서울에서 런던까지, 도시에게 질문을 던지는 사람 – 민준홍

From Seoul to London, Questioning the City - Min Junhong

Localler

새롭게 떠오르는 문화를 발견해 융합해 나가는 ‘문화의 선구자 Culture Vanguard’ 역시 기아 디자인 크리에이티브 철학의 문화적 특징 중 하나입니다. 기아디자인매거진은 Localler라는 메뉴를 통해 ‘문화의 선구자 Culture Vanguard’라는 타이틀로 한국에서 살고 있는 현지 외국인, 외국에서 살고 있는 현지 한국인들의 경계 없는 스토리를 보여줍니다.

Localler

As a Culture Vanguard, who discovers and integrates emerging culture, is another feature of Kia Design’s creative philosophy. In the Localler menu, Kia Design Magazine presents stories about foreigners living in Korea, as well as Koreans living abroad, under the title ‘Culture Vanguard’.

도시에서 살아가는 사람들은, 때때로 자신이 도시 안에 살고 있다는 사실조차 잊곤 한다. 익숙함에 묻힌 거리에서 반복되는 일상 속에서 도시는 그저 배경이 되어버리기 때문이다. 민준홍 작가는 그 틈에서 도시의 숨결을 길어 올린다. 도시를 ‘기억의 지도’처럼 펼쳐놓은 작가는 반복되는 드로잉, 수집된 오브제, 왜곡된 풍경 등으로 도시의 내면을 담는다. 그 내면은 곧 자신이기도 하고, 도시를 살아가는 우리 모두의 얼굴이기도 하다. 작가는 치열한 경쟁 속에서 불안하기도 했지만 행복하기도 했던 30년의 시간을 보낸 서울을, 애증의 공간으로 정의했다. 그 불안했던 감정을 해소하기 위해 펜을 들었고, 그것은 창작의 동기가 되었다. 그의 창작은 런던으로 향하면서 한층 더 확장되었다. 서울과는 또 다른 결을 지닌 런던의 고풍스러운 건축물에 매료된 그는, 학교를 오가며 매일같이 도시를 걷고 유영했다. 시간이 흐를수록 그는 비로소 깨달았다. 풍경은 달라도, 서울과 런던은 ‘도시’라는 점에서 본질적으로 닮아 있다는 것을. 산업혁명의 원류인 런던은 도시의 원형과도 같은 곳이었고, 그는 그곳에서 도시라는 구조가 어떻게 형성되고, 또 작동하는지를 피부로 느낄 수 있었다. 런던에서 거주하고 활동하며, 그 일상의 결을 따라 창작해온 민준홍 작가는 이제 ‘도시’라는 주제를 자신만의 언어로 다시 그려내고 있다. 그의 작업은 런던이라는 구체적 장소성에 뿌리를 두되, 파리, 베를린 등 다른 도시들로 확장되며 도시에서 현대 사회로, 구조에서 인간으로 시선을 넓혀가고 있다. 이제 작가가 작가가 던지는 질문에 도시는 어떤 답을 주는지 그의 이야기를 따라가보자.

People living in cities often forget that they are in fact living within them. As daily life repeats itself along familiar streets, the city fades into the background. Artist Min Junhong draws out the breath of the city from these in-between moments. He unfolds the city like a map of memories, capturing its inner layers through repeated drawings, collected objects, and distorted landscapes. This inner landscape reflects not only himself but also the faces of all who live in the city. He describes Seoul, where he spent thirty years amid intense competition and fleeting happiness, as a place of both love and hate. In an attempt to release the anxiety he felt, he picked up a pen, and that act became the starting point of his creative journey.

His work expanded further when he moved to London. Captivated by the elegant architecture of the city, so distinct from Seoul, he walked through the streets daily, letting himself drift through its textures. Over time, he came to a realization: though the scenery differs, Seoul and London are fundamentally similar in that they are both cities. As the cradle of the Industrial Revolution, London stands as a prototype of urban life. There, he could physically experience how a city is formed and how it functions.

Now based in London, Min continues to create art inspired by the fabric of daily life. His exploration of the city has grown beyond a single place. While rooted in the specificity of London, his work extends to other cities such as Paris and Berlin. Through this expansion, his focus shifts from the city to contemporary society, from urban structure to the human being. Let us follow his journey and see what answers the city offers in response to the questions he poses.

민준홍 작가는 도시를 그릴 때 산책을 하면서 영감을 주는 도시의 모습을 자신의 관점으로 카메라를 담는다.

서울은 그에게 첫 도시였다. 감정의 원형이자, 창작의 기폭제였다. 서울에서 태어나고 자란 민준홍 작가는 입시 경쟁을 겪었고, 대학 진학 후에는 스펙을 쌓기 위해 치열하게 노력해왔다. 그 속에서 그는 내면의 불안을 느꼈고, 그 감정을 드로잉을 통해 해소해 나갔다. 복잡 미묘한 감정을 끊임없이 불러일으키는 서울이라는 공간을 그리다 보니, 그의 작업은 자연스럽게 ‘도시’라는 주제로 확장되었다.

대학 졸업 후 런던으로 건너가, 도시를 바라보는 감각의 지평을 넓히게 된다. 처음에는 시간의 흔적이 쌓인 건축물과 정제된 도시 계획 등은 영감이 되었지만 결국 런던 역시 서울과 크게 다르지 않다는 결론에 도달했다. ‘도시’라는 구조 아래 작동하는 자본주의 시스템, 사람들의 일상, 경쟁과 생존, 그리고 보이지 않는 규범들은 서울과 런던 모두에게 내재된 도시의 본질이었기 때문이다. 자신의 불안한 감정에서 한 발 더 나아가, 동시대를 살아가는 사람들과 동시대의 문화 등을 ‘도시’라는 시대정신을 건네고자 한다. 《기아 디자인 매거진》은 민준홍 작가에게 물었다. 다양한 도시의 모습을 담아내는 그의 작업 속에서 도시의 본질은 무엇이며, 그가 바라보는 현대사회는 어떤 모습인지.

Seoul was his first city. It was the origin of his emotions and the catalyst for his creativity. Born and raised in Seoul, Min Junhong experienced the pressures of competitive entrance exams and, once in university, devoted himself to building a strong portfolio. Amid this intense environment, he began to feel a growing sense of inner anxiety. Drawing became his way of confronting and easing those emotions. As he continued to depict the space of Seoul, a city that constantly stirred complex and delicate feelings, his work naturally expanded toward the broader theme of the city.

