린뿐 아니라, 연구자 조세린, 그리고 한국을 진심으로 아끼는 한 사람을 만날 수 있었다.

Epilogue

Professor Jocelyn wrote her doctoral dissertation at Harvard University on gayageum byeongchang. It was not only about performance but about the long journey of unfolding the language of the songs and tracing their historical background. At first she simply wanted to perform byeongchang. To share its sound with people in her own country, she began by translating the lyrics. But translation alone was not enough. She had to enter into the language and culture of pansori itself.

“Pansori is fascinating. In a single piece you find the speech of ordinary people intertwined with the language of Chinese classics. That kind of mixture is rare.”

Within these overlapping voices she began to feel the texture of Korean sentiment, and she wanted to convey that emotion. Her dissertation naturally evolved into a study of how Shin Jae-hyo, the nineteenth-century scholar, embedded poetry into pansori and how contemporary literature shaped the art form of its time.

Through this, we came to see not only Jocelyn the performer, but also Jocelyn the scholar—and beyond both, a woman who treasures Korea with sincerity.