After graduating, he moved to London, where his perspective on urban life widened. At first, the city’s aged architecture and carefully planned streets served as sources of inspiration. But eventually, he came to realize that London was not so different from Seoul. Beneath the surface, both cities shared the same essence: capitalist structures, the routines of everyday life, competition and survival, and invisible social norms. Now, moving beyond his personal sense of unease, Min seeks to reflect the spirit of the times, urban existence, shared culture, and the people of today through the language of the city.

The Kia Design Magazine sat down with Min Junhong to ask: What is the essence of the city found in his work, and how does he see the society we live in today?

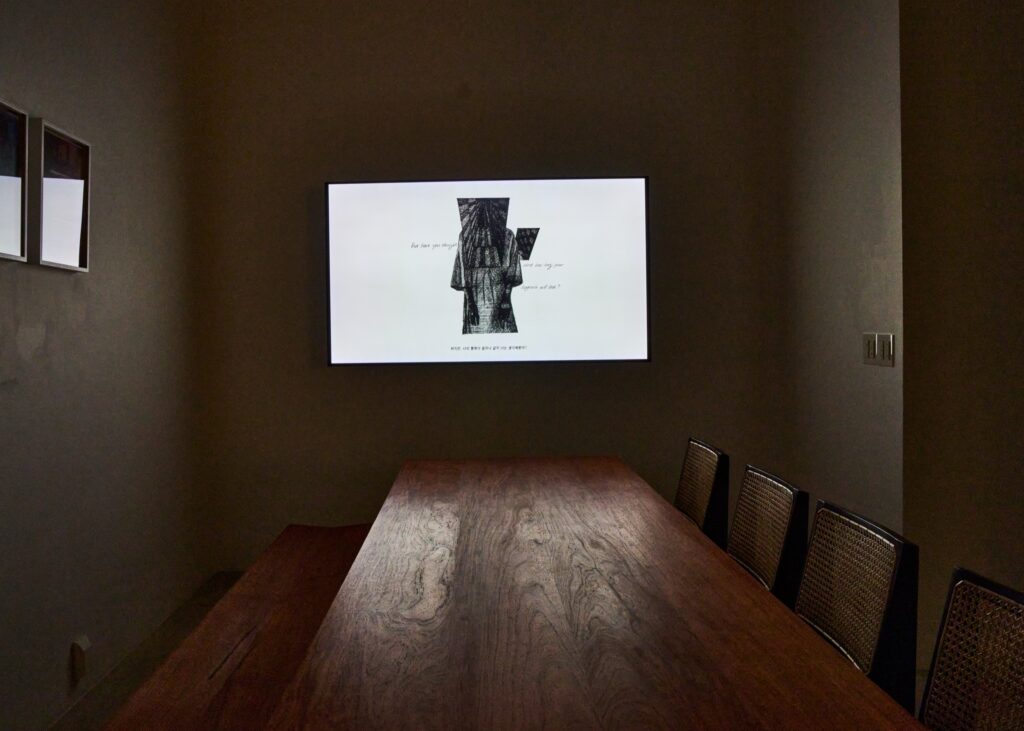

민준홍 작가는 도시라는 공간을 무대로, 한국의 전통 문양과 현대사회의 병폐를 설치 작품과 영상으로 감각적으로 풀어낸다.

#익숙함에서 벗어나야 보이는 것들

#What Becomes Visible Only

When You Step Outside the Familiar

작가는 런던에 오지 않았다면 결코 알지 못했을 감각을 깨달았다.

처음엔 동경하던 런던의 풍경과 문화에 흠뻑 빠졌지만,

시간이 흐르면서 서울과 런던이 생각보다 많이 닮아 있다는 사실에 닿게 되었다.

서로 다른 얼굴을 한 두 도시. 그러나 그 안을 채우는 건 언제나 같았다.

도시란, 결국 같은 시간을 살아가는 사람들이 만들어내는 하나의 얼굴이라는 것을The artist awakened a sense he would never have known had he not come to London.

At first, he was immersed in the scenery and culture of the city he once admired.

But over time, he came to realize that Seoul and London were more alike than they seemed.

Two cities with different faces, yet filled with the same essence.

Because in the end, a city is a collective face shaped by people living through the same time together.

도시를 오브제로 작품 활동을 하고 계신데요. ‘서울’을 그리게 된 이유는 무엇인가요?

서울은 저에게 단순한 고향이나 배경 이상의 공간이에요. 애정과 불안이 동시에 얽혀 있는 도시랄까요. 서울에서 태어나고 자라면서 겪은 입시, 경쟁, 사회적인 압박 같은 것들이 어쩌면 지금까지도 제 감정의 근간에 깊이 남아 있는 것 같아요. 그래서 제 작업은 저의 불안함을 해소하기 위한 시작이었습니다. 계속해서 드로잉을 하게 된 이유가 그것 때문입니다.

You use the city as an object in your work. What made you start depicting Seoul in particular?

Seoul is more than just my hometown or a backdrop. It is a place where affection and anxiety are closely intertwined. Growing up there, I experienced the pressures of entrance exams, constant competition, and social expectations. Those experiences still remain deeply rooted in my emotional foundation. In a way, my artistic practice began as a way to relieve that sense of unease. That is also why I have continued drawing. It helps me work through those lingering emotions.

드로잉이 불안을 해소해주었다고 하셨는데, 어떤 점이 그렇게 다가온 것일까요?

드로잉은 언제나 지금까지도 그래왔고 앞으로도 그럴 것 같은데요. 제가 미술 작업을 하는 데 있어서 언제나 시발점이 되는 것 같아요. 반복적인 드로잉, 펜 선, 반복적인 무언가를 긋는 행위가 저에게는 큰 해소가 되었습니다. 드로잉에 몰입하다 보면 감정적인 동요도 일어나지 않고, 잡념이 생기지 않고요. 재미있는 형상 같은 걸 만들 때 결 결과물보다 과정에 몰입하는 어린아이들의 모습이 제 작업과 닮아 있는 것 같아요.

You mentioned that drawing helped ease your anxiety. What was it about drawing that had that effect on you?

Drawing has always been, and probably always will be, the starting point of my artistic practice. The repetitive act of drawing, the motion of pen lines, and the continual movement of marking something again and again brought me a deep sense of relief. When I am immersed in drawing, I do not feel emotional turmoil or get distracted by stray thoughts. It reminds me of how children get absorbed in the act of making something fun, focusing more on the process than the outcome. I think my work shares that same quality

그 작업이 런던으로 유학을 가시면서 이어지게 되었어요. 런던을 선택하신 이유가 있나요?

사실 저는 런던에 대한 일종의 패티시 같은 것이 있었어요. 일종의 동경 같은 거라고 말할 수 있겠어요. 대중문화를 통해 접했던 런던의 분위기, 날씨, 소설과 영화 속 모습과 런던에서 활동하는 데미안 허스트, 레이첼 와이트리드 같은 작가들, 그들이 전시를 꾸미는 방식, 미술관이나 갤러리, 인스티튜션Institution의 구조 같은 것도 저한테는 참 흥미로웠어요. 무엇보다도 런던은 산업사회와 자본주의 도시 구조의 원형이 만들어진 공간이잖아요. 그래서 도시라는 주제를 다루는 저에게는 꼭 한 번 거쳐야 할 곳이라는 생각이 강하게 들었던 거죠.

Your work continued while studying in London. Was there a reason you chose London in particular?

I think I had a kind of fascination for London, or maybe it was more of a deep longing. I was drawn to the atmosphere I had encountered through pop culture, the weather, the cityscapes found in novels and films, and artists like Damien Hirst and Rachel Whiteread who were active there. I was especially intrigued by the way they curated exhibitions and by the structure of museums, galleries, and institutions in London. More than anything, London is where the foundations of the industrial society and the capitalist urban system were formed. As someone who explores the theme of the city in my work, I strongly felt that London was a place I had to experience firsthand.

런던에서는 어떻게 생활을 하셨나요?

런던에서의 학업 기간은 약 2년 정도였습니다. 그 시간 동안 저는 영국뿐 아니라 주변 유럽 국가의 갤러리와 미술관을 최대한 많이 찾아다니려 했습니다. 대부분의 기관들이 무료로 개방되어 있어, 당시 유럽 미술계의 흐름을 보다 폭넓고 편견 없이 마주할 수 있었던 소중한 경험이었습니다. 제가 다녔던 유니버시티 칼리지 런던(University College London)의 슬레이드 스쿨 오브 파인 아트(SLADE School of Fine Art)에서는 자체 경연이나 전시 응모가 자주 열렸고, 런던에서 유학 중인 학생들을 대상으로 한 다양한 전시에 적극적으로 지원서를 제출하며 참여했던 것으로 기억합니다. 학교 수업만으로는 런던 미술계의 현장을 체감하기 어렵다고 느껴, 같은 학과 친구들과 함께 직접 전시를 기획하고 공간을 조성한 경험도 있습니다. 그 시간들은 단순히 배우는 것을 넘어, 현장 속에서 스스로 움직이고 연결되었던 의미 있는 시간이었습니다.

What was life like for you in London?

I spent about two years studying in London. During that time, I tried to visit as many galleries and museums as possible, not only in the UK but also in neighboring European countries. Since most institutions were open to the public free of charge, it was a valuable opportunity to encounter the European art scene more broadly and without bias. At the Slade School of Fine Art at University College London, where I studied, there were frequent competitions and open calls for exhibitions. I actively submitted my work and participated in various shows aimed at international students in London. I also felt that attending classes alone was not enough to truly experience the local art scene, so I worked with classmates to organize our own exhibitions and create exhibition spaces from scratch. Those moments were meaningful not just as learning experiences, but as opportunities to take initiative and connect directly with the field.

여러 경험을 하신 만큼 런던이라는 도시에서 서울과는 다른 점은 없었나요?

처음엔 당연히 아주 많이 다르다고 느꼈어요. 런던은 건물이나 거리 곳곳에 시간이 켜켜이 쌓여 있는 듯했고, 도시 전체가 훨씬 더 정제된 계획 속에서 조용히 움직이는 느낌이었거든요. 날씨나 공기, 도시의 리듬도 서울과는 사뭇 달랐고요. 그런데 시간이 지나면서 조금씩 생각이 달라졌어요. 겉모습은 다르지만, 도시라는 구조 안에서 돌아가는 자본주의 시스템이나 경쟁, 규범, 생존 방식은 결국 서울과 런던 모두에게 비슷하게 작용하고 있다는 걸 느꼈거든요. 오히려 저는, 서울에서 익숙하게 보아왔던 도시의 원형을 런던에서 더 선명하게 마주한 기분이었어요. 그래서 지금은 ‘다르다’기보다는 ‘닮아 있다’는 말이 더 마음에 와닿아요.

Having had so many experiences, did you find any differences between London and Seoul as cities?

At first, I thought they were very different. In London, it felt as though layers of time were embedded in every building and street. The entire city moved quietly within a more carefully structured plan. The weather, the air, and the rhythm of life were also quite different from those in Seoul. But as time passed, my thoughts began to change. Although the outward appearances differed, I realized that the inner workings of the city — capitalism, competition, social norms, and survival — functioned similarly in both places. In fact, it felt like I was seeing the original form of the city, which I had always been familiar with in Seoul, even more clearly in London. So now, rather than saying they are different, I find it more fitting to say that they are alike.

런던에서 활동하지 않았다면 절대 깨닫지 못했을 수도 있을 것 같아요.

맞아요. 이곳에서 머물며 도시라는 공간을 더 깊이 들여다보게 되었고, 결국 서울과 본질적으로 다르지 않다는 사실에 닿게 되었어요. 낯선 도시에서 익숙함을 되짚는 동안, 오히려 서울에서 미처 보지 못했던 것들이 서서히 시야에 들어오기 시작했죠. 팬데믹 이후 서울로 돌아왔을 때, 예전처럼 높이 솟은 건물들보다는 그 틈새에 자리한 오래된 풍경들 한국의 전통적인 공간과 조형 요소들이 새롭게 다마음에 들어왔어요. 그렇게 시선이 바뀌니, 서울이라는 공간이 제가 말을 걸어왔고, 자연스레 지난 4월에 한국에서 연 전시《Nevertheless, the windmill runs | 그럼에도, 풍차는 돌아간다》의 작품 속에 한국 전통 문양 등이 스며들었죠.

It sounds like these are insights you might never have had without your time in London.

That is true. Living here allowed me to look more deeply into the nature of cities, and I eventually came to realize that Seoul is not fundamentally different. While revisiting what was familiar in an unfamiliar place, I began to notice things about Seoul that I had previously overlooked. When I returned to Seoul after the pandemic, it was not the tall buildings that caught my eye, but the older scenes tucked between them. Traditional Korean spaces and design elements began to speak to me in a new way. With that shift in perspective, Seoul felt as if it was reaching out to me, and naturally, those elements found their way into the works I presented in my exhibition last April in Korea, titled “Nevertheless, the Windmill Runs.” Korean traditional patterns became gently embedded in the pieces.

그렇다면, 도시 안에서 살아가는 사람도 본질적으로 닮아 있다고 생각하시는 걸까요?

저는 파리, 베를린, 뉴욕 등지에서 다양한 레지던시에 참여하며 작품 활동을 이어왔습니다. 2020년 NARS Foundation에서는 세계 각국의 작가들과 3개월간 스튜디오를 공유했고, 그룹전 《The Process of Calculating One’s Position》을 통해 각자의 시선이 반영된 작업들을 선보였습니다. 서로 다른 배경 속에서도 유사한 생각과 조건들이 교차하고 있다는 공감은 이후 작업의 중요한 기반이 되었고, 도시 문명과 정보의 범람을 다루는 제 작업이 보다 자연스럽게 받아들여질 수 있는 배경이 되었다고 생각합니다. 이런 경험들이 저의 시선을 더욱 단단하게 만들고, 작업을 지속할 수 있는 원동력이 되고 있습니다.

Then, do you believe that people living in cities are fundamentally similar as well?

I have continued my practice by participating in various residencies in cities like Paris, Berlin, and New York. In 2020, I spent three months sharing a studio with artists from around the world at the NARS Foundation, where we presented our work in a group exhibition titled “The Process of Calculating One’s Position.” Through that experience, I felt a strong sense of connection as I realized that similar thoughts and conditions can emerge even among people from very different backgrounds. That sense of shared understanding became an important foundation for my later work. I believe it also helped create a context in which my practice, which deals with urban civilization and the overflow of information, could be received more naturally. These experiences have sharpened my perspective and continue to give me the energy to sustain my work.

#관점의 확장

#Expanding Perspectives

서울을 시작으로 런던, 파리, 베를린을 거치며 작가는

도시를 바라보는 시선을 깊게 다져갔다.

자본주의 시스템과 물질주의적 속성에 대한 인식은 점차 뚜렷해졌고,

그 여정 중 팬데믹이라는 특수한 시대를 맞이하게 된다.

도시가 멈춘 그 시기, 작가는 오히려 가상 공간에서 새로운 감각을 발견했고,

현실의 도시와 디지털 세계를 병치시키며 현대 사회의 단면을 담기 시작했다.Starting in Seoul and moving through London, Paris, and Berlin, the artist gradually deepened his perspective on the city. His awareness of capitalist systems and materialistic tendencies became increasingly clear, and along the way, he encountered the unique era of the pandemic. During that time, when cities came to a standstill, he instead discovered a new kind of sensitivity within virtual spaces. By juxtaposing the physical city with the digital realm, he began to capture revealing fragments of contemporary society.

그렇다면 런던에서 생활하시면서 작가님의 작품의 변화가 있었을까요?

예전에는 서울이라는 공간 안에서 느껴지는 불안감을 달래기 위해 반복적으로 드로잉을 하거나, 도시 공간이라는 구조적인 형태를 만들고 그것을 하나씩 채워나가는 식의 작업을 했었는데요. 그런데 이곳, 런던으로 오면서부터는 주변에서 실제로 발견할 수 있는 소품이나 공간, 그리고 이미지들이 제 작업을 채워가기 시작했어요. 런던의 교통비가 비싼 덕분이기도 한데요. 영국 집에서 스튜디오까지 걸어가면서 보이는 건축폐기물이나 자재를 가져와 작품 속에 녹여내는 방식으로 변화했어요.

Then did your time in London bring any changes to your artistic practice?

In the past, I used to draw repetitively to ease the sense of anxiety I felt within the space of Seoul, or I would construct structural forms based on the city and gradually fill them in. But after coming to London, my work began to incorporate actual objects, spaces, and images I encountered around me. In a way, it was also thanks to the high cost of transportation in London. I often walked from my house to the studio, and along the way, I would collect discarded construction materials or architectural debris, which then became part of my work.

베를린, 파리 등에서도 작업을 하셨어요. 도시라는 공통점이 있지만 다른 관점에서 바라보게 된 점도 있을 것 같아요?

네, 도시라는 큰 틀에서는 공통점이 있지만, 각각의 도시가 품고 있는 시간성과 분위기, 구조 자체가 너무 달라서 저도 자연스럽게 다른 시선으로 접근하게 되더라고요. 예를 들어 베를린은 비교적 최근에 통일된 도시라, 동서의 분단과 통합의 흔적들이 여전히 곳곳에 남아 있어요. 짧은 거리 안에서도 전혀 다른 시대의 흔적과 분위기를 경험할 수 있었고, 구시대의 건물 안에 힙한 클럽이나 현대미술 갤러리가 공존하는 모습이 굉장히 인상 깊었습니다. 반면 파리는 굉장히 계획적으로 설계된 도시라 겉은 굉장히 아름답고 정제되어 있는데, 그 이면에는 수십 년간 손보지 못한 낡은 내부가 그대로 있는 경우도 많았어요. 외관의 화려함과 내부의 허름함 사이의 간극이 시각적으로도, 감정적으로도 묘한 대비를 만들어냈죠. 이렇게 도시의 구조나 과거가 어떻게 현재에 스며들어 있는지를 바라보는 방식이 자연스럽게 달라지더라고요.

You also worked in cities like Berlin and Paris. While they share the concept of being urban spaces, did they offer you new perspectives?

Yes, while they all fall under the broad framework of a city, each one carries its own sense of time, atmosphere, and structure. That naturally led me to approach them with different perspectives.

For example, Berlin is a city that was reunified relatively recently, so traces of division and integration between East and West are still visible throughout the city. Within a short walking distance, you can encounter very different eras and moods. I was particularly struck by the way trendy clubs and contemporary art galleries coexist within buildings from past decades. Paris, on the other hand, is a city that was very deliberately planned. On the surface, it is refined and beautiful, but often the interiors are quite old and untouched for decades. The contrast between the polished exterior and the worn interior created a fascinating visual and emotional tension. These experiences made me more aware of how the structure and past of a city are embedded in the present, and naturally, my way of observing each city began to change.

여러 나라의 다른 도시의 모습이 작품에 어떤 영향을 미쳤나요?

돌이켜보면 런던, 파리, 베를린 등지에서의 활동 자체보다, 그곳들에서 팬데믹 시기를 겪으며 제 작업이 한층 확장된 것 같습니다. 저는 평소 각 도시의 기반 시설, 건축물, 도시 구조 등에서 영감을 받아 시각적 표현을 구성해왔고, 이것이 제 작업의 출발점이었습니다. 그러나 팬데믹 기간 동안 유럽 대부분의 도시가 셧다운되면서, 물리적 공간을 경험하는 대신 반강제적으로 인터넷이나 OTT 등의 가상 공간을 탐험하게 되었습니다. 그 안에서 마주한 무한한 이미지와 영상들은, 기존의 도시적 감각 위에 덧입혀지며 새로운 층위를 형성하게 되었죠. 만약 그 시기에 한국에 있었다면, 비교적 자유로운 외부 활동 덕분에 물리적 도시 공간에만 집중했을 것이고, 그만큼 가상 이미지가 제 작업 안에 깊이 들어올 기회는 없었을지도 모릅니다. 결국 영미권이나 유럽 도시에서 직접 마주한 자본주의 시스템과, 그 위에 구축된 물리적 도시 공간은 제 도시 인식에 결정적인 확장을 가져왔고, 팬데믹이라는 특수한 상황은 현실의 도시와 가상의 세계를 병치시키는 새로운 작업 방식을 열어주었습니다.

How did the different cities you visited influence your work?

Looking back, it was not just the time I spent in cities like London, Paris, or Berlin that shaped my work, but rather the experience of going through the pandemic in those places that truly expanded it. I have always drawn inspiration from a city’s infrastructure, architecture, and spatial structure, using them as starting points for visual expression. However, during the pandemic, as most European cities went into shutdown, I was forced to explore digital environments like the internet and streaming platforms instead of engaging with physical space. The endless stream of images and videos I encountered there began to layer themselves onto my existing urban sensibilities, creating entirely new dimensions in my work. If I had been in Korea during that period, where movement was relatively less restricted, I might have remained focused on physical urban space and never had the opportunity to deeply incorporate virtual imagery into my work. Ultimately, the capitalist systems I experienced firsthand in Western cities, and the built environments that embody them, led to a significant expansion in my understanding of the urban. The pandemic, as a unique circumstance, opened up a new way of working — one that juxtaposes the physical city with the virtual world.

방식이 달라진 만큼 작품 속 이야기도 변화가 있었을 것 같아요. 과거에는 도시에서 느낀 불안을 이야기하셨는데, 지금은 도시를 어떻게 바라보고 계신가요?

네, 과거에는 도시 속에서 느끼는 개인적인 불안이 작업의 출발점이었다면, 지금은 그 감정이 점차 확장되어 ‘현대인’이라는 더 넓은 존재에 닿아가고 있는 것 같아요. 우리가 살아가는 지금 이 시대는, 정보가 과잉되고 감각이 마모되는 시대라고 생각합니다. 인터넷 속에서 끝없이 소비되는 이미지들, 사라져가는 인문학적 감수성, 그리고 그 모든 것을 지배하는 자본주의적 속성과 물질주의 등 이런 것들이 도시라는 구조 속에 고스란히 스며들어 있죠. 그래서 저는 도시를 하나의 ‘시대적 풍경’으로 보고, 그 안에 내재된 구조를 시각적으로 해석하고 질문하는 작업을 하고 있어요. 어떻게 보면, 도시라는 구체적인 장면을 통해 현대사회를 구상화하는 동시에, 그것을 추상화하는 과정이기도 합니다. 결국 제 작업은 도시에 대한 사적 감정에서 출발해, 동시대를 살아가는 우리 모두의 감각과 구조에 닿고자 하는 여정인 셈이죠.

As your methods have evolved, it seems the narrative within your work has changed as well. In the past, you spoke about anxiety within the city. How do you view the city now?

In the past, personal anxiety I experienced within the city was the starting point of my work. But now, I feel that emotion has gradually expanded toward a broader reflection on what it means to be a modern individual. I believe we live in a time of excessive information and dulled senses. The endless images consumed on the internet, the fading of humanistic sensitivity, and the dominance of capitalism and materialism are all deeply embedded in the structure of the city. That is why I see the city as a kind of landscape of our era. My work focuses on visually interpreting and questioning the systems that lie within it. In a way, I am both visualizing contemporary society through specific urban scenes and abstracting those scenes at the same time. Ultimately, my practice has grown from a personal emotional response to the city into a journey that seeks to connect with the shared sensibilities and structures of our time.

#강렬한 자극제

#A Powerful Stimulus

해외에서의 활동은 민준홍 작가에게 강렬한 ‘자극제’로 작용한다.

자신의 작품에 대한 해석을 관객들이 기꺼이 공유하고,

그것을 아티스트와 자연스럽게 소통하는 문화 속에서

그는 예상치 못한 희열과 마주하기 때문이다.

그래서 민준홍 작가는 자신의 작품에 마침표를 찍기보다,

언제나 물음표 하나를 남겨두고자 한다.Working abroad has served as a powerful stimulus for Min Junhong.

In cultures where audiences are willing to share their interpretations of his work and engage in open dialogue with the artist, he encounters moments of unexpected joy.

That is why he prefers not to place a period at the end of his work. Instead, he always chooses to leave a question mark.

서울처럼 다른 도시에서도 생활했다면 익숙해지기 마련인데, 작가님은 굉장히 도시를 관찰하는 능력이 탁월하신 것 같아요.

저 같은 경우 새로운 도시를 처음 마주했을 때는 진짜 모든 센서가 열리는 느낌이 들어요. 약간 여행자처럼, 조금은 낯선 상태로 도시를 걷다 보면 그 도시에서만 마주할 수 있는 풍경이나 구조, 우연적인 장면들이 시각적으로 확 들어오거든요. 그럴 때는 정말 별것 아닌 구조물이나 사소한 골목도 되게 흥미롭게 다가오고, 계속 사진을 찍죠. 그러니까 ‘왜 이 도시는 이런 느낌이지?’, ‘이 질감은 어디서 오는 거지?’ 그런 질문들을 스스로 던지며 도시를 관찰하고, 걷습니다.

Living in cities like Seoul, one might easily grow used to the surroundings, but you seem to observe urban spaces with remarkable sensitivity.

For me, encountering a new city feels like all my senses suddenly switch on. Almost like a traveler, I walk through the city in a slightly unfamiliar state, and in that mindset, I begin to notice visual elements unique to that place, such as its structures, layouts, and accidental moments. Even the most ordinary alley or small structure becomes incredibly intriguing, and I find myself constantly taking photos. I start asking myself questions like, “Why does this city feel this way?” or “Where is this texture coming from?” That is how I observe a city, by walking, questioning, and paying attention to its details.

관찰자로서 도시라는 공간을 바라보는 작가님의 관점, 혹은 관계성이 궁금합니다.

저에게 ‘관찰자’란 단순히 바라보는 사람이 아니라, 끊임없이 감각하고 질문을 던지는 사람이라고 생각해요. 예를 들어, 도시 안에서 받는 어떤 시각적 충격이나 불안감 같은 건 작업 속 선이나 구조를 더 복잡하게 꼬이게 만들기도 해요. 색감도 마찬가지죠. 다채롭지만 톤이 한껏 눌려 있다든가, 겉으로는 화려해 보이지만 실은 하나의 흐름으로 연결돼 있다든가, 이런 식으로요. 그렇게 반복적으로 쌓이는 드로잉 위에 옷을 입히듯 표현을 더해가는 과정이 저에게는 도시를 읽는 방식이고, 또 기록하는 방식이에요. 예상치 못했던 어떤 ‘마침’의 순간, 뜻밖의 조합 같은 것들을 발견할 때면 기록을 하게 되는 것 같습니다.

As an observer, how would you describe your perspective on the city and your relationship to it?

To me, being an observer is not just about looking. It is about constantly sensing and questioning. For example, a visual shock or a subtle sense of anxiety I feel in the city can make the lines or structures in my work become more entangled and complex. The same goes for color. It may seem vibrant at first, but the tones are often subdued, or what appears colorful on the surface is actually tied together in a single underlying flow. Adding expression on top of layered, repetitive drawings is my way of reading the city and also my way of recording it. When I come across a moment of unexpected resolution or a surprising combination, I feel the need to document it.

작가님의 관점으로 바라본 도시를 ‘질문’이라는 매개체로 이야기하셨습니다. 작가님이 생각하는 예술이란 무엇인가요?

저는 예술은 어떤 완결이 있고 정답이 있는 분야는 아니라고 생각합니다. 작가는 정답을 주는 사람이 아니라, 오히려 질문을 던지는 사람이라고 믿기 때문이죠. 그래서 저는 제 질문을 담은 작품을 관객들도 각자의 방식으로 해석하고 자신만의 경험으로 작품을 마주해주길 바라죠. 전시장을 그냥 산책하듯이 들어왔다가 작품 안에서 자기 인생의 어떤 장면이 떠오른 다거나, 혹은 도시의 구조 속에서 자신이 느꼈던 감정들이 환기되었으면 합니다.

You often describe the city through the lens of questions. In your view, what is art?

I do not believe that art is something that offers clear conclusions or fixed answers. I see the artist not as someone who provides answers, but as someone who asks questions. That is why I hope my works, which contain my own questions, will be interpreted by viewers in their own ways and connected to their personal experiences. I want people to enter the exhibition space as if they are taking a casual walk, and perhaps be reminded of a moment from their own lives. Or maybe the structure of the city in my work will bring back emotions they once felt. That kind of personal engagement is what I hope art can invite.

다양한 방식으로 작품을 전달하시는 이유가 관객과의 소통을 위해서일까요?

꼭 그렇지는 않습니다. 저는 2025년을 살아가는 사람이자, 동시에 작가이기에 무언가를 표현하고 싶을 때는 온몸이 반응해야 한다고 느껴요. 작업을 하다 보면, 어떤 감정이나 생각이 더 이상 드로잉이라는 형식에만 머물 수 없을 때가 있어요. 공간과 호흡하고 싶다거나, 감각적으로 더 직접적인 반응을 원할 때는 자연스럽게 영상이든 설치든, 혹은 퍼포먼스 같은 다른 매체로 확장되곤 하죠. 그래서 어떤 특별한 기준을 가지고 작업 방식을 선택하기 보다는, 그 감정이 어디까지 뻗어나가고 싶은지를 따라가는 편이에요. 저는 작업에 있어 다양성을 중요하게 생각하고, 그 안에서의 융통성을 굉장히 열려 있는 태도로 받아들이고 있어요.

Do you use various mediums in your work as a way to communicate with your audience?

Not necessarily. I see myself as a person living in the year 2025, and also as an artist. When I want to express something, I feel that my whole body needs to respond. Sometimes, while working, a certain emotion or thought can no longer stay within the boundaries of drawing alone. When I feel the need to interact with space, or to evoke a more direct sensory reaction, my work naturally expands into other media such as video, installation, or even performance. So rather than choosing a medium based on a specific rule, I tend to follow the emotion and see how far it wants to reach. For me, diversity in artistic practice is very important, and I try to remain open and flexible in how I approach it.

작가님에게 본질, 소통, 다양성 등의 키워드가 있습니다. 이러한 부분은 해외에서 활동하시면 영향을 받으신 부분 인가요?

그럴 수 있을 것 같아요. 물론 제 성향도 영향을 미쳤겠지만, 해외에서 작품을 선보일 때면 한국 관객과는 확연히 다른 반응을 마주하게 됩니다. 예를 들어, 한국 관객들은 작가가 말하고자 하는 바의 ‘정답’을 찾아내려는 경향이 있다면, 해외 관람객들은 자신이 느낀 감상과 해석을 자유롭게 이야기하고, 그것을 작가에게 거리낌 없이 공유하곤 하죠. 일례로 제가 2022년 파리의 Carrousel Du Louvre에서 《Liquid Purgatory》 전시를 열었을 때인데요. 한 프랑스 중년 관람객이 다가와 이렇게 말하셨죠. “당신의 작품은 계속 보고 있으면 현기증이 나는 것 같아요. 어릴 적 놀이공원에서 탔던 놀이기구가 떠오르네요. 아주 나쁜 기억이었죠. 이 작품도 그래요.” 처음엔 제 작업이 ‘현기증을 유발한다’는 말이 부정적으로 느껴졌고, 솔직히 당황스러웠어요. 그런데 곱씹어 보니, 오히려 지금 시대의 불안정한 감각이나 뒤흔들리는 감정을 제 나름의 방식으로 표현한 결과가 누군가에겐 그렇게 다가갈 수도 있겠다는 생각이 들더군요. 그 자체로도 제 작업의 감상 방식이자, 표현의 한 방식일 수 있다고 받아들이게 되었습니다.

Keywords like essence, communication, and diversity seem important in your work. Do you think these ideas were influenced by your experiences abroad?

I think so. While my own personality certainly plays a role, showing my work abroad has exposed me to reactions that are quite different from those I receive in Korea. For example, Korean audiences often try to find the “right” answer to what the artist is trying to say, whereas international viewers tend to freely express their own interpretations and emotions. They share their thoughts without hesitation, which can be both surprising and refreshing.

I remember one such moment from my 2022 exhibition “Liquid Purgatory” at Carrousel du Louvre in Paris. A middle-aged French visitor approached me and said, “Looking at your work makes me feel dizzy. It reminds me of a ride I took as a child at an amusement park. It was a terrible memory. Your work feels like that.” At first, I felt confused and even a little taken aback. The idea that my work could cause dizziness sounded negative. But as I reflected on it, I began to see it differently. Perhaps the way I express a sense of unease or emotional instability in today’s world resonated with that person’s experience. And in that sense, even discomfort can be a valid and meaningful way of engaging with art.

한국에서 경험하지 못한 자극을 열린 태도로 잘 받아들이시는 것 같아요. 함께 작업하는 사람들도 자극제가 될 것 같아요.

해외에서 미술 관계자들과 함께 작업할 때는, 미술가 또한 전시팀의 일원으로서 수평적인 관계에서 함께 일하는 경우가 많습니다. 그래서 저 역시 전시를 준비할 때, 단순히 작가로서 참여하는 것이 아니라 설치나 홍보 팀의 구성원처럼 직접 작품을 설치하고, 담당 큐레이터와 전시 방향을 조율하는 과정에 적극적으로 관여하곤 합니다. 가끔은 의견이 맞지 않아 얼굴을 붉히는 일도 있었지만, 결국엔 서로 좋은 전시를 만들기 위한 과정에서 생기는 자연스러운 갈등이었고, 전시가 무사히 오픈된 후에는 대부분 만족스러운 결과로 이어졌습니다.

It seems you embrace stimuli you might not encounter in Korea with an open mind. Do the people you work with also become sources of inspiration?

Definitely. When working with people in the art field abroad, artists are often considered part of the exhibition team and treated as equals. In that context, I do not just participate as an artist. I take on roles similar to those of the installation or publicity teams, helping to physically install the work and actively coordinating the direction of the exhibition with the curator. Of course, there were times when we disagreed and even raised our voices, but in the end, those conflicts were part of the natural process of creating a better exhibition together. And once the show successfully opened, those moments usually turned into rewarding experiences.

한국과는 다른 분위기일 것 같아요. 어떤 점에서 차이가 있나요?

한국에서는 제가 많은 분들과 작업해본 것은 아니지만, 작가의 의도와 구상을 최대한 존중하고 전적으로 지원해주시려는 경우가 많았어요. 긍정적인 측면에서 보면, 작가로서의 역량을 신뢰해주시고 창작에 집중할 수 있도록 배려해주시는 것이라 감사하게 생각합니다. 하지만 때로는, 내가 과연 잘하고 있는 걸까, 혹은 너무 독단적으로 움직이고 있는 건 아닐까 하는 의구심이 들기도 하죠. 저는 예술가이지만, 커뮤니케이션을 매우 중요하게 생각하는 사람이에요. 그래서 서로를 프로젝트의 ‘파트너’로 인식하며 함께 만들어가는 전시를 했으면 해요.

It sounds like the atmosphere abroad is quite different from Korea. In what ways do they differ?

Although I have not worked with many people in Korea, my experience has been that most collaborators try to fully respect and support the artist’s vision. In a positive sense, I appreciate that they trust my capabilities and give me the space to focus on the creative process. But at times, it also makes me wonder — am I really on the right track? Am I being too self-directed? These questions come up. As an artist, I place a lot of value on communication. I hope for exhibitions where everyone involved sees each other as partners in the project, building it together through shared dialogue and collaboration.

한국에서 흔하지 않는 개념인 예술 분야에 있어 기업가정신도 그러한 영향일까요?

네, 맞아요. 저도 외국에서 활동하면서 그 생각이 더 명확해진 것 같아요. 해외의 전업 작가들을 보면, 정말 실용적이고 전략적으로 작업을 바라보는 태도가 분명히 있거든요. 그게 속물적이라는 말은 아니고요. 작가도 결국 생계를 유지해야 하는 직업인이잖아요. 저도 작업을 통해 먹고 살아야 하고, 내가 원하는 작업을 지속하기 위해서는 매출도 신경 써야 하고, 내 작업이 어떻게 매력적으로 보일지도 고민해야 하는 거죠. 그렇기 때문에 저는 예술가로서도 일정 부분 기업가 정신이 필요하다고 생각해요.

Do you think the idea of entrepreneurship in the arts, which is still relatively uncommon in Korea, was also shaped by your experiences abroad?

Yes, absolutely. I think my experiences overseas helped clarify that perspective. Many full-time artists abroad approach their work with a clear sense of practicality and strategy. That does not mean they are being materialistic. After all, being an artist is also a profession, and we have to make a living through our work.I need to earn an income to continue creating the kind of work I want, and that means I have to think about sales and how my work is perceived by others. In that sense, I believe a certain level of entrepreneurial mindset is essential, even for artists.

그렇다면 작가님을 사업가로 어느 정도 단계에 와 있는 것일까요?

이제 시작인 것 같아요. 몇 년 전까지만 해도 투잡을 병행하며 작업했거든요. 통역도 하고, 식당 직원(웨이터) 일도 했고, 갤러리에서 테크니션으로 일하며 설치를 도운 적도 있어요. 다행히 최근 몇 년 사이에는 작품 활동만으로 작업을 이어가고 있어서, 조금씩 ‘자영업자’로서의 작가 삶을 진짜로 시작하고 있는 단계라고 생각해요. 요즘 말로 하면 저도 자영업자인데, 전 세계적으로 자영업자들이 위기잖아요. (웃음) 그래서 늘 긴장 속에서 작업을 이어가고, 다음을 준비하고 있는 중이에요.

Then where would you say you are now in terms of being an artist with an entrepreneurial mindset?

I feel like I am just getting started. Until a few years ago, I was juggling multiple jobs while making art. I worked as an interpreter, waited tables at a restaurant, and even assisted with exhibition installations as a technician at a gallery. Thankfully, in recent years I have been able to focus solely on my art, so I think I am finally beginning to live the life of a self-employed artist. In today’s terms, I am a freelancer or small business owner, and as we all know, self-employed people are facing tough times everywhere. (Laughs) That is why I continue to work with a sense of tension and stay prepared for whatever comes next.

투잡을 그만하시고 본격적으로 활동 영역을 넓히고 계시는데요. 앞으로의 방향에 대해 이야기해주세요.

지금은 ‘작품만으로’ 작업을 이어가는 단계에 막 진입한 시기예요. 더 집중해서, 제 작업의 영역을 넓혀가고 싶다는 생각이 강하게 들어요. 구체적으로는, 어떤 건물의 외관이나 실제 공간 전체를 덮는 설치 작업을 해보고 싶어요. 공간 자체가 하나의 감각 구조처럼 느껴지는, 그 안에 들어섰을 때 관객이 마치 ‘작품 안에 들어와 있는 듯한’ 경험을 할 수 있는 작업을 상상하고 있어요. 개인적으로는, 내러티브가 담긴 퍼포먼스 작업도 꼭 한번 시도해보고 싶어요. 아직은 그 형태가 정확히 그려진 건 아니지만, 제 그림 속 인물들이 뭔가를 쓰고 있거나, 저 자신이 그 인물처럼 실제로 무엇인가를 몸에 걸친 채 공간을 이동해보는 퍼포먼스를 구상 중이에요.

You have moved on from juggling side jobs and are now fully focused on your art. Could you share a bit about the direction you hope to take going forward?

Right now, I feel like I have just entered the phase where I can truly sustain my practice through my artwork alone. This has made me even more eager to focus deeply and expand the scope of what I do. Specifically, I am interested in creating large-scale installations that cover the exterior of a building or transform an entire physical space. I want to produce a kind of sensory structure where viewers feel as if they are stepping inside the artwork itself. On a more personal level, I also want to explore performance work that involves narrative. The idea is still in the early stages, but I imagine a performance where the figures in my drawings appear to be writing something, or perhaps I take on their role by wearing certain objects or garments and moving through a space. It is a concept I am continuing to develop.

마지막으로 아직 가야할 길이 많으시지만 어떤 아티스트로 남고 싶은가요?

가끔은 ‘마지막 순간’을 상상하게 돼요. 어디서 죽는지는 중요하지 않지만, 사랑하는 사람이 곁에 있고, 가능하다면 ‘다음 전시를 준비하면서’ 떠날 수 있다면 가장 이상적일 것 같아요. 작업은 제게 취미이자 직업이고, 여가이자 고문이에요. 작가로 산다는 건 많은 걸 경험하면서도 동시에 많은 걸 포기하는 삶이기도 하죠. 그래서 언젠가 이 길을 완전히 내려놓는 걸 상상하면, 어쩐지 허무할 것 같아요. 오히려 그 마지막 순간까지도 ‘다음’을 준비하고 있는 현재진행형의 작가로 남아 있고 싶어요.

Lastly, though you still have a long journey ahead, what kind of artist would you like to be remembered as?

Sometimes, I imagine my final moment. It does not really matter where I die, but if someone I love is by my side, and if possible, I could leave this world while preparing for my next exhibition, that would feel ideal. Art is both a hobby and a profession for me. It is leisure and labor at the same time. Living as an artist means experiencing a lot, but also giving up a lot along the way. That is why the idea of completely letting go someday feels strangely empty. Instead, I want to remain an artist who is always in motion, someone who is still preparing for what comes next, even in the very last moment.

About 민준홍

서울에서 태어난 민준홍(1984년생)은 서울대학교 미술대학 회화과 및 동 대학원을 졸업한 후, 런던의 UCL 슬레이드 예술대학에서 석사 학위를 취득하며 국제적인 예술적 기반을 확립했다. 도시 공간과 건축 구조물에서 영감을 받은 그의 예술은, 현대 사회의 불안과 소비주의를 탐구하는 강렬한 반추상적 언어로 표현된다. 민준홍 작가는 사치 갤러리Saatchi Gallery, 영은미술관, 런던 필드 프로젝트 스페이스, 저우드 스페이스Jerwood Space 등 주요 미술 기관에서 그의 작품이 소개되었으며, 런던, 서울, 뉴욕 등 국제적 도시를 무대로 활발한 활동을 펼치고 있다. 그의 작품은 사치 콜렉션Saatchi Collection을 비롯한 여러 기관과 개인 소장가들에게 소장되며, 현대 미술계에서 독보적인 입지를 구축하고 있다.

About Min Junhong

Born in Seoul in 1984, Min Junhong earned both his BFA and MFA in Painting from Seoul National University before completing his MA at the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London. Through this path, he established a strong international foundation for his artistic practice. Inspired by urban spaces and architectural structures, Min’s work explores themes of anxiety and consumerism in contemporary society through a bold, semi-abstract visual language. His art has been exhibited at major institutions including Saatchi Gallery, Young Eun Museum of Contemporary Art, Field Project Space in London, and Jerwood Space. Actively working across global cities such as London, Seoul, and New York, Min Junhong’s work is part of the Saatchi Collection and numerous other institutional and private collections. He continues to build a distinctive presence in the field of contemporary art.